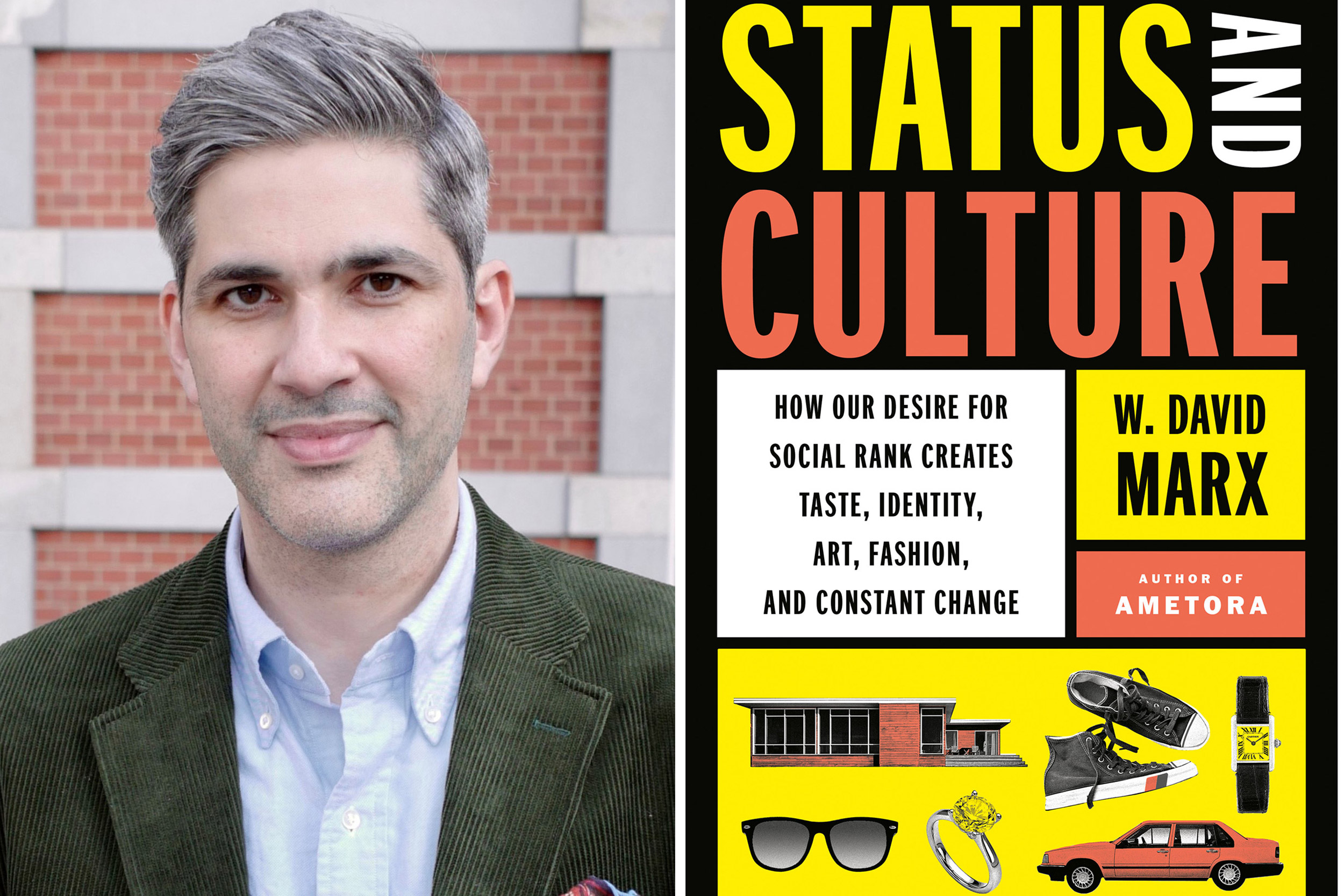

Author W. David Marx.

Courtesy of Penguin Random House

Keeping up with the Joneses 2.0

W. David Marx’s new book looks at our drive to seek, maintain status, how we signal our place in hierarchy to others, how social media is changing things

In a new book, “Status and Culture: How Our Desire for Social Rank Creates Taste, Identity, Art, Fashion, and Constant Change,” author W. David Marx ’01 looks at how our cultural tastes, demeanor, speech habits, and fashion choices transmit information to others about who we are and our social status. He argues that our need to seek or maintain status underlies all our choices, from which TV shows we watch to which wines we prefer — as well as what we choose to avoid or disdain.

