Spencer Jourdain gazes at the tribute to his father, Edwin Bush Jourdain Jr., after its recent reveal in Winthrop House.

Photo by Kevin Grady

How student led protests to open College dorms to Black freshmen

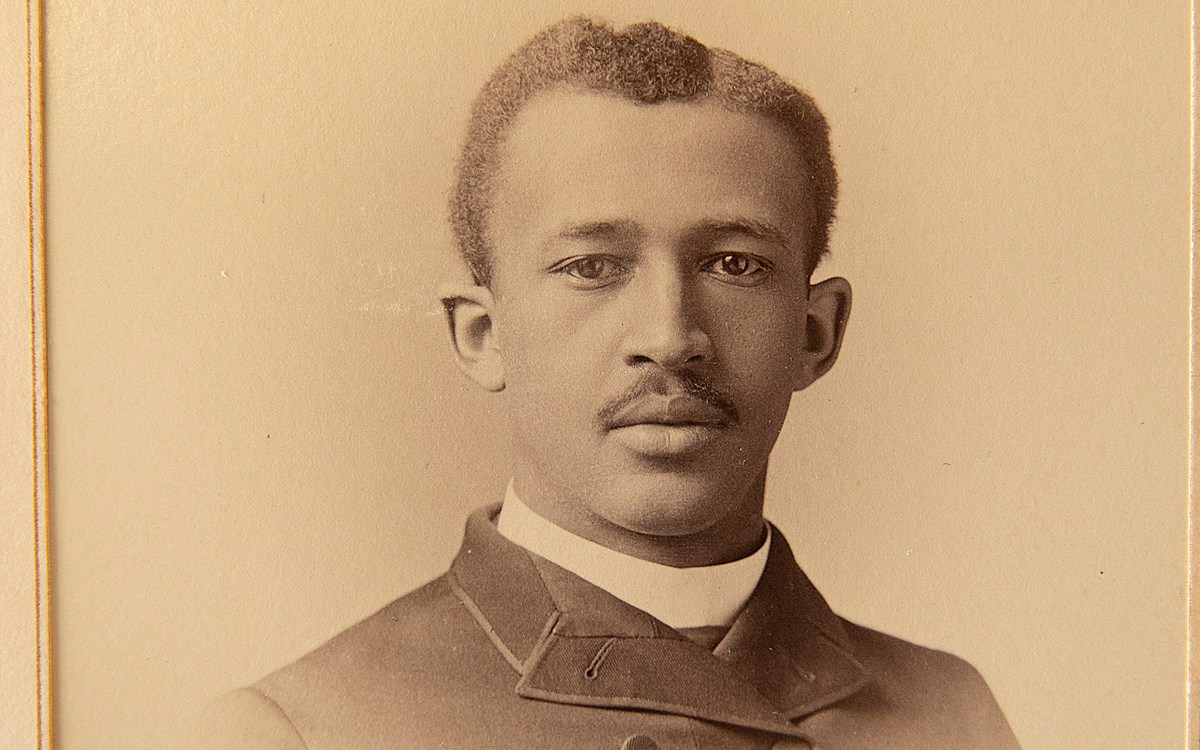

Portrait honoring Edwin Bush Jourdain Jr., who confronted President Lowell over policy in ’20s, unveiled in Winthrop House

When students enter the Senior Common Room at Winthrop House, they now see an image of Edwin Bush Jourdain Jr., Class of 1921, the man who launched protests that ended discrimination against Black students in Harvard’s freshman dormitories 100 years ago this spring.

The portrait, beside ones of legendary civil rights figures W.E.B. Dubois and John Hope Franklin, was unveiled on March 31 in a celebration attended by family, staff, and students.

Vice Provost for Special Projects Sara Bleich spoke to the gathering. The Report of the Presidential Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery, released last April, “unveiled a number of very difficult truths; truths that we are reckoning with as a society,” she said. But “the report also identifies some of the really courageous individuals, some of the first Black students at Harvard who pushed back, who drove toward equity. And Edwin Jourdain is one of those people.”

