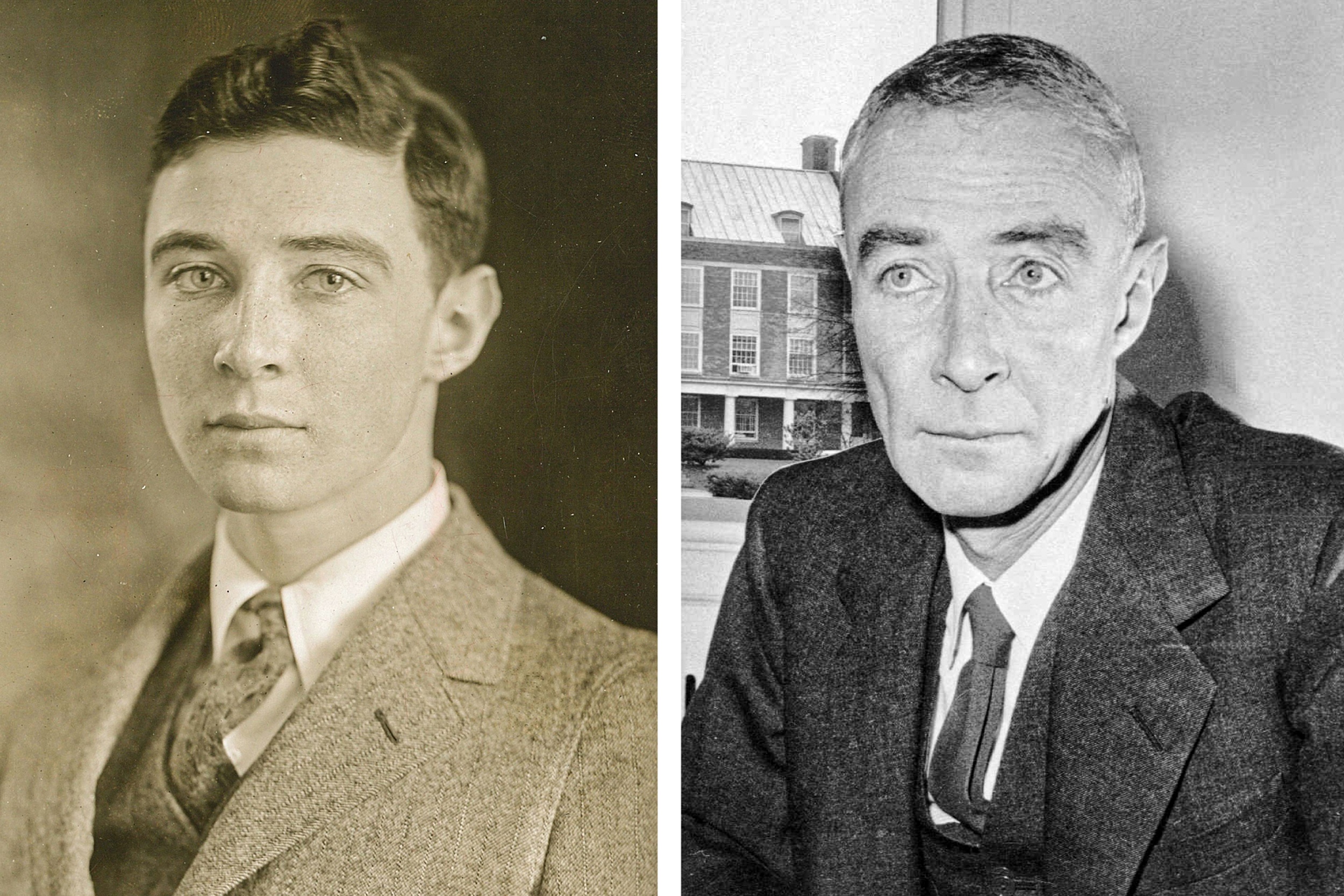

J. Robert Oppenheimer pictured in 1926 and in 1958.

Harvard University Archives; AP file photo

Closer look at ‘father of atomic bomb’

Historian unwinds the complexities of J. Robert Oppenheimer as scientist, legend

J. Robert Oppenheimer was a complicated man. A Harvard-educated theoretical physicist and scientific director of the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico during World War II, he is often referred to as the “father of the atomic bomb.” But he also had his federal security clearance revoked during the McCarthy era, a disputed decision that was only posthumously reversed last year. Questions had been raised about his associations with communists and, more importantly, his opposition to the development of the hydrogen bomb — he eventually would become a staunch proponent of nuclear arms control. Ahead of the release this week of the new biopic “Oppenheimer,” the Gazette spoke with Steven Shapin, the Franklin L. Ford Research Professor of the History of Science, to learn more about the man behind the charismatic character. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q&A: Steven Shapin

GAZETTE: Could you give a brief overview of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos?