Marx spoke to the Gazette about the ways the internet and social media are changing the social importance of art and culture, and how traditional markers of status — family connections, education, and career, among them — have started to decline in value while money and fame are on the rise. Interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

W. David Marx

GAZETTE: When people hear the word status, they usually think of someone’s perceived importance or social rank based on wealth and/or celebrity. But you’re talking about something much broader and more universal. Can you explain what you mean by status and why we feel compelled to seek it?

MARX: I’m using the sociological meaning of “status,” which is describing an individual’s place in a hierarchy. Each location in the hierarchy provides a certain amount of benefits. If you move up and have high status, you get more benefits. If you move down, those benefits are taken away from you.

All individuals have a status. Groups also battle it out in society for status, since the association with those groups provides their members more status. If you think about status in that sense, you start better understanding the relationships between individuals and society: how individuals arrange in these hierarchies, how group conflict emerges, why there are certain behaviors at certain levels of these groups, and the interactions that cause these different parts of culture — taste, fashion cycles, subcultures, how historical memory is created, why authenticity is important, etc. So, in this one book, I’m trying to look at the principles of status and how they create the universal rules of how culture gets formed and why it changes.

GAZETTE: Historically, people around the world attained status through family, ethnic or religious affiliations, age, sex, wealth, or occupation. What’s changed?

MARX: Ever since the development of liberal democratic society in the 18th century, someone can come from nothing, make money, and move up the status ladder. Today, we believe people should receive status by the content of their character, their achievements, and their contributions. In theory, you should receive status from making contributions or incredible achievements, which also bring fame. With the rise of social media, fame becomes a goal in itself and its own source of status. TikTok stars are being invited to the Met Gala. They’re standing beside all these legendary personas from other fields and entertainers. Of course, status is always ambiguous. There’s no formal status ranking. It’s always in negotiation and changing, and it’s all contingent. Our beliefs change over time about who we think should be on top. So today, we have all these social media stars rising and young people think, “These are the people I watch every day; of course, they should have status,” but previous generations think they should not. Overall, status criteria like cultural capital, educational capital, and occupational capital are on the decline, and money and fame are ascendant.

“In this one book, I’m trying to look at the principles of status and how they create the universal rules of how culture gets formed and why it changes.”

GAZETTE: You say we are always looking for clues about someone’s status. Where are we looking and what are we looking for?

MARX: Every time we meet a stranger, we have to understand their status level to understand how to treat them. Maybe for some people it’s more conscious, but it’s generally an unconscious process. We can’t help but use all our senses to understand: Who is this person? There are signals, which are intentional things that people do to show their status position or to classify themselves as “I’m this” or “I’m that.” Then there are cues, which are involuntary things people can’t control. I’m from the South, so I used to say, “Y’all.” When I went to Harvard, within about a week, I was saying, “you guys.” But I can’t stop saying the number “10” as “tin.” It’s those kinds of verbal tics that associate us with certain groups, and those groups are associated with certain statuses. Since we know these patterns, we acquire status symbols to signal our successes and our affiliations with high status groups. Status only exists if we get it from people, and we only get it from people if they can interpret us as somebody with high status. And so, we have to do a lot of symbolic play in order to get the treatment we want.

GAZETTE: Though everyone does it, few of us admit that we’re seeking higher status when we do or buy things. You say we need an “alibi” to justify our actions. What do you mean?

MARX: Alibis, which is an idea from Jean Baudrillard, are really important because, first and foremost, people with high status don’t need to signal high status. Every time you look like you’re trying to get status, you are revealing that you don’t have status. So, it’s important strategically that you do not show that you are trying to get status. You need an alibi for your status-seeking actions. Growing up, my family always drove Volvos. My parents always said, “We only buy Volvo cars because they are the safest cars.” But Volvo was marketing to people like my parents who hated the intense hierarchy of American car companies where Cadillac was on top, and Dodge was at the bottom. The Volvo was the perfect car for this kind of upper-middle-class, professional, academic household. “We don’t care about cars” — that was the market. But their alibi was, “It’s the safest car.”

