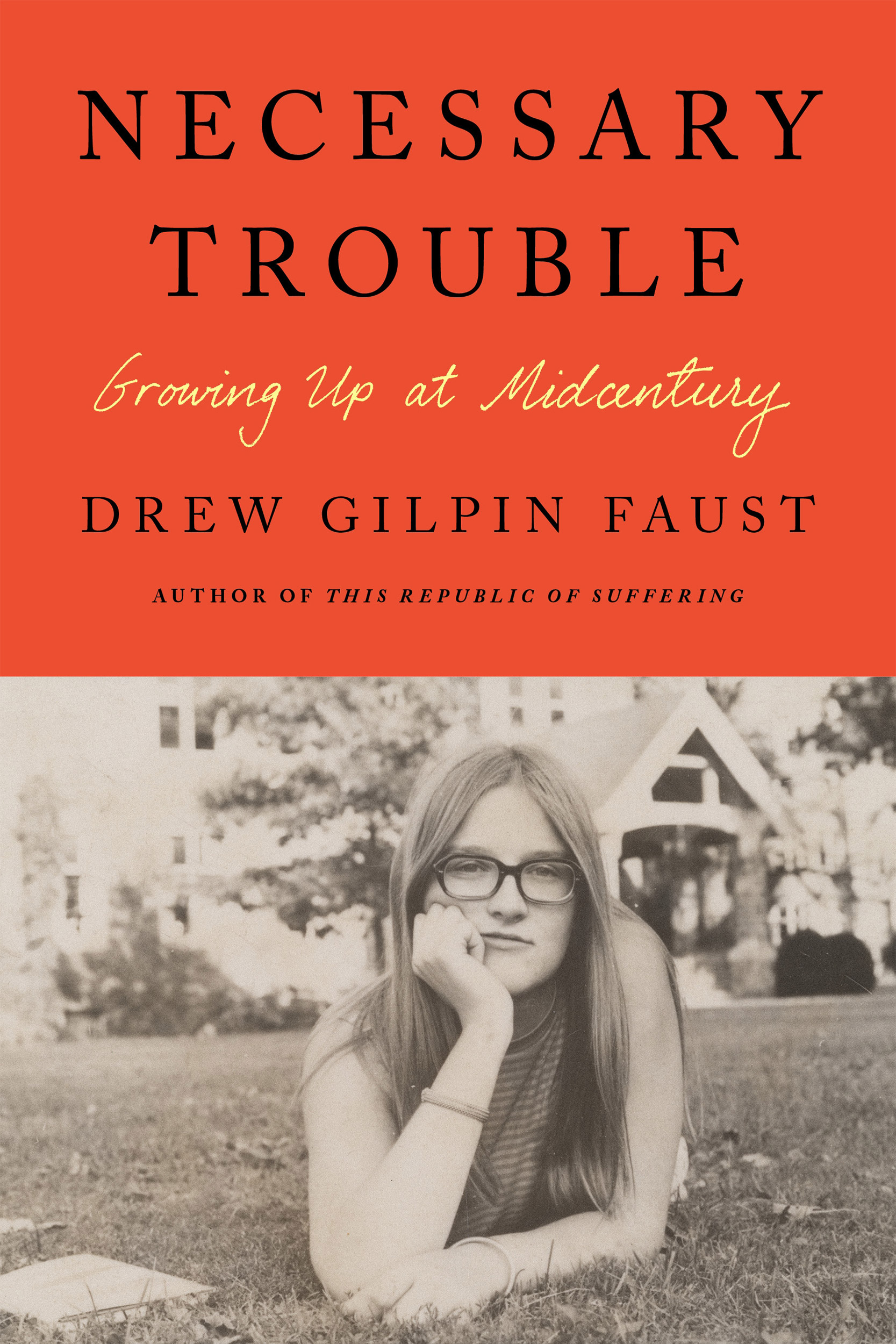

A detail from the cover of “Necessary Trouble: Growing Up at Midcentury” by Drew Gilpin Faust.

