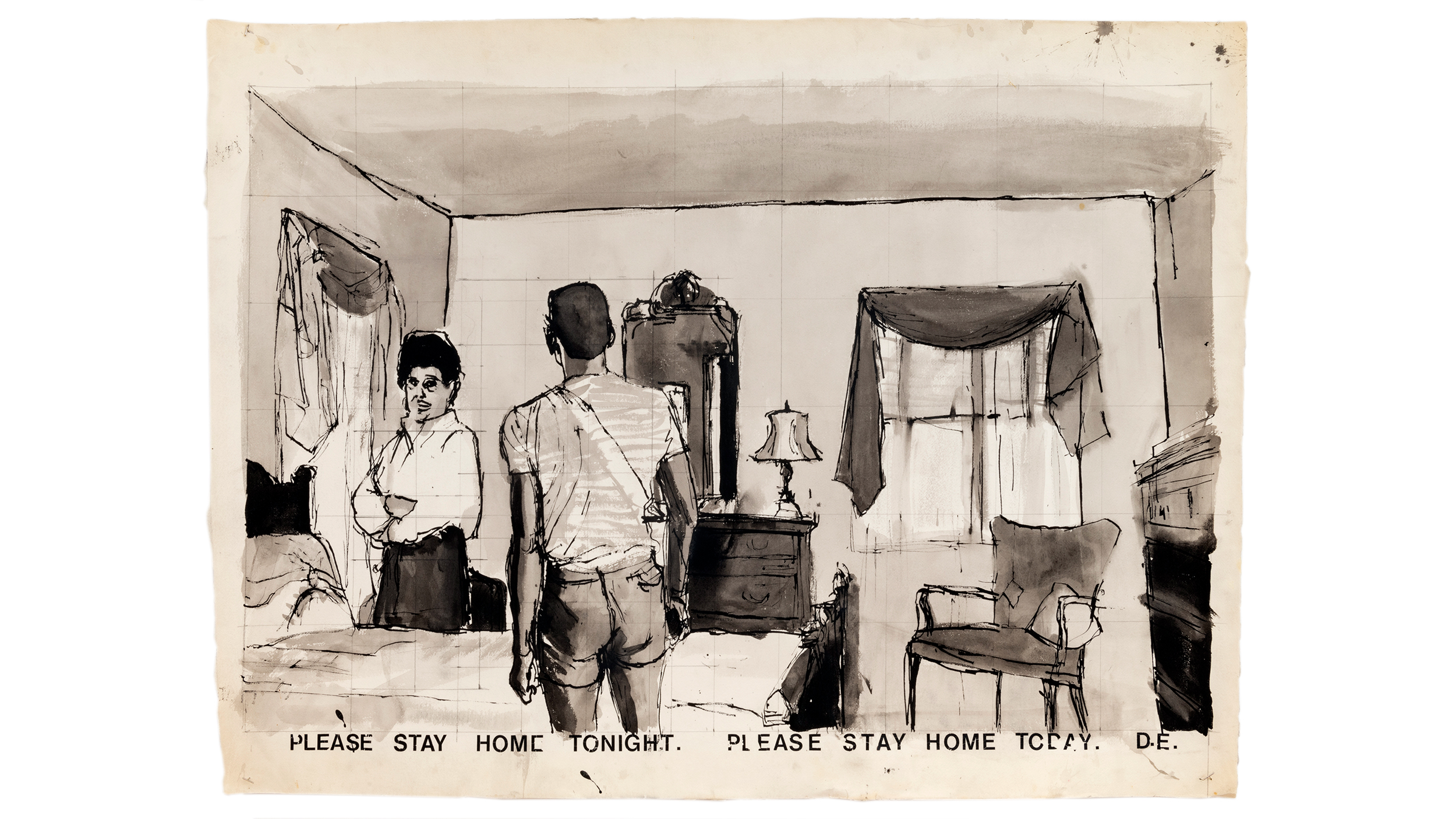

Darrel Ellis, Untitled (“Please Stay Home Tonight, Please Stay Home Today”), ca. 1981-1985. Graphite, pen, ink, and ink wash on paper.

Image courtesy of Candice Madey, New York; photo by Adam Reich

Plea from 1980s New York: ‘Please Stay Home’

With themes of family history, identity, loss, Darrel Ellis exhibition at Carpenter Center looks back yet feels of the moment

Before Darrel Ellis died, at age 33 of AIDS-related causes in 1992, the Bronx-born, mixed-media artist was exploring themes uncannily relevant in the COVID era, from the fragility of life and relationships to Black identity and civil rights. So it’s fitting that a new exhibition of his work — opening Thursday at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts — takes its title from his pen-and-ink drawing “Please Stay Home.”