The portrait captures Jourdain as a student, not yet 20 years old. The image was chosen by Edwin’s son Spencer Jourdain ’61 in hopes that today’s Harvard students will recognize themselves in the image of a predecessor whose belief in a better University drove him to meet with Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell to press for a change in policy.

“Dad loved Harvard more than any other person I ever met in my life,” said Jourdain. “He had a way of being calm, and that’s what I see when he was confronting President Lowell. He knew who he was, and he had a long history of abolition in his family.”

Jourdain’s father was a New Bedford attorney — one of the first African Americans to graduate from the Boston University School of Law — and was, with Du Bois (Class of 1890; A.M. 1892; Ph.D. 1895), a founding member of the Niagara Movement, the precursor to the nation’s oldest civil rights organization, the NAACP.

“When I think about my grandfather, at the age of 21 … seeking an audience with President Lowell to protest that policy, I see an act of moral courage.”

Jacqueline Jourdain Hayes

So, in 1921, when Harvard revoked incoming Black freshman William J. Knox Jr.’s dormitory assignment, Jourdain, who had lived in the hall during his freshman year, accompanied his childhood friend to a meeting with Dean Philip Chase to ask why Knox was now barred.

They were told that Lowell’s policy was to exclude Black students from the freshman dormitories on the basis that the University could not force white students — particularly those from the South and West — to live alongside Black ones.

To Jourdain, by then enrolled at Harvard Business School, this was unacceptable. He met with Lowell, who told him, “It was the assumption from the start that no Negroes should occupy the freshman dormitories, and I was unaware that any precedent had been established to the contrary,” Jourdain recalled. Moreover, if it came down to a choice between integrating the dorms or ceasing to admit Black students at all, Lowell intimated he would not hesitate to exclude Black students from the University.

So Jourdain rallied members of the Nile Club, a social organization for African Americans at Harvard, to campaign against Lowell’s policy. Members of the club included many future scholars and leaders, among them the prominent civil rights attorney Charles Hamilton Houston.

By the summer, Jourdain and other students’ activism around the “dormitory crisis” had attracted national attention, including coverage in The New York Times. Some white alumni supported the movement; 149 signed a petition that likened the exclusion to Jim Crow policies.

In early 1923 Harvard’s Overseers approved a new policy establishing that “men of the white and colored races shall not be compelled to live and eat together; nor shall any man be excluded by reason of his color.” It was a ruling that walked a fine line, guaranteeing that all could live in the dorms but that individual white students would not be forced to live with Black students.

“When I think about my grandfather, at the age of 21 … seeking an audience with President Lowell to protest that policy, I see an act of moral courage,” said Jacqueline Jourdain Hayes ’89, J.D. ’92.

“He argued that while Harvard’s admission of Black students at that time was itself a renunciation of fear of difference, that Harvard could not truly achieve its aspirations — could not be truly courageous — until those students were offered the same housing opportunities as their white peers,” said Hayes.

Jourdain’s portrait at Winthrop House was unveiled as students continue to process the report’s findings and engage in difficult but necessary conversations about Harvard’s ties to slavery.

“I think this is encouraging, to see our faculty deans make an effort to bring portraits of people who look more like what Harvard looks like now, or what it should look like, a more diverse set of individuals who have just as important legacies, or even more beneficial legacies than some other people,” said Melanie Armella ’24. “There’s something catching in the air, I think.”

Later this spring, as part of a digital project that highlights the challenges and achievements of other early Black alumni, led by Alexandria Russell, a digital humanities research fellow for Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery, the Harvard Radcliffe Institute will launch an online exhibition featuring some of the Jourdains’ personal archival materials. Among them will be a transcript of Edwin Jourdain Jr.’s account of his meeting with Lowell.