A Harvard class tours Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Saying their names, remembering their lives

A visit to Royall plantation brings home ‘intimacy of slavery’ for students. Educational tours are part of Harvard’s deepening partnership with the museum.

A handful of Harvard undergraduates gathered recently before a plain white sign.

“This is one of the most important panels in the museum,” Kyera Singleton, executive director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, told the group.

Two students leaned in closer, squinting over rows of type. Nan. Ruth. House Peter. Forten Howard. Cuff …

“These are the Black women, men, and children who we know were enslaved by the Royalls over a 40-year period,” Singleton explained. “You can Google any member of the Royall family and find all you need to know about them. However, we cannot do the same thing with the enslaved people on this plantation.”

At least 60 people were enslaved at this site a few miles north of Harvard’s Cambridge campus, making the property’s 18th-century owners the largest slaveholding family in all of Massachusetts. Singleton, hired in 2020, makes it her mission to remember the lives represented by that sign. “We’re doing this work to make sure we know their names, and we say their names as much as if not more than the Royalls’,” she said in an interview.

Harvard Law School pledged $500,000 this year in support of the Royall House and Slave Quarters’ mission. Also announced was a University-wide commitment to working closer with the museum on research and learning experiences. Community partnerships are central to Harvard’s educational mission, said Social Science Dean Lawrence D. Bobo, who is also the W.E.B. Du Bois Professor of the Social Sciences. “But this one has the additional layer of speaking to issues attached to the Harvard Legacy of Slavery project.”

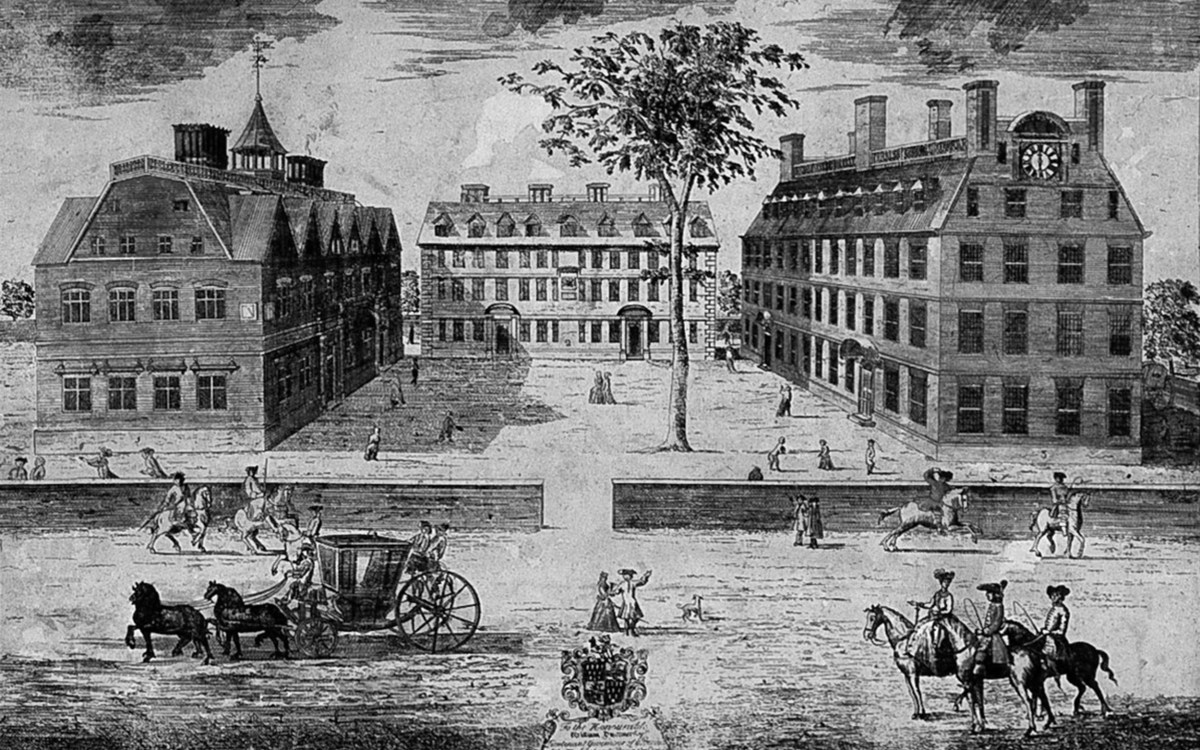

The first phase of that project, outlined in a report released last year, meant uncovering Harvard’s ties to slavery and the long history of racial oppression on campus that followed. Isaac Royall Jr., who died in 1781, bequeathed land to Harvard College, and its proceeds were used to establish the school’s first professorship in law. In 1936, the Royall family crest was even incorporated into the Law School’s official shield, which was used continuously until 2016.