As a plea during a pandemic or a request from a lover, the phrase is ambiguous yet fraught with meaning, curator Makeda Best said. “We don’t know the context of the subject of the drawing” from the early 1980s, which depicts two people standing in a bedroom, “or why he wrote that on the work.” However, it “brings out important trends that were really accentuated by the pandemic.”

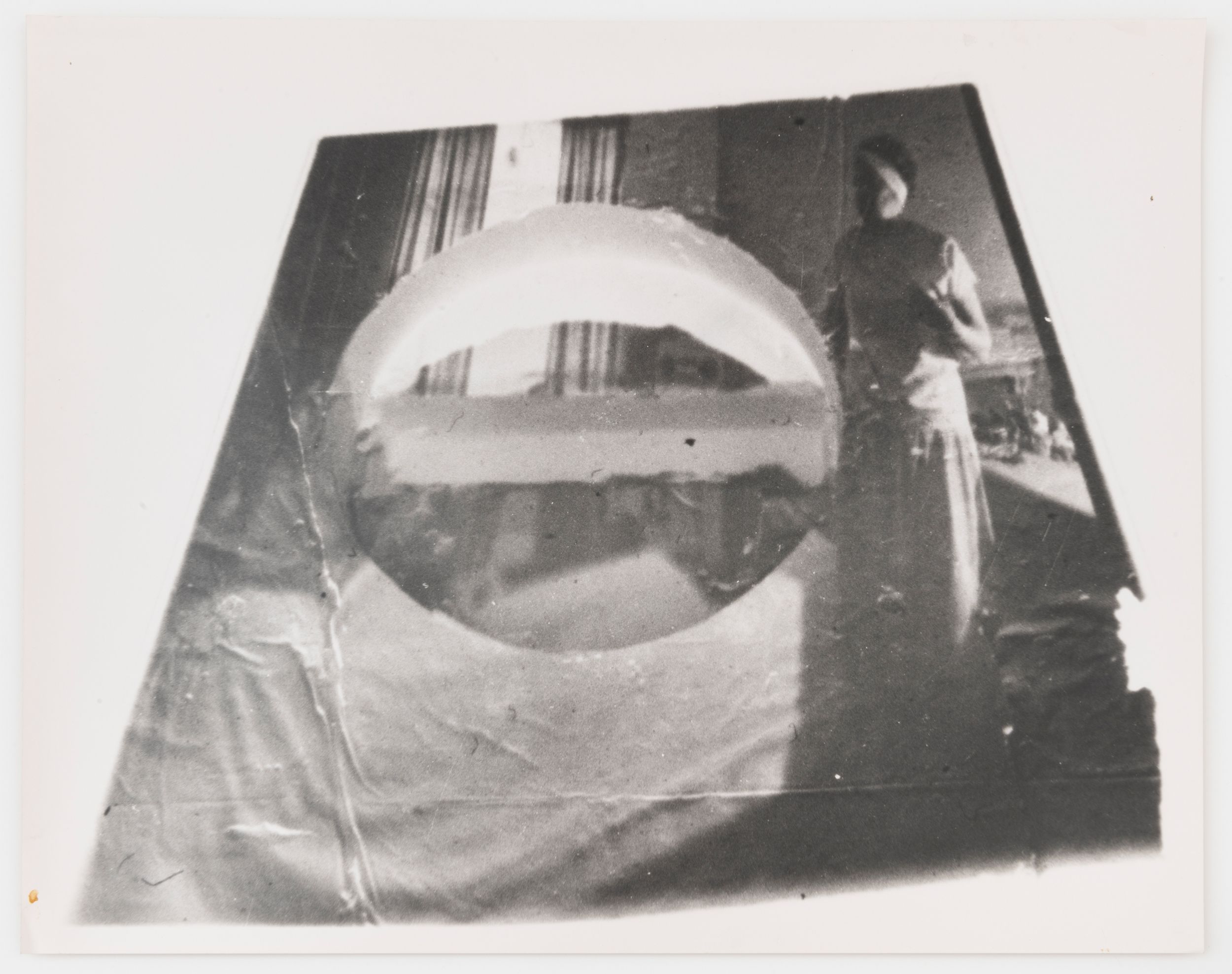

Family history is key. Much of Ellis’s prints, paintings, and photos are reinterpretations of images created by his father — a professional photographer who was killed by police two months before Ellis was born.