The best status symbols come with three things: what I call cachet, which is a symbolic association with high status group. The second is signaling costs. There has to be something that demonstrates that you have high status in order to pay those costs. Obviously, an expensive car has a high signaling cost because you’d have to have a lot of money to acquire it. But the cost could also be taste or information. And then, third, it has an alibi — you bought it for some reason other than status-seeking. We feel shame around status-seeking, so we are in search of a better way to explain our behavior other than “Oh, it was trendy” or “I’m doing this to show that I can afford it.”

GAZETTE: The internet has radically changed how we signal status to each other and drained some of the value from cultural signifiers. What’s different?

MARX: When we think about culture, we often think about it from the perspective of pure enjoyment. A movie or music comes out, we simply enjoy it, or we don’t. The status that you get from appreciating something, however, does add value to the experience, whether we like it or not. There’s been a lot of research recently in neuroscience where they let people drink wine, and then they look at their brains. They think it tastes good. Then they tell them it’s an expensive wine and not only do they say it tastes better, but their brains seem to appear that they’re enjoying it more. So, status imbues our cultural experiences with more pleasure, which makes it more complicated to make judgments on culture.

We live in a world of plenty. There are more songs than we can ever listen to, more films than we can ever watch. We may enjoy the promises of such abundance, but if we go to someone and say, “I just saw this great film last weekend,” and they don’t know what it is, then a lot of the social value has been taken away from that film. The internet speeds up this devaluing in a few ways. Two of the really important signaling costs for culture, especially among the professional class, are information and access to product. We now live in a world where the internet makes everything knowable. If somebody knows something, we don’t find that interesting anymore because we assume that everything is knowable. If it was difficult to get, we don’t care because we also believe everything is acquirable.

The New York Times did an article about these high-top sneakers the Taliban wear made by a Pakistani brand called Cheetah. And some fashion people in the U.S. were like, “I gotta get a pair of these Taliban high tops,” maybe as an ironic joke. If this were 20 years ago, how in the world would you get your hands on a pair of sneakers from Pakistan? But within weeks of that article, e-commerce sites in Pakistan popped up to ship them worldwide for not very much money. Where these acquisition costs go down, that drains culture of status value.

With the internet, that’s the paradox: We have more things, but they seem to be more devalued.

“Then there are cues, which are involuntary things people can’t control. I’m from the South, so I used to say, ‘Y’all.’ When I went to Harvard, within about a week, I was saying, ‘you guys.’”

GAZETTE: There’s so much creative material being produced and shared by so many people, it’s much harder for new artists to break through. Even when successful musicians, like Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar, release innovative records, their hold on our attention span only lasts a few weeks. What’s going on?

MARX: Obviously, there’s a lot of innovation still happening around the world. My question is: Why isn’t the cycle of innovation of things from the outside coming in and really changing the mainstream, and why does so much of mass culture seem to be simplifying? Most certainly, a key factor is algorithms on internet platforms. In the past, if you went to a record store, the record store clerk knew more than you. And so, if you said, “I like The Smiths,” they would say, “Well, have you listened to all these albums on Rough Trade?” Half of that was him showing off that they knew more than you, but it was always pushing you to go deeper. The algorithm is the exact opposite: “If you like this, here’s a video everyone likes that is somewhat tangential to what you liked” and is most likely to be less sophisticated.

With young creators, I don’t get the sense that generation worries about “Am I as good as the artists before me?” There’s a real sense of democratic participation. People don’t seem to be carrying the burden of, “Wow, there’s so much innovation in the past. How am I going to beat that innovation by doing something new?” That process seems to be done, for the moment, and young people are just living in the now, trying to quickly get things out. They’re in a constant cycle of production. And that certainly is a way to keep yourself entertained. That is a model for culture, but it can be somewhat exhausting for older generations. And that functions as a way to keep us out of it. One of the things about TikTok is that if you’re in your 40s and you don’t understand it, that’s the point. It’s not supposed to be for you. The same way when I watched MTV in the ’90s, and my mom walked in and said, “Turn that off,” because she thought it was all garbage, I was proud of that. I thought, “Well, you don’t get it.” Every generation needs some sort of barrier to the generation before, and I think this focus on speed functions as a generational barrier for young people.