The Carpenter Center was a daring addition to an otherwise traditional campus when completed circa 1963.

Courtesy of Harvard Fine Arts Library

At 60, Carpenter Center takes a rare look back

Four shows inspired by building’s iconic architecture return for anniversary

No one would accuse the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts — celebrating its 60th anniversary this month — of being a neutral gallery space. The boldly constructed modernist building, famously the only structure in North America designed by Swiss-French modernist architect Le Corbusier, is a “silent partner” in each art exhibition that is staged there, according to Dan Byers, the center’s John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Director, and poses a unique challenge to curators who must work with the architecture of the gallery spaces.

Byers laughed, recalling how one visiting artist asked if the columns — an integral part of the building’s structural support — could be removed for a show.

“The architecture being so emphatically present allows one to better understand that gallery architecture is never a neutral space,” Byers said. “Even with galleries that are purpose-built to be flexible or to ‘disappear,’ there are very strong social and ideological design decisions being made — both negative and positive — to create a space that keeps the outside world at bay, making one’s art experience separate from the conditions of daily life.”

“In contemporary art, which is so focused on the present and the future, we rarely get to look back and reconsider our recent history.”

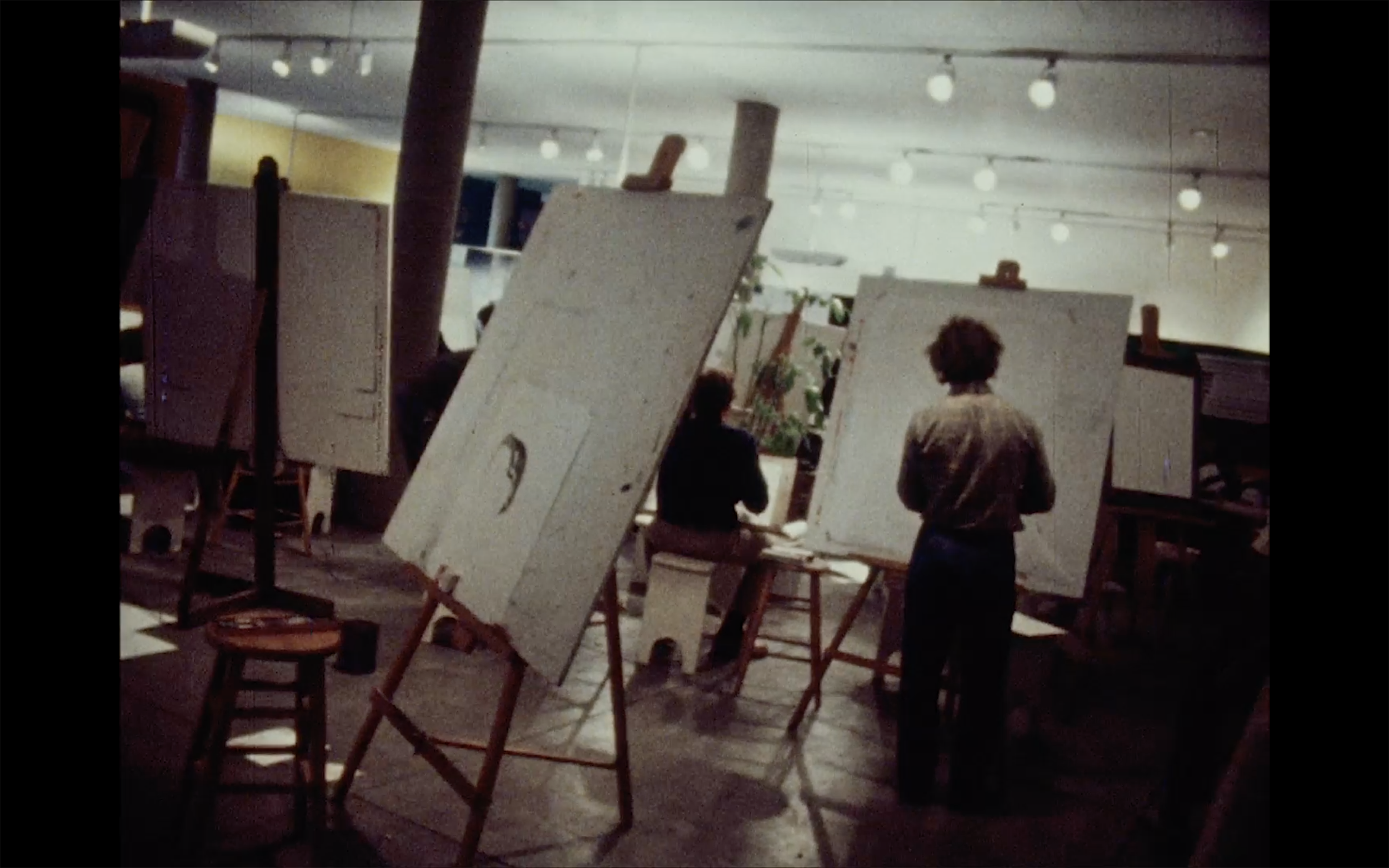

Students work in the building shortly after it opened.

Courtesy of Frances L. Loeb Library

Art-lovers gathered this month to mark the anniversary of the center and the launch of an exhibition that re-stages four of the most iconic works ever presented in the building.

“In contemporary art, which is so focused on the present and the future, we rarely get to look back and reconsider our recent history, which everyday feels less recent and more historical,” said Byers. “This exhibition offers that opportunity.”

Today, the Carpenter Center is home to the Department of Arts, Film, and Visual Studies, and the Harvard Film Archive. It also features gallery space for artists.

“We’re the place that is focused on the art of our time, grappling with our conditions in the present tense, that really privileges the opportunity for artists to experiment and to work through ideas in public that are not fully formed, and are perhaps not ready to be historicized in a museum collection context,” Byers said.

