Lost in fictional maps

Fantasy worlds from Middle Earth to Westeros come to life in Harvard Library exhibit

How far is the Wicked Witch of the West’s castle from the heart of Emerald City? Or the Shire to Mordor? Luckily, a display at Harvard’s Pusey Library takes the guesswork out of planning your next fantastical trip through Middle Earth.

“From Academieland to Zelda,” on view in the library’s first-floor corridor through Nov. 3, features fictional maps that chart everything from TV, film, and literary locales to video game worlds, and even abstract concepts.

Calling the exhibition “kind of a mishmash,” curator Bonnie Burns, head of geospatial resources at the Harvard Map Collection, said that “within the exhibit you have maps that are kind of theoretical, like nursery rhymes and Fairyland maps. And then there’s a big chunk of maps of literature — Middle Earth to Narnia.”

A visitor takes in the exhibit on the first floor corridor of Pusey Library.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The nearly 30 maps on display span centuries. The oldest, the “Accurate Map of Utopia” by German cartographer Johann Baptist Homann, dates to 1720. The satirical paradise includes depictions of regions named Kingdom of Drinkers, Empire of the Fat Stomachs, and the Kingdom of Extravagance.

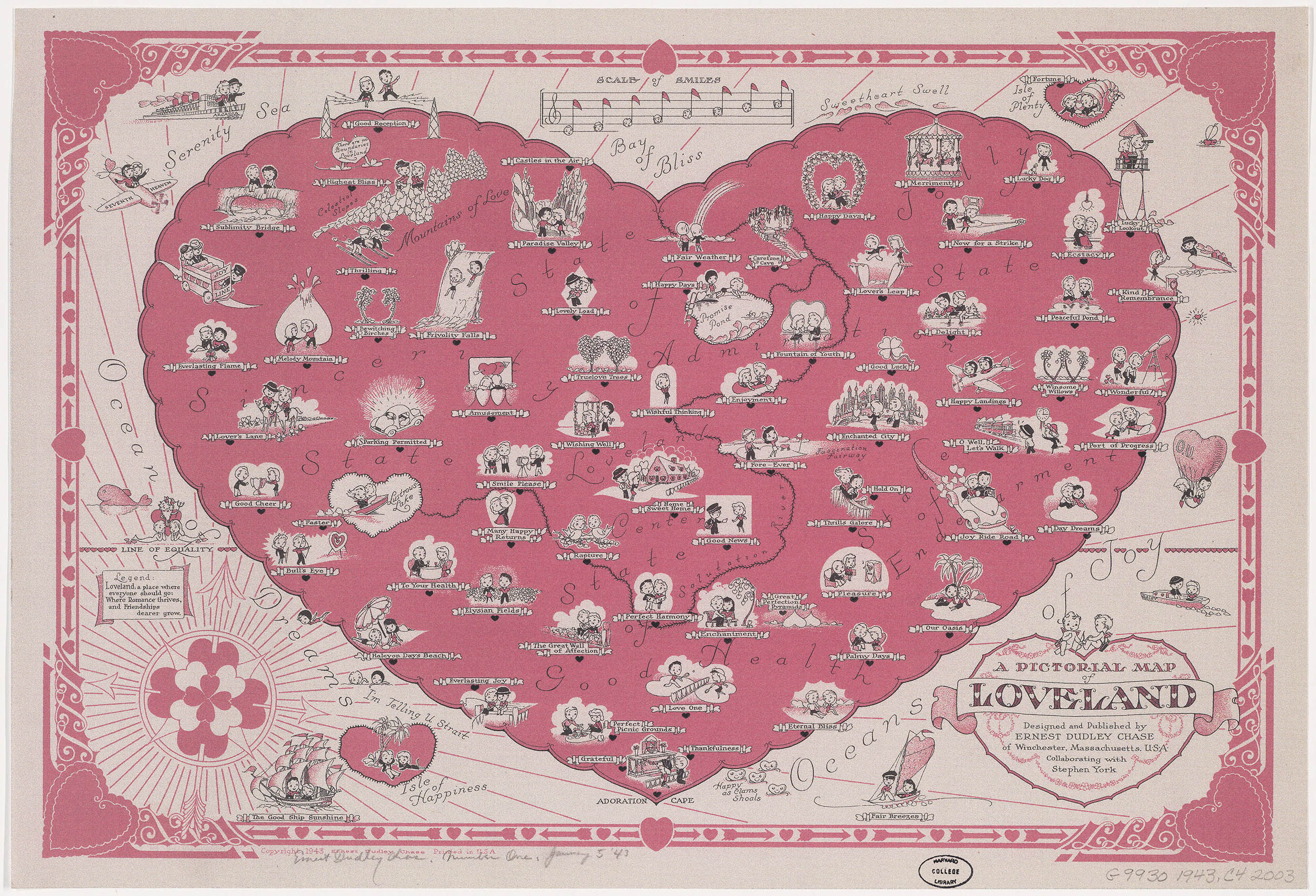

“A Pictorial Map of Loveland,” Ernest Dudley Chase, 1943.