Now in its second phase, the Legacy of Slavery project has turned its focus to reckoning and repair. Recommendations include honoring enslaved people through memorialization, research, and curricula. “Partnering with Royall House and Slave Quarters represents one of the early ways Harvard is living up to commitments expressed in the report,” Bobo said.

Professor Tiya Miles and Kyera Singleton, executive director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford.

Over the years, feminist legal expert Janet Halley — who held the Law School’s Royall chair appointment from 2006 to 2022, resigning when the post was permanently retired — organized upwards of 20 tours to the Medford museum for students, faculty, and alumni.

“Nothing you can read replaces being in the place where this all went down,” she said. “The museum has been just an incredible partner in building awareness of this legacy.”

The historic site once operated in the spirit of “colonial-revival nostalgia,” as Halley once wrote, but it was transformed in recent decades. An archaeological dig commissioned in the late 1990s unearthed one of Singleton’s favorite objects, a game piece fashioned from tiles. It was found near the Slave Quarters, in an area out of view from the main house. “It allows us to think about ways in which enslaved people tried to circumvent surveillance,” said Singleton, who soon will earn her Ph.D. in American culture from the University of Michigan.

Tiya Miles, the Michael Garvey Professor of History and Radcliffe Alumnae Professor, first took students to the site in early 2020 for her “Slavery and Public History” course. This spring, she helped orchestrate multiple visits by students in an introductory humanities course, co-taught with urban studies expert Bruno Carvalho, a professor of Romance languages and literatures and African and African American studies who currently serves as interim director of the Mahindra Humanities Center.

“Students are often struck by the intimacy of slavery,” said Miles, who advocated for formalizing Harvard’s partnership with the museum. “When Singleton points out the pallet where enslaved people slept, they realize that right across the hall or perhaps even in the same room those who owned the individuals would have been sleeping in their beds.”

Later in the semester, the humanities class set about creating a digital walking tour that connects the Law School and the property with maps, text, visuals, and audio. One student will revise the tour assets over the summer before the final version is submitted to Singleton, the museum’s sole full-time employee.

Also working with the museum is Aabid Allibhai, a Ph.D. candidate in the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences studying African and African American studies, with a primary field in history. Allibhai is part of a research team put together by Singleton that is digging into the lives of those enslaved by the Royalls at sugar plantations in the Caribbean.

It’s imperative that the relationship is reciprocal, stressed Miles, who also serves as director of Harvard’s Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History. “When we descend upon a historic site — especially a small site with tiny staff — we are asking the people who run that site to help us to teach our students. We’re asking them to do a form of work. We have to reciprocate by working as well.”

For Miles’ students, the history lesson gets highly personal. As the class settled into the Royalls’ opulent bedroom — two steps from a stark storage area where some enslaved residents slept — Singleton was swept into a side conversation regarding the Royall family crest and its longtime ties with the Law School.

A sophomore shook his head. “That’s crazy,” he whispered. “Is that public knowledge?”

“Yes, it’s public knowledge,” replied Singleton, who recently was given a Warren Center fellowship as part of the new partnership. She directed him to the Legacy of Slavery report to learn more. Then she steered to another of the site’s former residents, a figure rising in esteem with a Law School courtyard, lecture series, and conference newly named in her honor.

Belinda Sutton, enslaved by the Royalls for some 50 years, filed a series of petitions with the Massachusetts General Court seeking a pension from the proceeds of Isaac Royall Jr.’s estate. In the first of these documents — dated February 1783, the year slavery was effectively abolished in Massachusetts — Sutton recalled being abducted from her homeland in Africa and enduring the Middle Passage. She also described laboring under the Royalls while being denied “one morsel of that immense wealth” she helped create.

“For me, ending on Belinda Sutton is really important,” Singleton told the students. Few documents exist from Black women in the 18th century, and Sutton cannily used the courts to leave behind her story. And, Singleton said, the pension was granted but never fully honored — a call for reparations still resonant today.