This mixed media piece by Rachael Jonas-Closs includes rusty metal, seashell, and other materials.

Image courtesy of Rachael Jonas-Closs

When you’re a watercolorist and your day job is at Harvard

Staffers exhibit their art across range of media in annual University show

We are more than our jobs. That’s the prime takeaway from the 2023 Harvard Staff Art Show, which held its virtual opening on Feb. 9. With more than 370 works from 222 artists, the exhibit showcases the creative endeavors of employees in almost every Harvard School and unit. This year, the annual event’s third iteration as a University-wide show, the display is once again hybrid, with a Virtual Gallery as well as three artist events and six in-person exhibits across campus, staggered throughout the spring.

The non-juried show sent out a call for submissions last fall, inviting all members of the staff to share their “whole selves.” “We try to be as inclusive as possible,” said Roba Khorshid, a member of the show’s volunteer steering committee and a participating artist. Encompassing visual arts from film to fashion, portraiture to printmaking, with every conceivable medium in between, the range as well as the quality of the works on display is impressive.

Having grown every year, the show is now also global, with entries like “Flying Together,” a video by Larissa Leal, a program assistant in the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies in Brazil. “The whole goal of this show is to connect people to create a community,” said Khorshid, the senior program and events coordinator for the Office of the Senior Vice Provost for Faculty Development and Diversity.

Fiber artist Tracy Blanchard is one of the organizers of an in-person exhibit going up at the Harvard Law School’s Langdell Library March 13–23. In addition to organizing the 25 artists she has gathered thus far, Blanchard, who works as a program coordinator in the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program, will be displaying two pieces of her own that can be viewed online. Using beads and shells as well as thread and cloth, these pieces find political and spiritual inspiration in what has traditionally been viewed as a “female” craft.