Courtesy of Harvard Library

Two maps from 1943 and 1772 offer contrasting takes on love and marriage. “A Pictorial Map of Loveland” created by American greeting card illustrator Ernest Dudley Chase includes landmarks like Lustrous Lake, Happy as Clams Shoals, and the Serenity Sea. “A New Map of the Land of Matrimony” by Joseph Johnson and J. Ellis, however, tells a different tale with its Straits of Uncertainty, Languish Island, and ultimately, Divorce Island.

“It’s just so interesting to me to see how the written word, or even an idea like love, gets put together, and the thought process that goes into translating from an idea or a book into a map of all things,” Burns said. “And plus, they’re just really cool.”

Harvard University

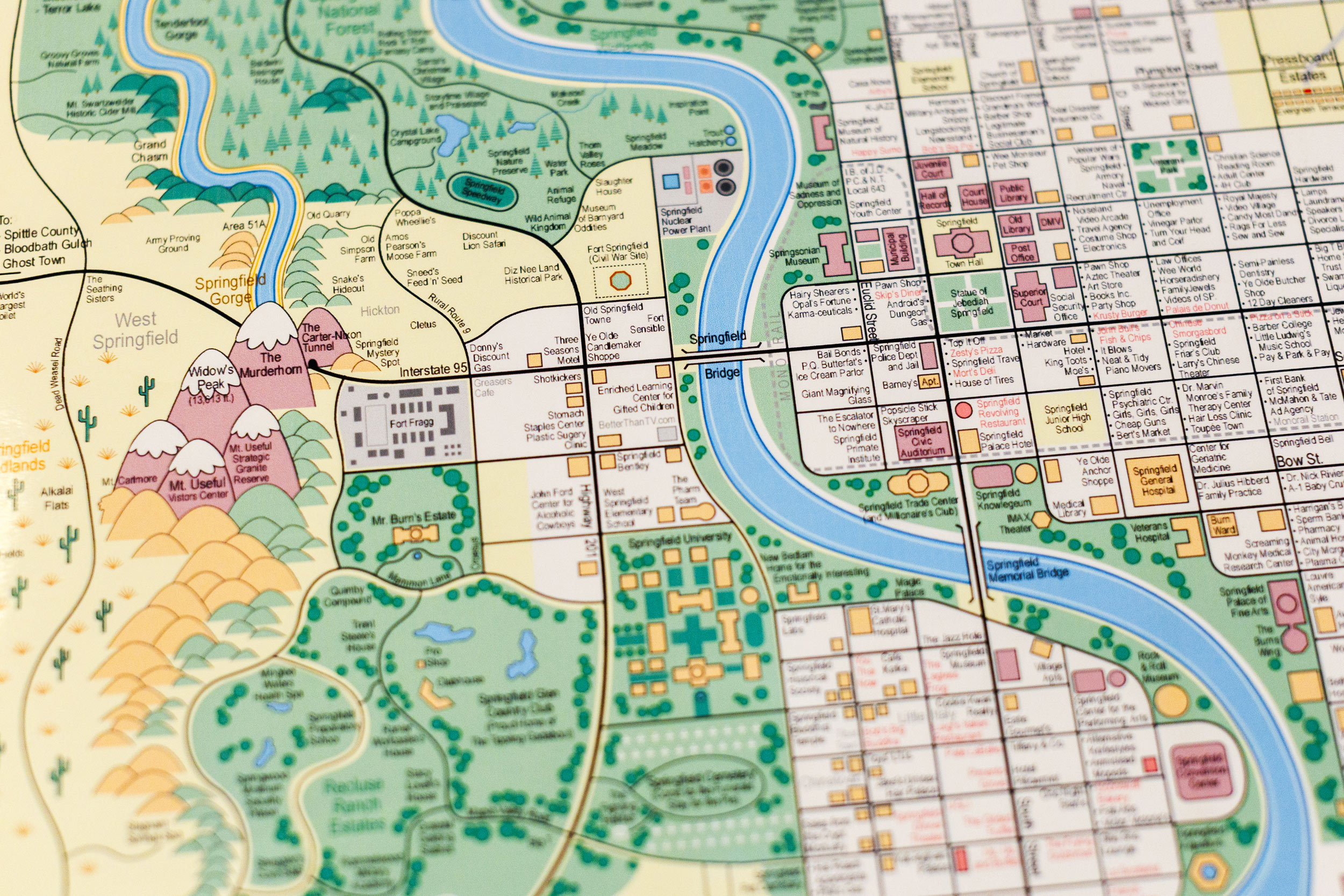

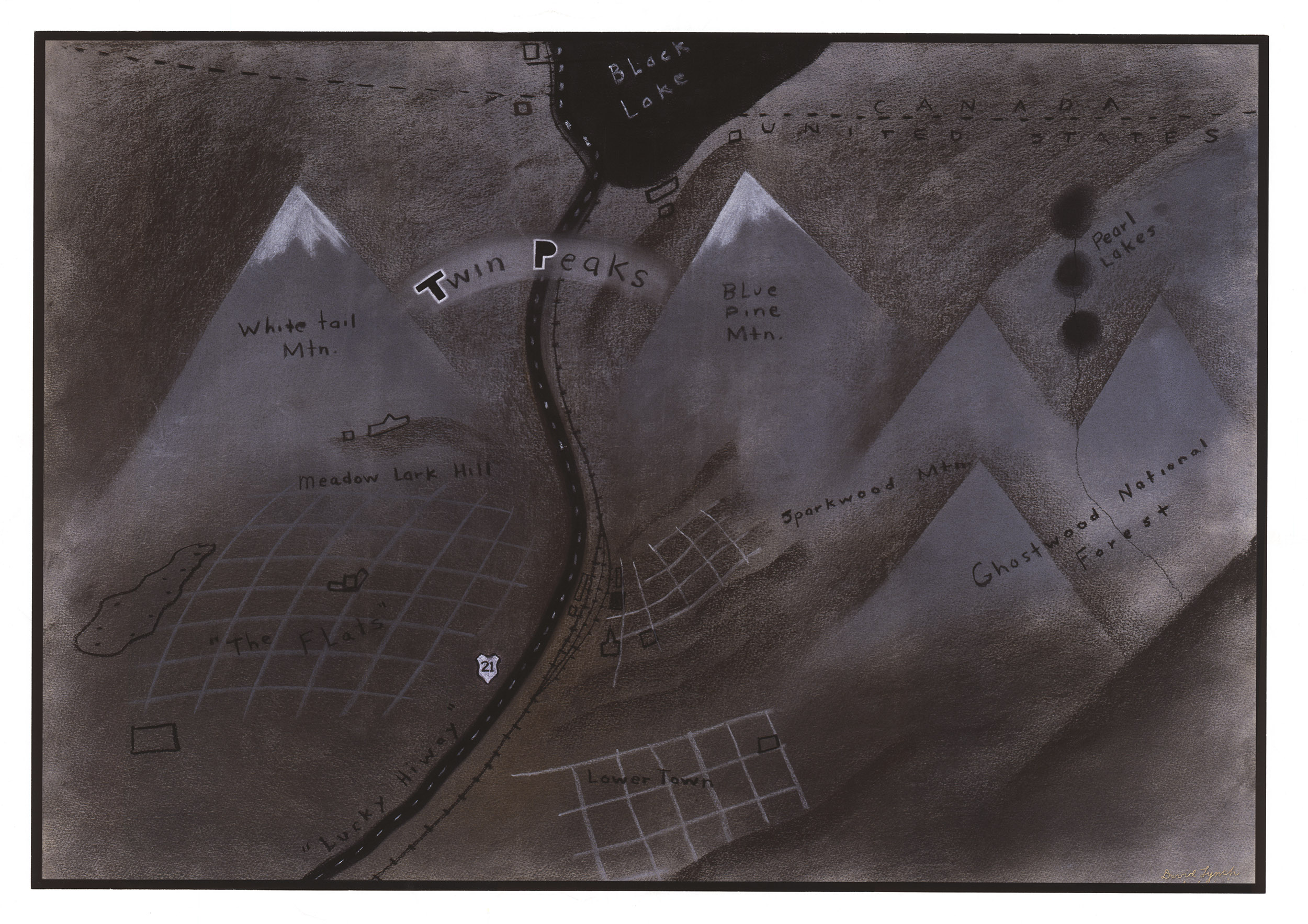

See “Simpsons” landmarks from the nuclear plant where Homer works to Duff Stadium, home of the Isotopies in “Guide to Springfield, USA.” A charcoal sketch by David Lynch used in a pitch to ABC for the “Twin Peaks” series evokes the mood of the town.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer; courtesy of Harvard Library

She added that some pieces in the exhibit are inspired by her own inclinations — a soft spot for the Zelda universe, or her child’s favorite fantasy series.