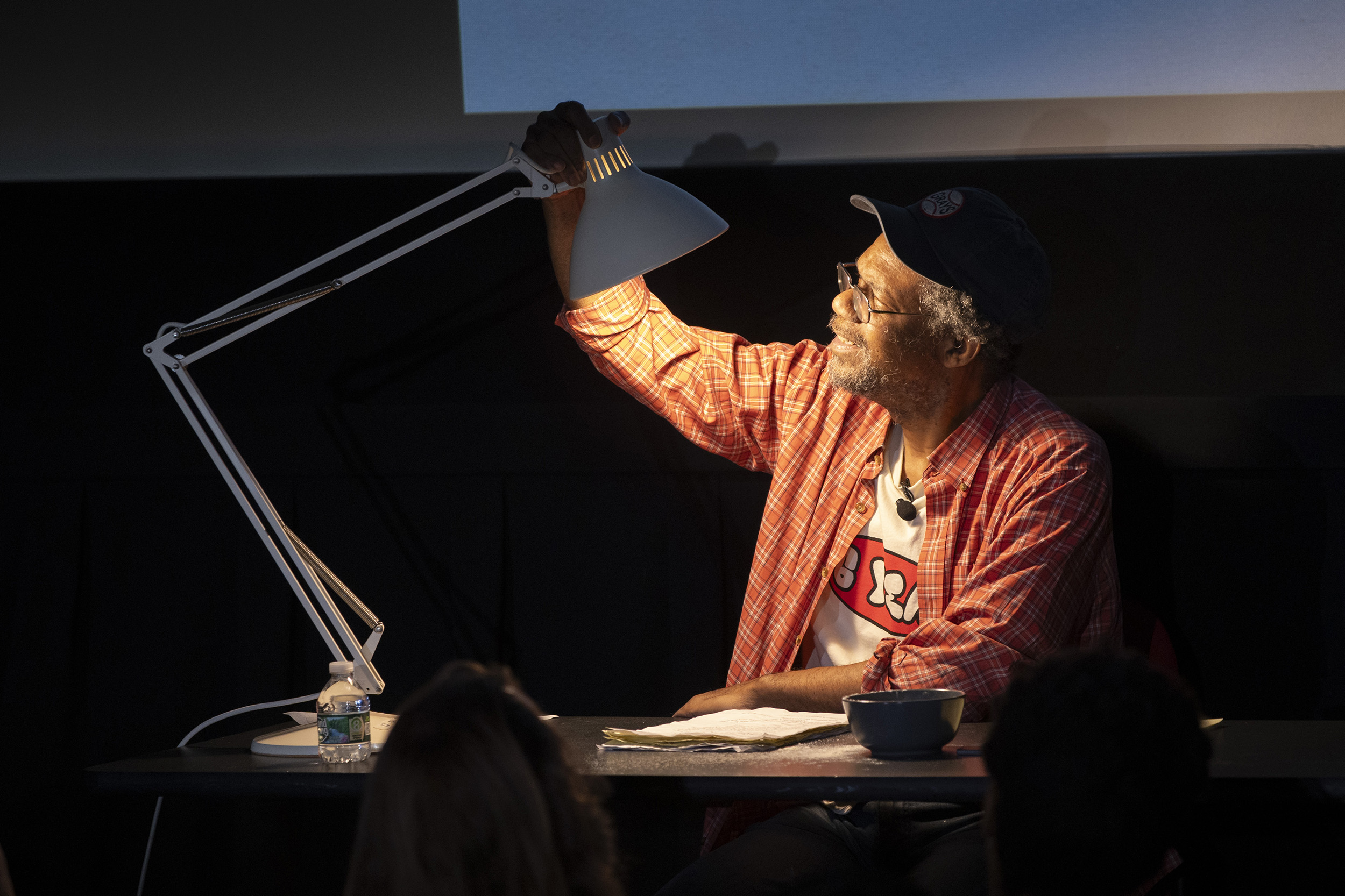

Pope.L discusses his 2009 work “Corbu Pops” at the opening for “This Machine Creates Opacities.”

Photos by Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

The center was built in the 1960s at the recommendation of a committee appointed by former President Nathan Pusey to investigate the place of the visual arts in Harvard’s undergraduate curriculum. Their 1956 report described the tensions, complications, and opportunities of a visual arts education at a large research university and suggested building a center to consolidate artistic entities under one roof.

Le Corbusier was a pioneer of modernist architecture and was instrumental in the creation of the International Style. The building was a controversial addition to an otherwise traditional campus when completed circa 1963, but Le Corbusier believed that a building devoted to the visual arts should be designed with freedom and creativity. The five-level building, supported by concrete columns, features an ascending ramp at its center, with an open design that encourages public circulation and allows viewers to watch art being made.

Dan Byers, center director.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Matt Saunders, professor of Art, Film, and Visual Studies, was an undergraduate student in the 1990s in what at the time was called the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies. He has fond memories of attending artist lectures in the center’s basement, gathering with other students for smoke breaks on the ramp, and crashing on couches in the studio areas after staying too late working on a project.

“For me as a student showing up from public school in Baltimore with a lot of curiosity about art but not a lot of experience, it was just this magical space that felt so different from everything on campus,” Saunders said. “The building itself is a machine for generating relationships and thinking about space and sculpture and lighting.”

