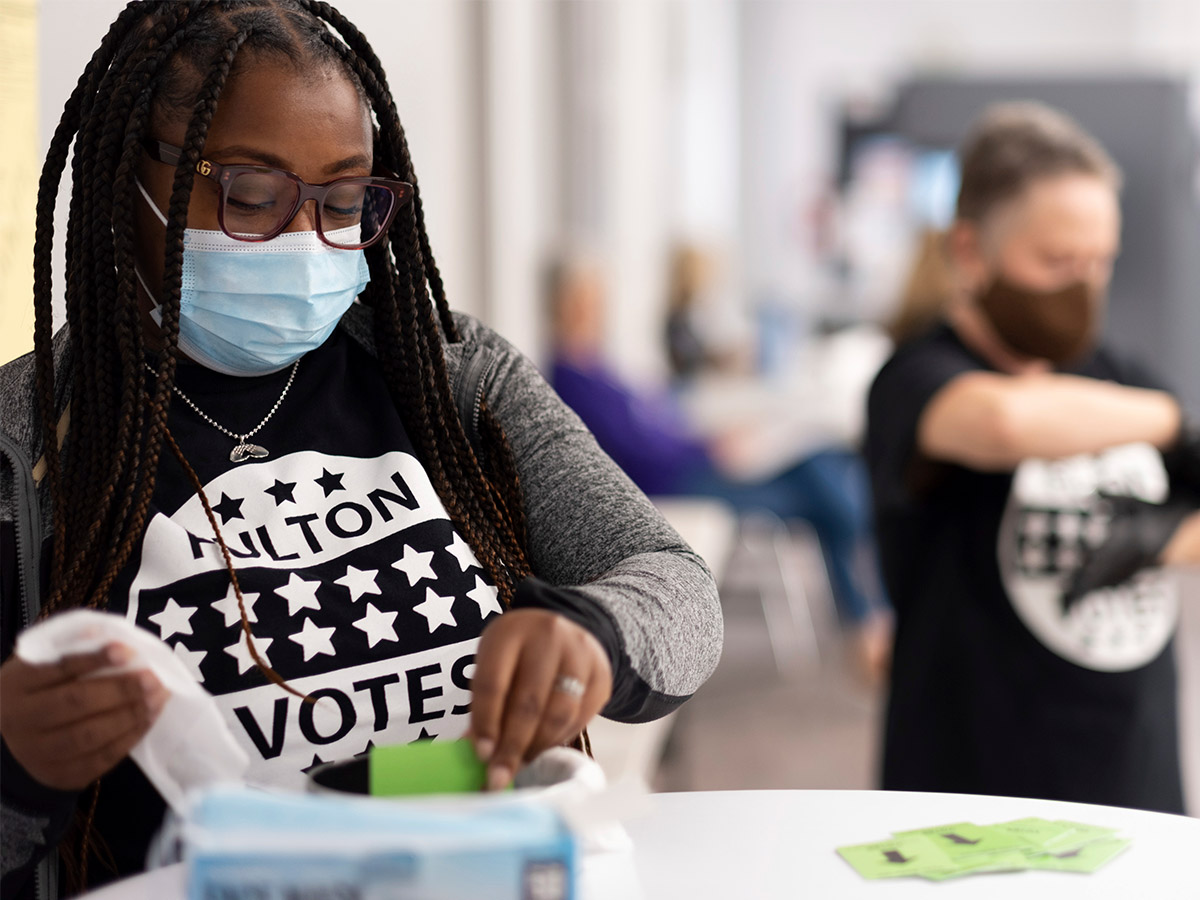

A poll worker in Sandy Springs, Georgia, a suburb of Atlanta.

AP Photo/Ben Gray

November surprise

Harvard analysts discuss Democrats’ ‘red wave’-defying performance, signs of desire for return to election normalcy

Several key congressional seats remain in play, but one thing most political reporters and pundits agree on is that the results from Tuesday’s midterm elections have been a surprise.

Many observers had been expecting inflation to be a singular issue, with voters blaming the Democratic president and Congress for their economic pain, resulting in a so-called red wave of GOP victories.

Instead, Harvard analysts say, backlash against Republicans over the Supreme Court’s overturning of abortion rights played a bigger role than anticipated in some states. Perhaps more important, they saw signs of strong support for the nation’s electoral system.