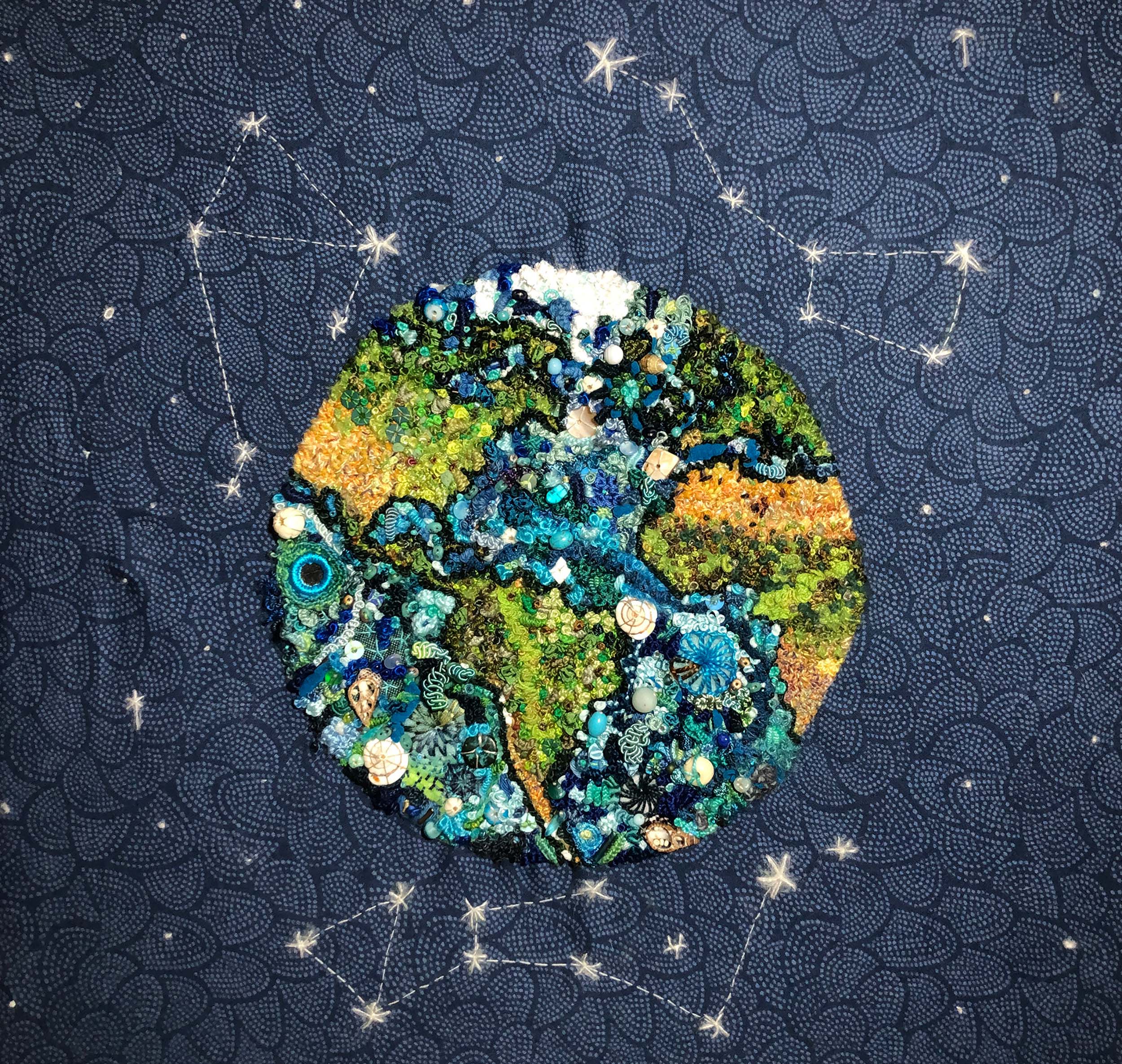

Blanchard comes from a background in monoprints and bookmaking, which incorporates stitching together pages. She initially had found herself dismissing the sewing and knitting skills she’d been taught as a girl. However, her bookmaking required the skills, “and with COVID, it all sort of exploded,” she said. Isolated, she began taking online stitching classes to socialize. Before long, she was exploring her spirituality in pieces like “She’s Got the Whole World in Her Hands,” which uses embroidery to create a detailed and textured view of the globe. She soon also found herself re-evaluating the gendered nature of fiber arts.

“There is something that is comforting and empowering about it,” she said. Fiber arts — which are often dismissed as a craft — “is still very much a woman’s space,” she said. “We could just do all these things and not have to constantly be worrying about being judged. It’s a lovely little paradox, which I think is great to play in.”

“She’s Got the Whole World In Her Hands” by Tracy Blanchard (cotton, thread, beads, shells).

© Tracy Blanchard 2022

Rajesh Mohan’s beautifully photographed nature films could seem a far cry from his Harvard job as the associate director, ATS – Reporting Analytics and Integrated Data, HUIT. His “Drama in the High Arctic,” for example, took him to the ocean cliffs of Svalbard, Norway.

Discussing this documentary about the thick-billed murre, an at-times-heartrending account of the obstacles the aquatic birds’ chicks face on their way to maturity, he recalled an intense emotional connection. “Amidst the din of 60,000 birds,” he said, he found his story. “The lost chick in the video actually came to us crying. It was heart-wrenching. I could feel the story running in my head as I filmed different sequences, and everything fell into place. I think I was extremely lucky.”

Turning to his more experimental work in ultra-low speed, Mohan acknowledges some overlap with his day job. Filming with a Chronos 2.1 camera that can shoot 1,000 frames per second (as opposed to normal film’s 24) allowed Mohan to slow each second to 40 seconds. “My day job requires me to design and implement complex data systems, and perhaps it trained me to use the technology side of this specialized filming and processing with relative ease,” he noted.

This process reveals interactions in the wild that would otherwise be inaccessible to the human eye, such as a butterfly knocking a bee off a blossom or the play of water as a heron lunges for a fish. The result is beautiful, and also calming. An oncologist friend, Mohan related, streams his slow-motion videos in his waiting room. “We are constantly talking about stress and needing to unwind,” said Mohan. “I hope these videos, in a small way, help with that.”

For Rachael Jonas-Closs, the work sometimes bleeds through. “My work features a fair amount of scientific thinking,” said the aquatic animal technologist in the Systems Biology Department. Her striking assemblages pulling together found materials from leaves to crumbling brick “use a fair amount of trial and error,” she explained.

At times, the connection is more pronounced. “I spend a lot of time thinking about water and have developed a lot of specialized and minor skills for controlling its flow.” For pieces like “Flooded Poplar I,” she applied this knowledge — as well as an element of chaos — for a subtly graded, fan-like image. “Liquids do what they want and in my poplar pieces I can’t control them,” she said. “But I can use gravity and adhesion to get them to cooperate with me.”

Although Jonas-Closs’s choice of medium originated in strict budgeting, her decision to use found objects — purchasing only Elmer’s glue, vinegar, and wood — is now a conscious creative choice. “I know that my aesthetic preferences are not shared by everyone, but I genuinely find these chunks of detritus — both natural and man-made — attractive in their own way,” she said. It is also rooted in her childhood: “I have long attributed my love of rust to growing up next to the Mattapan trolley,” she said. “While other kids went digging for buried treasure and found nothing, I found rusty railroad clips.”

To build up her assemblage library, Jonas-Closs collects items that attract her eye and that she trusts she can incorporate into a larger piece. Not every found object makes for good art, she said. “There are beautiful colors in rotting wood, but experience has taught me that I can’t preserve it well,” she said.

This is Jonas-Closs’ first time showing her work. “A lot of people see assemblage as just trash,” she explained. However, she added, “This work is good for me and even though I am never 100 percent satisfied with it, I do genuinely like the products I’m making these days. The staff art show was a great opportunity to start sharing this part of my life.”