Still from “Reality’s Invisible,” a 1971 experimental film capturing academic life in the center.

Courtesy of the Robert E. Fulton III Film Collection and Archive

Now, as a professor, Saunders said the center’s open floor plan encourages a shared sense of community in the teaching space. The core idea of the building, inspired by Bauhaus workshop style, is that classrooms are open and faculty are out on the floor working with the students.

Each piece in the commemorative “This Machine Creates Opacities” exhibition nods to the building. From now through December, visitors can see the 1971 film “Reality’s Invisible” by former faculty member Robert E. Fulton III ’61, featuring Harvard students and faculty, and MIT Professor Renée Green’s 2018 film “Americas: Veritas,” entwining footage of the Carpenter Center and Casa Curutchet, a Le Corbusier building in Argentina. Also on display is the “Corbu Pops” installation by Pope.L, originally staged in 2009 and marked by its baby masks that resemble Le Corbusier himself, as well as the 2004 Pierre Huyghe film “This Is Not a Time for Dreaming,” with puppets enacting the center’s origin story.

Moving forward, Byers hopes the center will house even more initiatives that “teach by doing,” for example staging exhibitions for longer periods of time so students can study them, or adding a space on the first floor where students can try their hand at curating in different mediums.

“The center is still one of the most radical interventions on campus, and even though it’s 60 years old, feels very forward-looking in terms of thinking about community and proposing a vision for art education.”