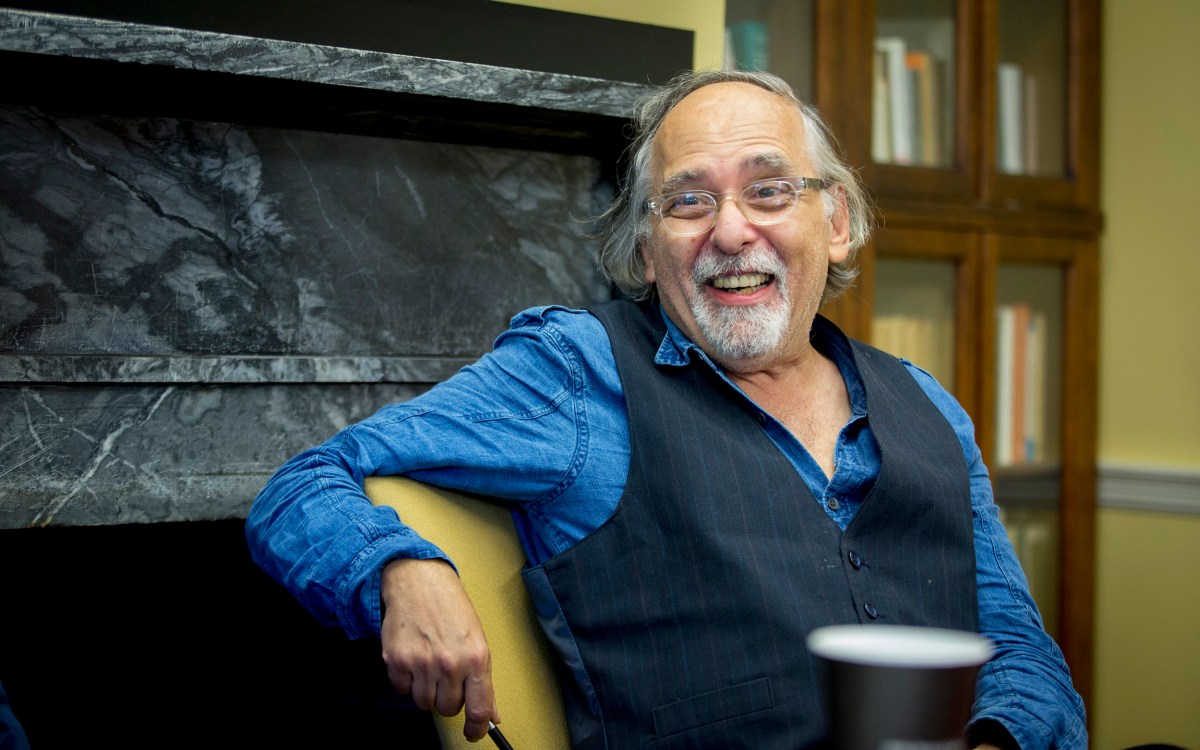

Photo by Scott Eisen

Tony Kushner on Jewishness, Spielberg, ‘unsafe’ art

In Harvard visit, Pulitzer-winning playwright reflects on roots, writing (and rewriting), empathy in a darkened theater

In a sprawling discussion of Jewishness, Stephen Spielberg, and the arts, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, screenwriter, and activist Tony Kushner entertained the audience at Sander Theatre from his very first response to an interviewer’s question.

Stephen Greenblatt, John Cogan University Professor of the Humanities and a fellow Pulitzer honoree, opened Tuesday’s event, which was sponsored by the Center for Jewish Studies, by asking about Kushner’s relation to his Jewish identity.

“It depends which day of the week you ask,” the playwright responded, to laughter.

The 66-year-old then described growing up in a Reform Jewish family as a member of a very small Jewish community in Lake Charles, Louisiana, “none of whom for some reason had Southern accents.”

“Over the years, my identification as a Jew has deepened,” he said. “It’s an incredibly important part of who I am. I feel deeply indebted to Jewish ethical teaching, to Jewish notions of fairness and decency and responsibility. I love Jewish dialectics: the ethical mandate to not be a fundamentalist — to be a reader of text and an interpreter of texts.”