SHAPIN: The Manhattan Project was the name given to the enterprise to build the atomic bomb, starting in the summer of 1942, and culminating in the dropping of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs in August 1945. The project took its name from the Manhattan Engineer District in New York; it was run by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and directed by Gen. Leslie Groves.

It’s been called the biggest technoscience project in the history of the world: over $2 billion at the time. The Manhattan Project is often identified with Los Alamos, the design center in New Mexico, but it’s important to appreciate that it was a truly enormous nationwide effort. The Manhattan Project is the name collectively given to all the installations involved in designing and assembling the atomic bomb, of which Los Alamos would be the nerve center, and also to the vast plants for the separation of U-235 (at Oak Ridge, Tennessee) and for the production of plutonium (at Hanford, Washington).

GAZETTE: What was unique about Los Alamos that allowed scientists — like Oppenheimer — to come together to develop such advanced technology?

SHAPIN: Virtually everything about it was unique. At Los Alamos, the bringing together of some of the world’s greatest talent — not just in physics, but also in computation, mathematics, metallurgy, chemistry, and many sorts of engineering — was unprecedented. “Everybody who was anybody” was there — including many Nobel Prize winners.

Another thing that was unique about it was that it was a military installation, but one including a great scientific research center. And that assembling of scientific talent for military purposes had never happened before — certainly not remotely at that scale. There were a lot of tensions associated with the relations between science and the military; military conceptions of secrecy and security often clashed with scientific expectations of relatively free communication. There were no obvious off-the-shelf patterns for this kind of scientific collaboration and organization, so neither the scientists nor the military had secure understandings of what sort of place Los Alamos was.

For the scientists, there was enormous time pressure, because they understood that this bomb had to be built to beat the Germans to it. The complexity of the task was enormous, but the resources were also enormous.

“We have used the figure of Oppenheimer as a way to think about science and morality, science and politics, science and religion, science and philosophy, about the role of the intellectual in modern society.”

GAZETTE: A lot of people credited the success of building the bomb to aspects of Oppenheimer’s unique personality, which you refer to as “charismatic authority” in a 2000 paper you wrote with Charles Thorpe. Could you talk a little more about him and what he was like as a person and a leader?

SHAPIN: Oppenheimer was actually a very unlikely choice for the scientific directorship of Los Alamos. Many people thought that he lacked any organizational ability or much sense of how to manage people. One of his colleagues once said that he couldn’t run a hamburger stand. And yet he did successfully run Los Alamos. And many people said afterwards that he was the essential person in the project — his role in organizing people and motivating people and in bridging the world between the scientists and military was absolutely key. I like the British saying “Cometh the hour, cometh the man.”

Oppenheimer was recognized as a charismatic leader, but lots of people helped him become a successful leader, and a charismatic one. This unique individual was a collective accomplishment. That said, Oppenheimer was only one of hundreds of thousands of people working on the project. He did not have much to do with the production of fissile materials, without which there would have been no bomb. He did not have great understanding of the mathematics of calculating shock waves or of engineering explosive lenses. And of course, he did not decide how the bomb would be used.

I suspect that Oppenheimer is such a compelling character because he’s so enigmatic, so complicated. We have off-the-shelf conceptions of eccentric scientific genius. Oppenheimer fits that mold pretty well. In contrast, Gen. Groves didn’t look like, and didn’t act like, our conceptions of scientific genius — but there’s a case to be made that his experience with very large-scale engineering projects made his role central to the project’s success. If there has to be a single “father of the bomb,” why not Groves? But would a movie called “Groves” be as attractive? Doubtful.

GAZETTE: One of the ways people described Oppenheimer was that at times he had an almost spiritual presence. How did that affect people’s deference to him and his ability to lead?

SHAPIN: Some Los Alamos scientists were moved by this presentation of spirituality, of moral vision, and of cultural breadth. Other scientists thought it was a bit too much, that Oppenheimer was something of a show-off. He famously said that when the Trinity test bomb exploded, he remembered a line from the Hindu sacred text the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Other people reported that what he actually said was something more mundane — something along the lines of: “It worked.”