“Not everybody thinks in maps, but it can help you to understand the story, help you to understand a concept,” she said. “If you have that kind of spatial brain, it can really do a lot to bring the story even more to life for you. Because I’m that person, I’m always looking for them at the beginning of a story. And if it’s not there, I’m disappointed.”

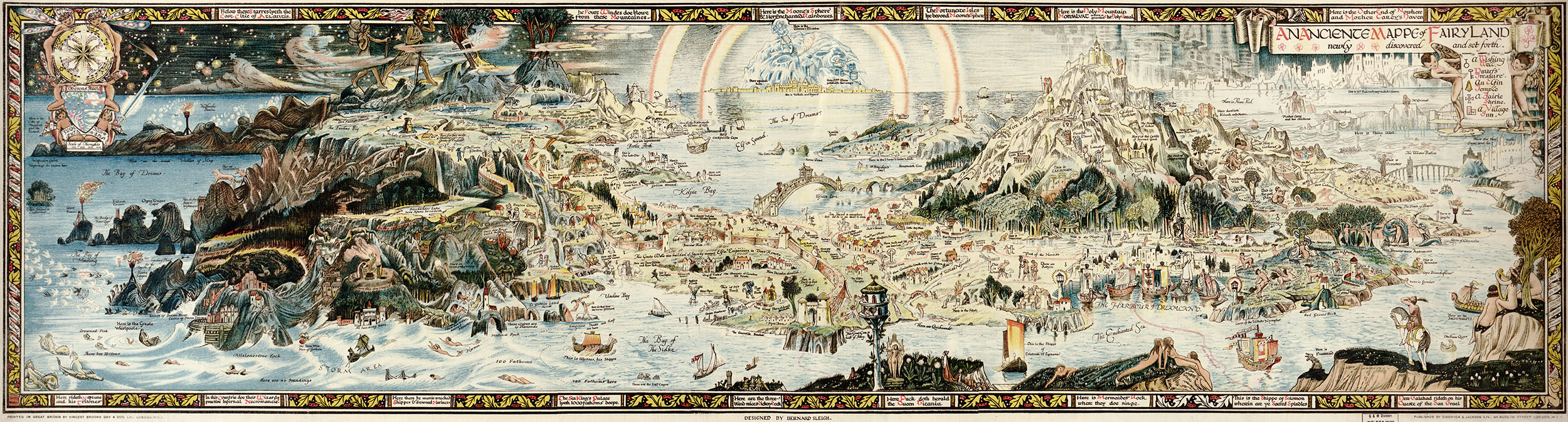

This 1918 map of “Fairyland” by Bernard Sleigh mixes Greek mythology, the works of Homer, and nursery rhymes.