Darrel Ellis, Untitled (“Grandparents Dancing” and “Mother’s Bedroom”), ca. 1981-85, 1987–91. Gouache and ink on paper and gelatin silver print.

Images courtesy of Candice Madey, New York; photos by Adam Reich

“New York in the 1970s and ’80s was a very different world of Black life,” said Best, the Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography at the Harvard Art Museums. “The show is really about this kind of interiority, about Black identity, and that really points to this long story of Black civil rights and Black identity, but also the intergenerational qualities of it.”

Citing Ellis’s use of painted-over or manipulated photographs, Best said the artist explored “the intergenerational dialogue with past Black identities and contemporary Black identities.”

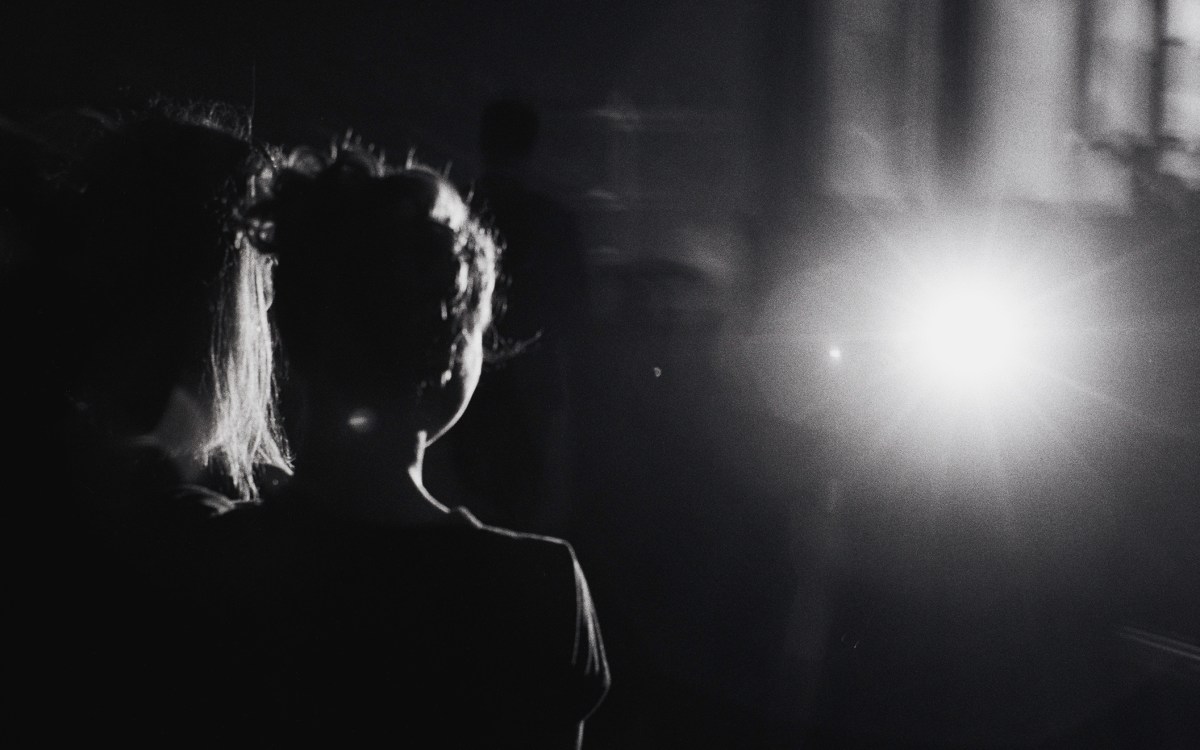

Curator Makeda Best.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Contemporary artists Leslie Hewitt and Wardell Milan created pieces responding to Ellis’s work for the show. Milan said Ellis was “making work during that time when not only the gay community but also the Black community were even more marginalized than they are now.” He was “part of both of those communities in New York City when the AIDS crisis was just beginning, and these communities were dealing with devastation of that.”

“The show is really about this kind of interiority, about Black identity … but also the intergenerational qualities of it.”

Wardell Milan, “The Edge of Town: Hollywood Hills,” 2021. Charcoal, graphite, oil pastel, colored pencil, pastel, yupo paper, cut and pasted paper on inkjet print.

Image courtesy of the artist and David Nolan Gallery

Since the murder of George Floyd and the global Black Lives Matters protests, Ellis’s work has new resonance, said Best. “Through small exhibitions and a major touring retrospective, Ellis’s work is finally gaining widespread attention. I feel like the work is just more meaningful now.”