I understand that actor Cillian Murphy lost a lot of weight to portray Oppenheimer; people did reflect on how thin Oppenheimer was, how much weight he had lost during the project — partly through illness, but partly also through anxiety and the tremendous weight of responsibility. Some scientists at Los Alamos recognized in Oppenheimer’s thinness a religiously toned ascetic ideal. He had, they said, almost no flesh to him; he was all mind, all spirit.

GAZETTE: There was a lot of uncertainty in the project, especially in terms of leadership and who was managing which aspects. How did Oppenheimer help address some of those things?

SHAPIN: This story is often told too simply: “The military wants secrecy; the scientists want openness.” The truth of matter is there’s never totally been open communication in science, and many scientists were comfortable with military types of secrecy, especially in an enterprise of this strategic importance. But one of the things that Oppenheimer did was to advocate for weekly colloquia in which people in different divisions actually got to talk to each other, and he had to persuade Groves that the project could not be successful if scientists working in different areas were compartmentalized, only knowing what they specifically needed to know. Oppenheimer was right to think the communication of people with different skill sets, addressing different parts of the project, was necessary. And he did much to make that happen.

“He had, they said, almost no flesh to him; he was all mind, all spirit.”

GAZETTE: As Oppenheimer and the whole team of scientists were developing the bomb, were they aware of how it was going to be used?

SHAPIN: Until the defeat of Nazi Germany — or really until intelligence missions established shortly before that there was no crash program to build an atomic bomb in Germany — until that point, they were totally committed to building the bomb, because the purpose was to prevent the Germans from having sole possession of this weapon. Until that point, Los Alamos scientists were not thinking hard about what to do with this weapon — whether it would be used against Germany or whether the threat of its use would be enough. It was an enormously challenging scientific and technological problem, and they were fully engaged in making that project a success. So the moral and political agonizing about the bomb and what to do with it belongs to a brief period toward the end of the project and it involved a relatively small number of people.

After the defeat of Nazi Germany, some of the project scientists thought that there was no need to drop the bomb on Japan, that there might be an off-shore demonstration, or that Japan might be clearly told that the bomb existed and what it could do, but Oppenheimer did little or nothing to help them. Nor is it clear that Oppenheimer could have done much to influence the use of the bomb. He had scientific authority but no significant political power. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were military and political decisions. And it is clear — despite the agonizing — that many leading scientists wanted to see not just whether the bomb worked — the Trinity test established that it did — but what it could achieve as a strategic weapon. I think it’s fair to say that there were degrees of ambivalence in Oppenheimer’s own attitude.

GAZETTE: Do you feel that Oppenheimer’s leadership was ultimately what brought about the atom bomb?

SHAPIN: No, I don’t — not because Oppenheimer didn’t and someone else did, but because you can’t sensibly talk about a project of this complexity and size and ascribe its success to an individual. I think that’s a point of principle. You might sensibly say that forms of industrial organization and huge expenditures of money built the bomb. But no one is going to see that movie. Forms of industrial organization don’t have steely blue eyes or charisma or moral anxiety.

GAZETTE: So what is Oppenheimer’s legacy to the scientific community?

SHAPIN: That’s an interesting point. Oppenheimer did not have a Nobel Prize; other project physicists did. After the war, he wrote only a few scientific papers. If he had not been scientific director at Los Alamos, would Oppenheimer have had a Nobel Prize-winning career in physics? Possibly not. Would many biographies have been written about him? Probably not. Would he have had a platform as a post-war cultural commentator and would his views have been listened to? Possibly not. Would we all be going to see a movie about the man? Certainly not. Gen. Groves could easily have selected someone else to be scientific director of Los Alamos. If he had, what would Oppenheimer have become? What, if anything, would we be thinking about him?

GAZETTE: Some people loved him. Some people hated him. What do you think, given what you’ve learned about him over the years?

SHAPIN: I think great scientific leaders, like great political leaders, are made partly by what they bring to the table and partly by circumstance. We tend to overvalue the role of innate individuality and undervalue the role of accident, circumstance, and, especially, of other people in making what we regard as a unique personality. Still, accident, circumstance, dramatic conventions, the work of historians, and many other considerations have, over the years, surrounded Oppenheimer with an aura, and made him fascinating. That’s a fact about Oppenheimer, but also a fact about us. We have used the figure of Oppenheimer as a way to think about science and morality, science and politics, science and religion, science and philosophy, about the role of the intellectual in modern society. He’s become an icon. And, if not him, who else would it be?