Courtesy of Harvard Library

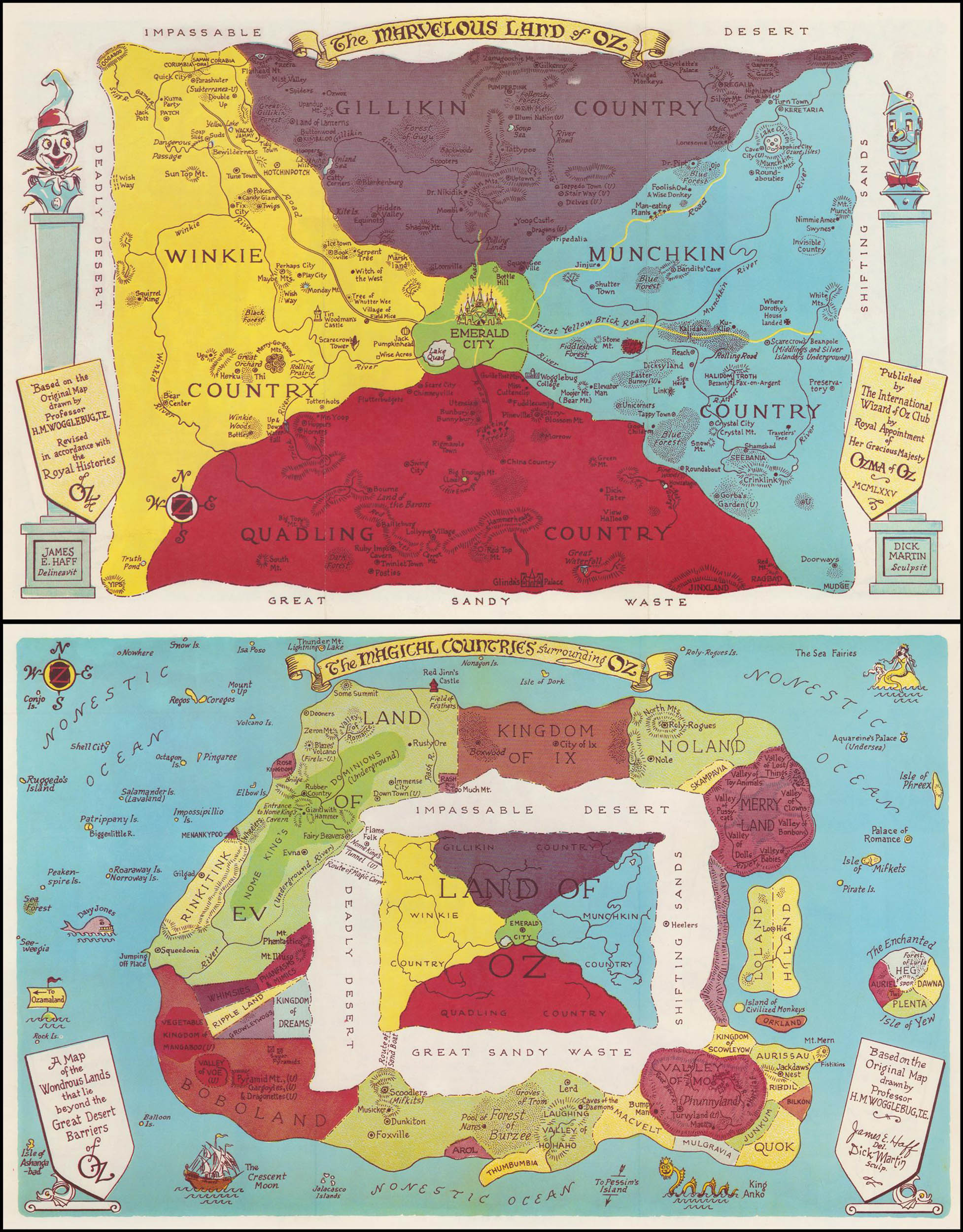

To those who just know the first book and the 1939 movie of “The Wizard of Oz,” only a small portion of the top map will seem familiar. Both maps taken together show the full geography of the 14 books in the Oz series.