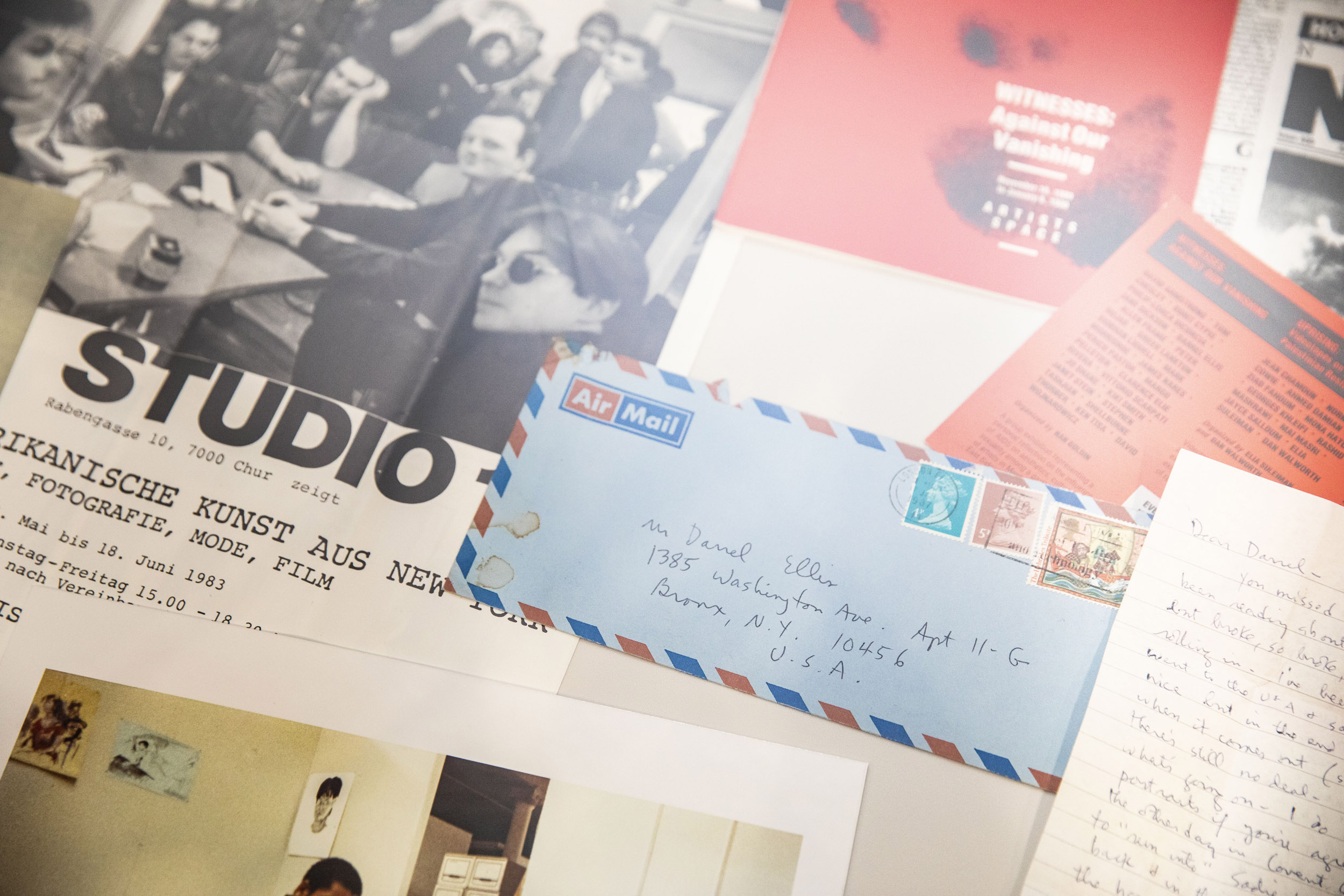

To provide a personal, political, and historical context, the show includes ephemera as well as photos by the artist’s father, Thomas Ellis, and photographs of Ellis by his friend Allen Frame. This allows viewers insight into “the ways in which Ellis is thinking about his identity as a Black gay man, and the way his family and their community lived and the lifestyle that he sees in the pictures his father made versus the world that he was growing up in,” said Best.

The exhibition includes personal papers and photographs of Ellis.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Ellis was “very much interested in the history of photography and also interested in the histories of other art,” said Best. “As a curator, I love hearing how he enjoyed visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art, looking at Bonnard.”

Considering Ellis’s body of work, she mused, “There are interesting stories here of familial communities, artistic communities, and how those have changed over time. Where are those communities now? How are communities different?”