‘What you can do for your country’

Future Harvard president leaves Virginia for Concord Academy, set on path by JFK inauguration speech, visit by MLK

Adapted and edited for length from “Necessary Trouble: Growing Up at Midcentury” by Drew Gilpin Faust, president emerita and Arthur Kingsley Porter University Research Professor

I left Virginia for New England to become a boarding student at Concord Academy three days before my 13th birthday. The school occupied a row of picturesque late 18th- and early 19th-century clapboard houses that stretched along the town’s Main Street. Behind them, a few other buildings dotted a campus that stretched down to the Sudbury River. It looked like an illustration for “Little Women,” which had been written just across town less than a century before.

Concord was something of an unusual school in the early 1960s. All girls and less than four decades old, it did not have the history or the financial resources of some of its more established sisters — Miss Porter’s or Emma Willard or St. Timothy’s — not to mention its venerable and richly funded male counterparts, schools like Groton, Andover, Exeter, or St. Paul’s. And it differed from them in philosophy as well. “This is not a ‘strict’ school,” the headmistress, Elizabeth Hall, explained to students, “but it is a hard school … It is hard because finding out for yourself is far more difficult than following directions … It is hard because you are forced to meet yourself face to face … Rules would have given you an escape from thinking.”

Compared with other girls’ schools of the era, Concord gave us enormous freedom. We could go into town — a few minutes’ walk away — any afternoon after classes; we could take a bus to Cambridge or Boston on Saturdays or Sundays or spend weekends away from campus whenever we liked, as long as our grades were acceptable. This was not the norm at most boarding schools, for girls or boys. One of my contemporaries remembers how her brother was “locked up” at Groton, while she roamed “free” at Concord. “They trusted us,” she recalled.

More like this

For me, the sense of liberation was almost overwhelming. I was no longer isolated on a farm, but once again in a New England village like the one I had relished during the summers with my grandparents. And, like Scout from “To Kill A Mockingbird” or Nancy Drew, I no longer had a mother scrutinizing and, as I perceived it, criticizing my every move. I was in a school where girls were what mattered, and where their intellects were reinforced and rewarded. I wrote a letter to my parents about once a week, and I would take my turn on the phone in the hall of the dormitory to call once or twice a month. From that time onward, my parents knew and understood little of my life. For the most part, it was not that I intentionally hid or kept things from them. It was that they had become almost irrelevant; they represented a constraint I had to manage and sometimes resist, but no longer the same challenge or looming emotional force.

But Concord was not without its own complexities and contradictions, and many of these were embodied in the personage of its extraordinary headmistress. Mrs. Hall had run the school for more than a decade when I arrived and was credited not only with doubling Concord’s size but also with having transformed it from mostly a local day school into one with a national reputation. Yet Mrs. Hall put on no airs. She often referred to herself not as headmistress, but as “Head Mischief,” an example of the gently self-mocking approach to life she called being “simply true.” It was the same outlook that led her to request we sing “Nearer My God to Thee” to her every year on her birthday. Even a half century later, my schoolmates speak of the impact she had on their lives. At a time when most of us came from families in which women did not pursue careers, here was a woman of such commanding presence and professional accomplishment that we were at once intimidated and entranced.

***

And yet. She was no revolutionary and very much the product of her background and her time. Her father had been enormously rich — a “Wizard of Wall Street” — and she took for granted both her privilege and ours. She assumed we would never need to worry about making a living and would always enjoy material prosperity. “You, who are possessed of much,” she addressed us as she urged a noblesse oblige founded in a sharp sense of social hierarchy. “Much more is expected of us than is expected of others.”