Courtesy of Harvard Library

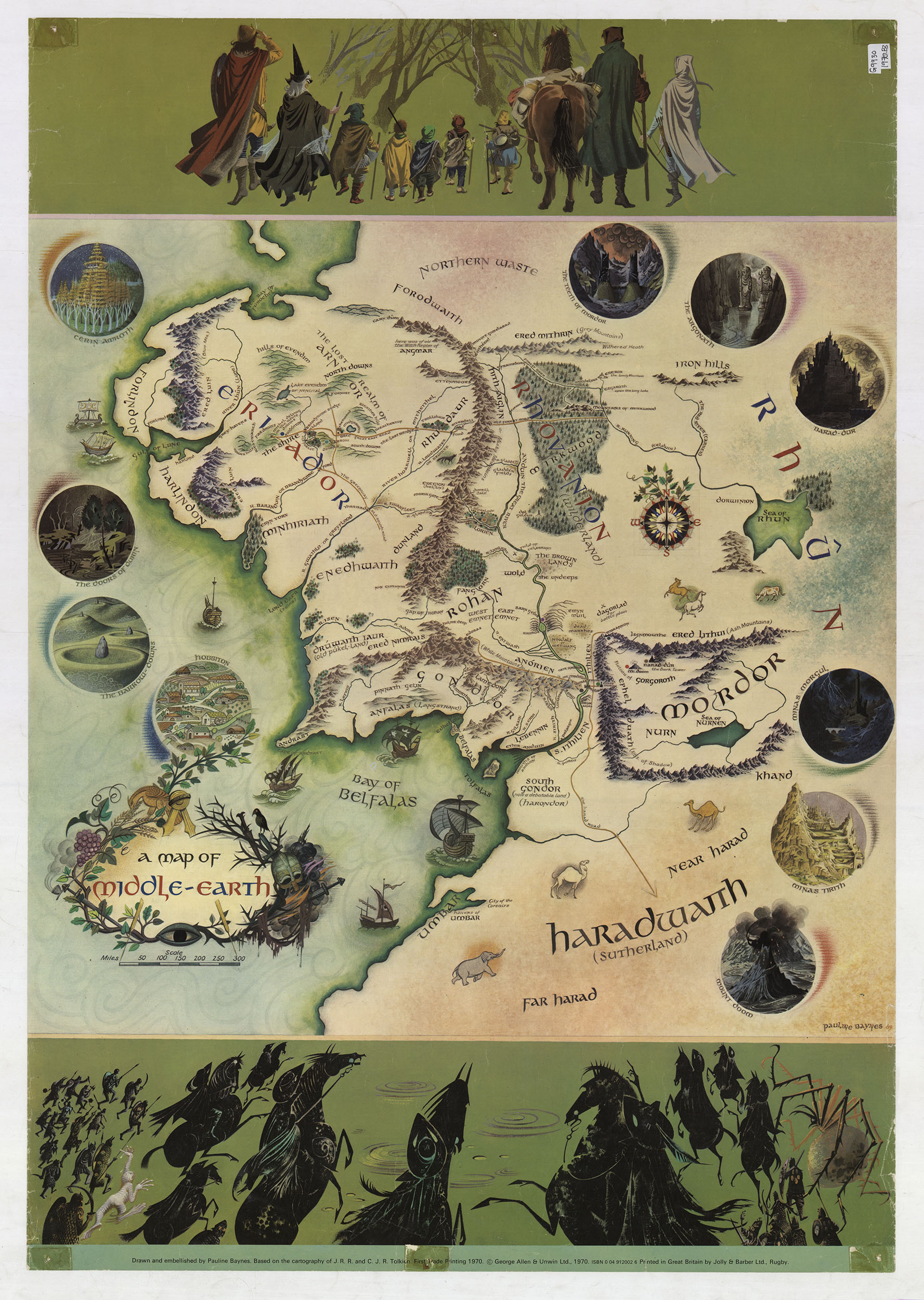

One place, two different maps for two different goals. J.R.R. Tolkien was quite involved in the creation of the first map pictured here of Middle Earth by Pauline Baynes in 1970. Although the other map, created by Daniel Reeves in 2012 for the memorabilia market, has a different look and feel, the geography is almost exactly as it appears on the Baynes map.

Courtesy of Harvard Library

“The Internet,” by Martin Vargic in 2014 provides a fascinating look at the internet from nearly a decade ago. Twitter is tiny, MySpace is hanging on at the edge. Zoom is nowhere to be found.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