“Democracy is on the ballot every time we’re voting, but it seemed particularly important for this election in response to Jan. 6, in response to the Dobbs decision [that overturned Roe v. Wade], and in response to those who are running who are election deniers,” said Natalie Tennant, a resident fellow at the Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics and former secretary of state in West Virginia. “Voters chose to stand up for democracy.”

Tennant, who was the Mountain State’s top election official from 2009 to 2017, says there have been pitched battles over “Stop the Steal” rhetoric there. She noted the rise in threats of election violence inspired by conspiracy theories, citing reports of armed partisan poll-watchers patrolling ballot boxes during early voting in Arizona last month.

“There was a lot of preparation and vigilance by a lot of different organizations like advocacy groups, national groups, local groups that become aware of what’s happening on the ground,” she said. “So there was that awareness. And then when elections came, it seemed as though there were still those people out, you know, partisan poll watchers, but election officials and nonpartisan poll watchers and advocacy groups were there also. And so I think that’s why you didn’t see as many problems.”

Maya Sen, a professor of public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, agreed that abortion was a powerful issue. She also saw signs that the future of democracy was a top priority for voters.

“There had been a surge in support for Democratic candidates in the wake of the Dobbs ruling [in late June], but then in the last month or so that seemed to ebb a lot and you saw stronger support for Republicans in the weeks leading up to the election. So I think a lot of people were essentially assuming that it would be this Republican ‘red wave,’” she said.

“I think the dominant narrative in the last month has been, ‘This is going to be about the economy. This is going to be about rising prices; it’s going to be about inflation; it’s going to be about interest rates; and it’s going to be about a slowing housing market; and that none of those things are good for Democrats.’ The earliest data on this, that I’ve seen at least, suggested that was indeed a concern, but people were also concerned about democracy and the health of democracy.”

In addition, she said, “Given overriding narratives about the economy, a salient concern was also about abortion. There was pretty strong electoral blowback against constitutional amendments, or restrictions on reproductive rights access in Vermont, and California, Michigan and Kentucky.”

Sen said she was pleased to see a possible shift in attitude among some members of the far right. “We’ve had several Make America Great Again candidates who’ve been defeated who actually have conceded their election results, and I think that’s a really important step, suggesting a willingness to re-establish the norms of concession, which are actually really important norms.”

Raul Alvillar, who directed the Biden-Harris campaign in New Mexico and is now a fellow with the Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics, highlighted lessons for the Democrats.

“A lot of pundits were saying [the main issue is] the economy, which it is, and Democrats should talk about the economy and inflation. But it’s important for folks to talk about the issues that resonate with their voters and their constituents, and I think we saw that in this election,” Alvillar said.

“We saw it happen in a red state like Kansas, where they rejected a ballot initiative that would allow it to go to a vote and make abortion illegal,” he said. “And so I think that when you see that kind of civic engagement and that kind of engagement by the voters in a state like Kansas, that’s a good indicator of what you could see in the future.”

Alexander Keyssar, a Kennedy School historian and the author of “The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States,” said the midterms, like other recent elections, exposed key gaps in polling. He also welcomed the message that independent voters sent to election deniers.

“There’s a lot we don’t know right now,” he said. “But we do know several things. One thing that’s clear is that the polling, not for the first time, has been very unreliable and that we shouldn’t pay that much attention to it. Pollsters don’t know how to predict the turnout and especially in an off-year election, when at least half the electorate is not going to show up, what really matters is who shows up.

“The second thing that struck me so far is that there’s clearly a slice of the electorate, at least in most places, which is not particularly pro-Democratic Party, and is basically centrist or independent, or maybe even slightly Republican-leaning. But which does not want to support MAGA candidates and election deniers. We have to remember that the MAGA candidates and election deniers got a lot of votes, but that there was a slice of the electorate that won’t go there. That seems very important.

“There are many millions of people who did support election deniers and did support Trump candidates,” he said. “And that suggests ongoing tensions and conflicts are not going to go away.”

Keyssar said the midterms confirmed how much the nation appears to be in political flux. “The notion that the party in power loses a lot of seats in an off-year election is one of these political science-y kinds of predictions, which is true until it’s not. And the fact is that our political context right now, with the extent of polarization and with this relatively new expanded version of rabid election denial, is something new.”