She embraced hierarchies of gender as well. “Ladies, be ladies,” she exhorted us, even as she drove a tractor, dismantled a building, ran a school, and held everyone around her in her thrall. She admitted to having been a committed tomboy and having bridled at such demands. Finally, she was sent away to school by her parents “to acquire more conventional graces.” She acknowledged that to ask us to be ladies might sound like asking a girl to impersonate her great-grandmother. But the archaic term, she continued, connoted “womanly excellence,” the fullest realization of our feminine selves, to which we should all aspire. A woman’s femininity, she explained, “is proven by her willingness to sacrifice personal advancement on behalf of making the labor of man meaningful in terms of his noblest aims.” What she told us in her beloved chapel and assembly talks seems from today’s vantage point completely at odds with what we saw her doing before our eyes. “I do not think women are the equals of men,” she baldly declared; in her view they were complementary. The struggle for political equality, she believed, had “forced the exaggerated claim that women were equal to men in every way and therefore should have every possible equality of opportunity and privilege.” To have them compete would be, as she put it, “as ridiculous as it would be to put the wind instruments of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in competition to see which could produce the loudest music, or get first to the end of the score.”

Because men and women occupied different places in the world, this meant in her view that very few women would or should expect to pursue careers. It makes me sad these many years later to read words I must have heard long ago as her prescription for a woman’s life. She expected us, she said, “to have the humility to accept the fact that it will be given to very few of us to accomplish anything in our lives to which we can refer as a measure of our success. This is … especially true of women, for most of whom the luxury of defining a specific accomplishment is over when they complete their formal education … From then on, for most of us, life is an unending series of small tasks, usually well within our means to accomplish, and of continual interruptions.” Did she really mean that? Was that all we could expect from the future? What did we do with such advice from one we respected so deeply?

She failed at teaching us to be resigned to lives characterized by unending series of small tasks, and I suspect that on some level she intended to. “All of us have an overwhelming need to feel that our lives amount to something,” she continued just a few phrases later.

***

On Jan. 20, 1961, my biology class was permitted to skip science for the day. We crowded instead into a housemother’s apartment to watch John F. Kennedy’s inauguration on her little black-and-white television. I remember an elderly, white-haired Robert Frost blinded and bedazzled by the reflection of the winter sun off the newly fallen snow, unable to read the poem he had composed for the occasion and reciting another from memory instead. And I remember the young president exhorting a new generation in a language of duty and responsibility. I heard his words as in many ways only a more rhetorically powerful version of messages we were used to receiving on a regular basis at the school. “Ask not” what can be done for you, but what you can and must do for others. The world was waiting for us to make it better.

Our own little world at Concord could have benefited from more rigorous scrutiny. I reveled in this new environment of intellectual rigor, openness, and challenge, of empowered females and high expectations. But the school was overwhelmingly homogeneous; it was essentially a community of well-off white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. My favorite history teacher could, 60 years later, list by name the Jews at the school during our time there — he and one other teacher, fewer than a handful of students. And I was living as well in a world even more racially segregated than the one I had left in Virginia. Segregated de facto rather than de jure, to be sure, which reinforced a certain moral complacency on the issue. Concord had not a single Black student until my senior year and no Black faculty or staff. The school was not especially unusual in this regard. Andover and Exeter — large, rich in scholarship funds, and cosmopolitan in outlook — had admitted a few Black students since the mid-19th century, but the smaller boarding schools were more like Concord. Middlesex, Milton, Miss Porter’s, and St. George’s had no Black students in the fall of 1960. My brother Tys, who would graduate from St. Paul’s the following spring, had no Black — or Jewish or Catholic — classmates and went on to Princeton, where only one member of his class of 1965 was African American.

As the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum in the early years of the 1960s, a few of us at Concord began to press to integrate the school and to push for more Black visitors to campus. But this was not yet anything like an era of student activism or student demands. We asked respectful questions and initiated polite discussions with our teachers and school administrators. We were pleased when at last one Black student arrived on campus in the fall of 1963 and when the following spring the Reverend John T. Walker, the first Black teacher at St. Paul’s and later the Protestant Episcopal Bishop of Washington, a champion of social and racial justice, was invited to be our commencement speaker. Students greeted these changes with enthusiasm and perhaps a bit of over-solicitousness. When I learned that a Black student would be enrolling my senior fall, I asked if I could room with her but was told that assigning her to the president of the senior class might seem to focus too much attention on her arrival. Concord would be no Little Rock.