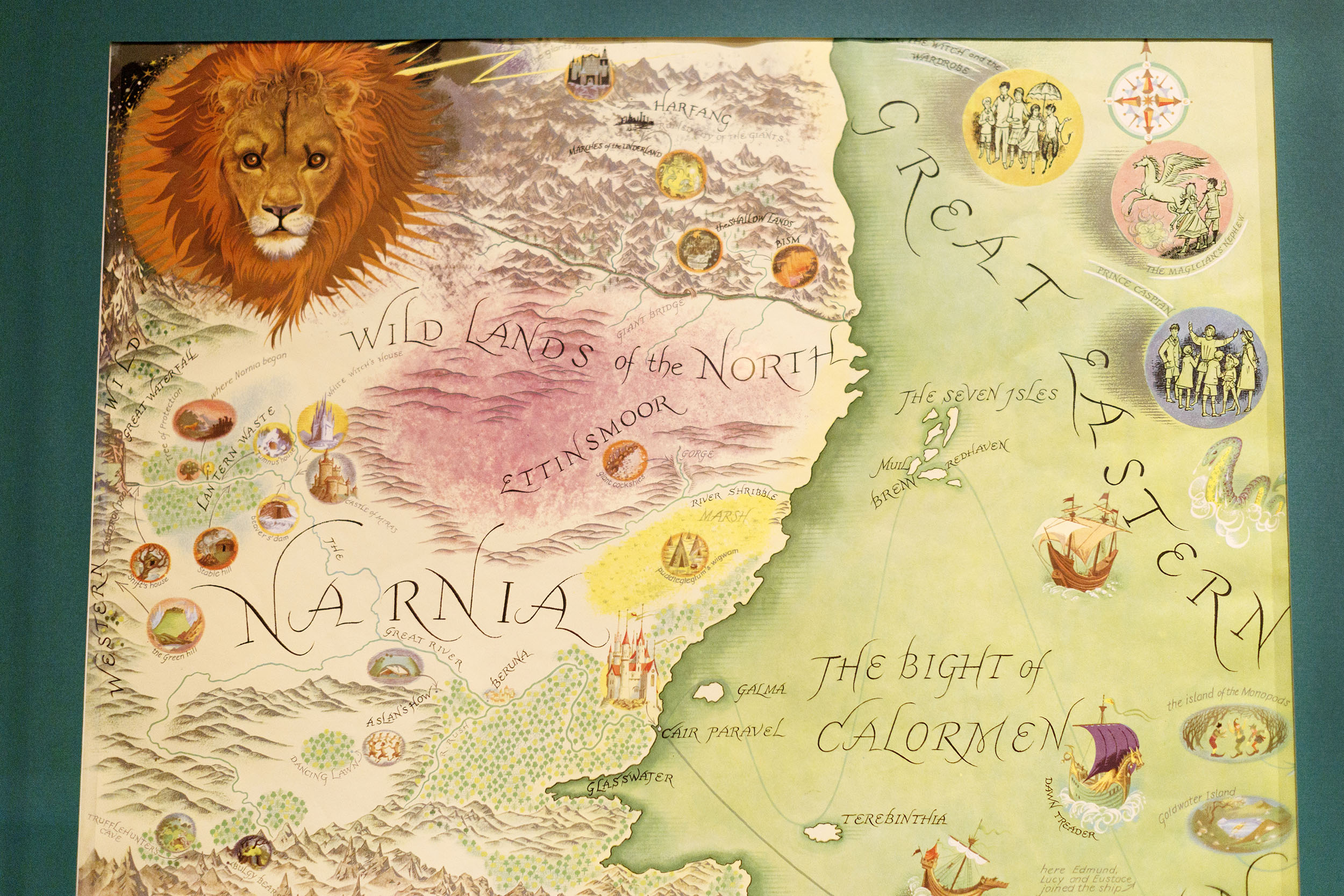

Pauline Baynes, who illustrated all of the “Narnia” books, attempts in this poster to capture the geography of the entire series in a single image.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

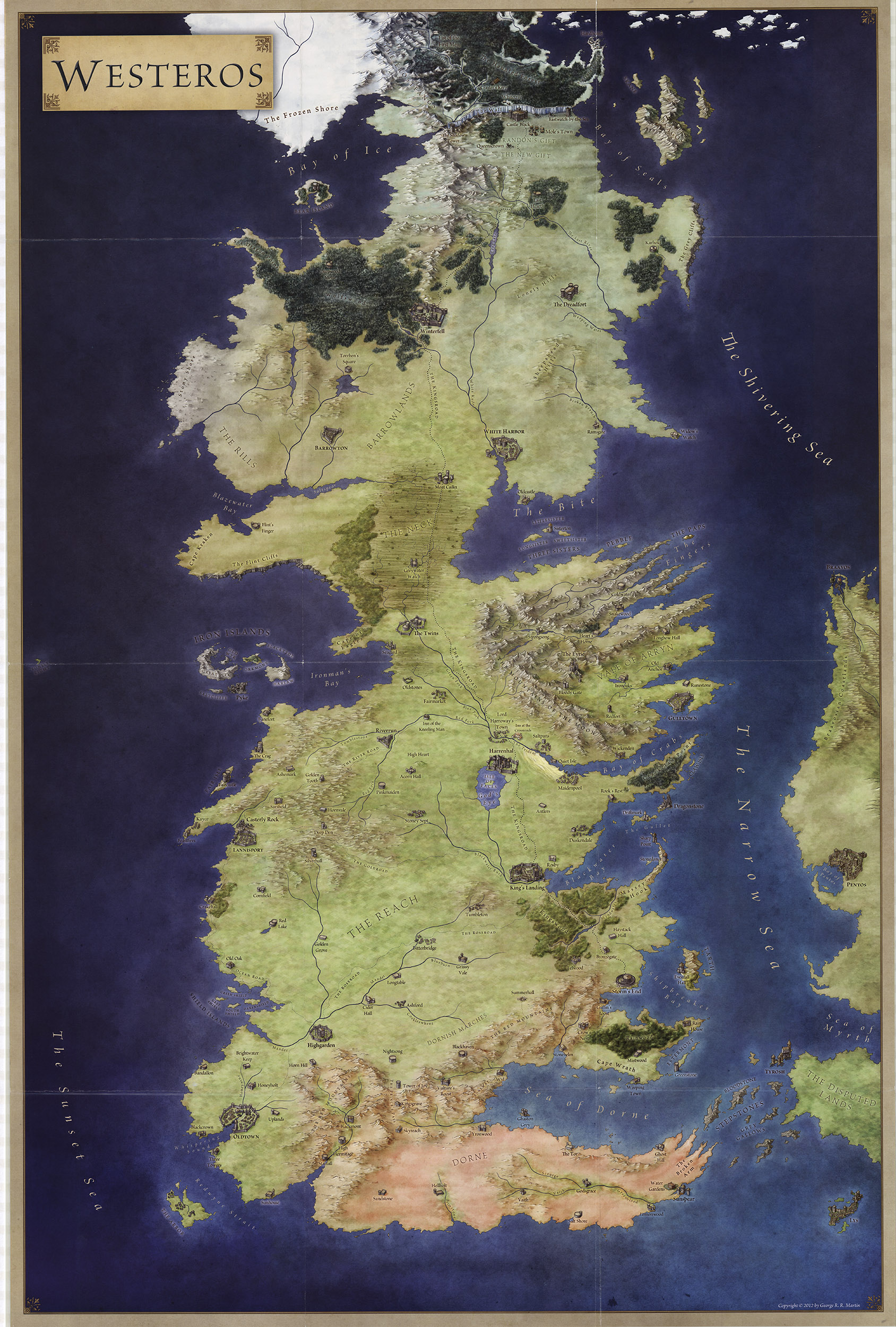

One of 12 maps that were developed to accompany the “Game of Thrones” TV series. Author George R. R. Martin was deeply involved in the creation of these maps, and all were adapted from his hand-drawn versions.