Recalling that “warm, vibrant” minority community of approximately 100, in a Louisiana city of approximately 60,000, he noted that the experience helped him come out at age 26.

“I felt I had a template for how to be a gay man derived entirely from the relationship I had to my Jewish identity,” he said. Although he experienced some anti-Semitism, he recalled, he had learned “it was their problem, not our problem, and we should be proud.”

His experience of anti-Semitism, he said, contributed to his screenplay for “The Fabelmans,” which is based on Spielberg’s childhood. “We’d both had a low-level experience of bullying from anti-Semitic bullies,” recalled Kushner. “He had one bully, I had two, so I asked to bring my two bullies in.”

“The Fabelmans,” Kushner’s fourth and most recent collaboration with the filmmaker, was a project that the two had discussed for years and which finally got underway following the death of Spielberg’s father in 2020 (his mother had died in 2017).

“That and lockdown made Stephen decide he wanted to work on this idea,” said Kushner. “I interviewed him for about two months, then I went away and renamed the characters and wrote it as a narrative. I’ve never written anything that fast.”

That reminiscence led Greenblatt to ask when, if ever, the playwright considers a project done. In the case of a film, Kushner explained, it’s simple: At some point the filmmaker “locks” the project and it is closed — nearly always. “I actually got him to reopen ‘Lincoln’ about four lines that he’d cut,” said Kushner about Spielberg. “I was right, too.”

His plays, by comparison, are never finished, he said. In fact, whenever his two-part Pulitzer- and Tony-winning “Angels in America” is restaged, “I get involved in rewrites,” he confessed. “Who’s going to stop me?” (“Angels in America, Part 1” will be presented at the Central Square Theater April 20-May 21.)

“It’s so rare that you encounter a work of art that it makes you feel unsafe. In the rare moments that you do, you should treasure it.”

The topic of theater and its relative openness led to discussion of problematic plays, like Shakespeare’s “Merchant of Venice.”

“Should it be banned?” asked Greenblatt.

“God, no,” responded Kushner. Acknowledging that Shakespeare “accepted many received ideas about Jewishness,” and noting that “it was written at a time when there were no Jews in England,” Kushner went on to describe the humanity that the playwright grants the Jewish character of Shylock, despite the use of stereotypes: “’Hath not a Jew eyes?’” he quoted. “That transcends prejudice.”

Art, he continued, should not be condemned for being “unsafe.” “It’s so rare that you encounter a work of art that it makes you feel unsafe,” he said. “In the rare moments that you do, you should treasure it.”

Recalling monumental performances by Fiona Shaw as Euripides’ murderous “Medea” and Brian Cox in the title role of Shakespeare’s disturbing “Titus Andronicus,” he described relishing the experience. “You watched a human being pushed to a point,” he said of Cox. Afterward, “the houselights came up and everyone just sat there. Nobody moved. It was the opposite of safe.”

This electrifying — and sometimes discomfiting — experience is “the deal that you make when you go into the theater, the deal that you make when you go to bed and you dream,” he said. “Medea is not really going to come off the stage and kill you.”

However, with art, particularly with live theater, “you get to see things that are unbearable and unimaginable and can’t be countenanced when you’re out in the world walking around. But in the dark …” He paused. “It’s one of the reasons that we have art.”

Rather than “protecting yourself from extremes of feeling,” he said, “it’s important to have those encounters.”

As the conversation progressed to take writing in languages other than English — the Yiddish in “Angels” or the Spanish Kushner used in his update of “West Side Story,” another Spielberg collaboration — the playwright dismissed the idea that viewers might get lost. “A great pleasure of art is the way it exercises our empathic power,” he said. “We listen on many, many levels and we remember on many, many levels, and if the playwright has done his job, you won’t be worried about it.

“Art gives us a chance to experience the stories and lives of people who are not like us.”

Kushner’s appearance constituted the Doft Lecture, the largest annual event presented by the Alan and Elisabeth Doft Lecture and Publication Fund.