I was in the North, living in a town that had, a little more than a century before, been a stronghold of antislavery sentiment. The Concord residents Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau became outspoken opponents of human bondage, and the revolutionary John Brown relied on the town for financial support for his raids in Kansas and his ill-fated 1859 effort to raise a slave rebellion at Harpers Ferry. A Concord schoolmaster was seized by federal marshals as one of Brown’s “Secret Six” co-conspirators and rescued only when 150 townspeople rushed to his defense. Yet the flame of racial justice seemed to have flickered in the subsequent century. By custom and economic circumstance, 20th-century Concord Academy was as segregated as the Virginia community in which I had grown up. But there was an important contrast. Although an ideology of racial difference and white superiority might well have lived somewhere deep within the hearts and minds of those around me, I never heard it articulated or justified. In fact, the opposite was true. We earnestly discussed “To Kill a Mockingbird” with our English teacher; we read of the violence against the Freedom Riders with horror and anger; and like so many other white Americans, we began to look on Martin Luther King Jr. as an American hero. This gap between rhetoric and reality might justly be seen as rank hypocrisy. But it was neither blindness nor denial. And it also proved a foundation for change and possibility.

In February 1963, the headmaster of Groton School, John Crocker, extended an invitation to Concord Academy. An Episcopal minister, Crocker had long been dedicated to Civil Rights and had admitted the first Black student to Groton in 1952. He had come to know King during his years as a graduate student at Boston University and had persuaded him to spend two days at Groton, meeting with students and delivering a speech at an event that would include guests from nearby schools. We were told we could sign up if we were interested. On a cold winter night, a yellow school bus carrying about 20 Concord students drove the hour to Groton. It was six weeks before King would be jailed in Birmingham; it was six months before the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the “I Have a Dream” speech, and two years before the Selma march. Yet in my eyes he was already a Great Man.

He was also a great orator. In his address to this gathering of students, King spoke more as the scholar than as the Black preacher who would rivet the crowd in Washington the following August. He cited anthropologists, philosophers, Shakespeare, John Donne, and the Bible. He educated us about the structure of syllogisms and the variety of Greek words for love. But the cadences of his speech, the poetry of his words, and the moral force of both the message and the man carried an emotional power that was captivating.

“America is essentially a dream,” King began, but “a dream yet unfulfilled.” He confronted us with the “sublime words” of the Declaration of Independence and the “strange paradoxes” of institutions like slavery and segregation that defied them. Throughout the speech, he repeated his call for “people of good will” to make the American dream a reality. He spoke of colonialism and its imminent end and urged us to take a world perspective on justice, not just because it was necessary to defeat communism but because it was right. He challenged the notion that there were superior and inferior races, insisting that different life outcomes were the results of differences of circumstance. He offered examples of accomplished “individuals in the Negro community” like Marian Anderson, George Washington Carver, Ralph Bunche, and Booker T. Washington as evidence of Black capacity. And he called for legislation and nonviolent direct action as necessary means to achieve justice and equality. He attacked what he called the “myth of time.” Insisting that patience would yield change, he argued, would delay progress for decades if not centuries. Nor would education in and of itself solve the problem of racial injustice. Laws were necessary; they might not “change the heart but they could restrain the heartless.” And the Gandhian method of nonviolent direct action could work on the conscience of the oppressor to compel genuine transformation. Moral ends must be pursued through moral means. Racial injustice, he reminded his Massachusetts audience, was not confined to one part of the country; housing and job discrimination flourished in the North just as segregation did in the South. This was a struggle to “save the soul of our nation,” which was profoundly threatened by the “appalling silence of good people.”

King’s talk was well calibrated for his young and idealistic audience. We recognized ourselves in his words — complacent residents of a region that did not feel the urgency of Georgia or Alabama. We wanted to see ourselves as among the “good people,” but we had to recognize what had up to now been our “appalling silence.” In less than an hour, King had not only explained the political, philosophical, and religious foundations of the Civil Rights Movement but also charged us to join him. Here was a powerful response to John F. Kennedy’s question, a compelling answer to the question of “what you can do for your country.”

Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2023 by Drew Gilpin Faust. All rights reserved.