Courtesy of Harvard Library

Harvard University

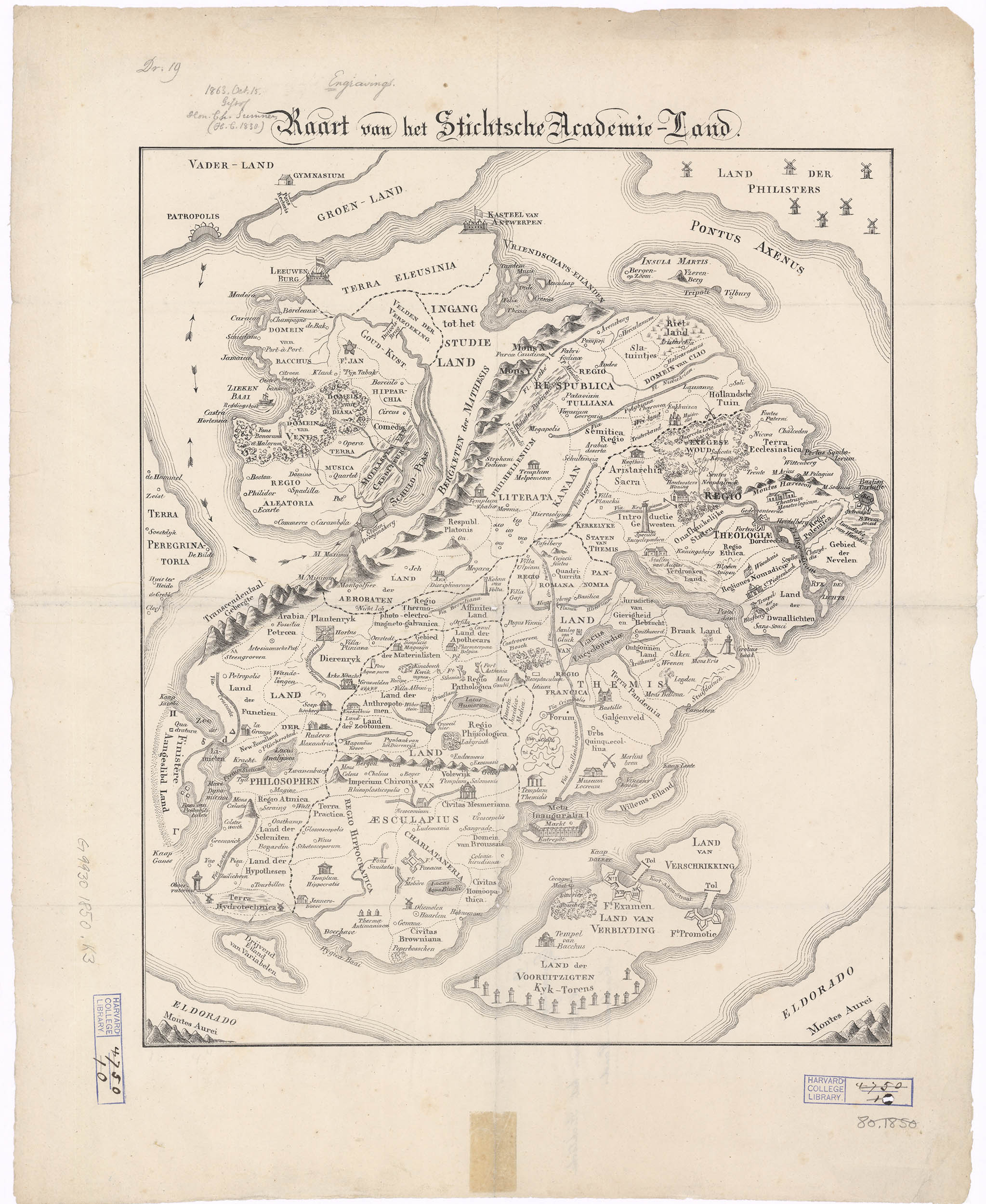

The first map pictured here, from 1834, depicts a journey through the land of academia. One must avoid the Creditors Swamp, the Region of Gambling, the Domain of Bacchus and other pitfalls. The second is a map of Hyrule from the Nintendo game “The Legend of Zelda.”

Courtesy of Harvard Library; Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer