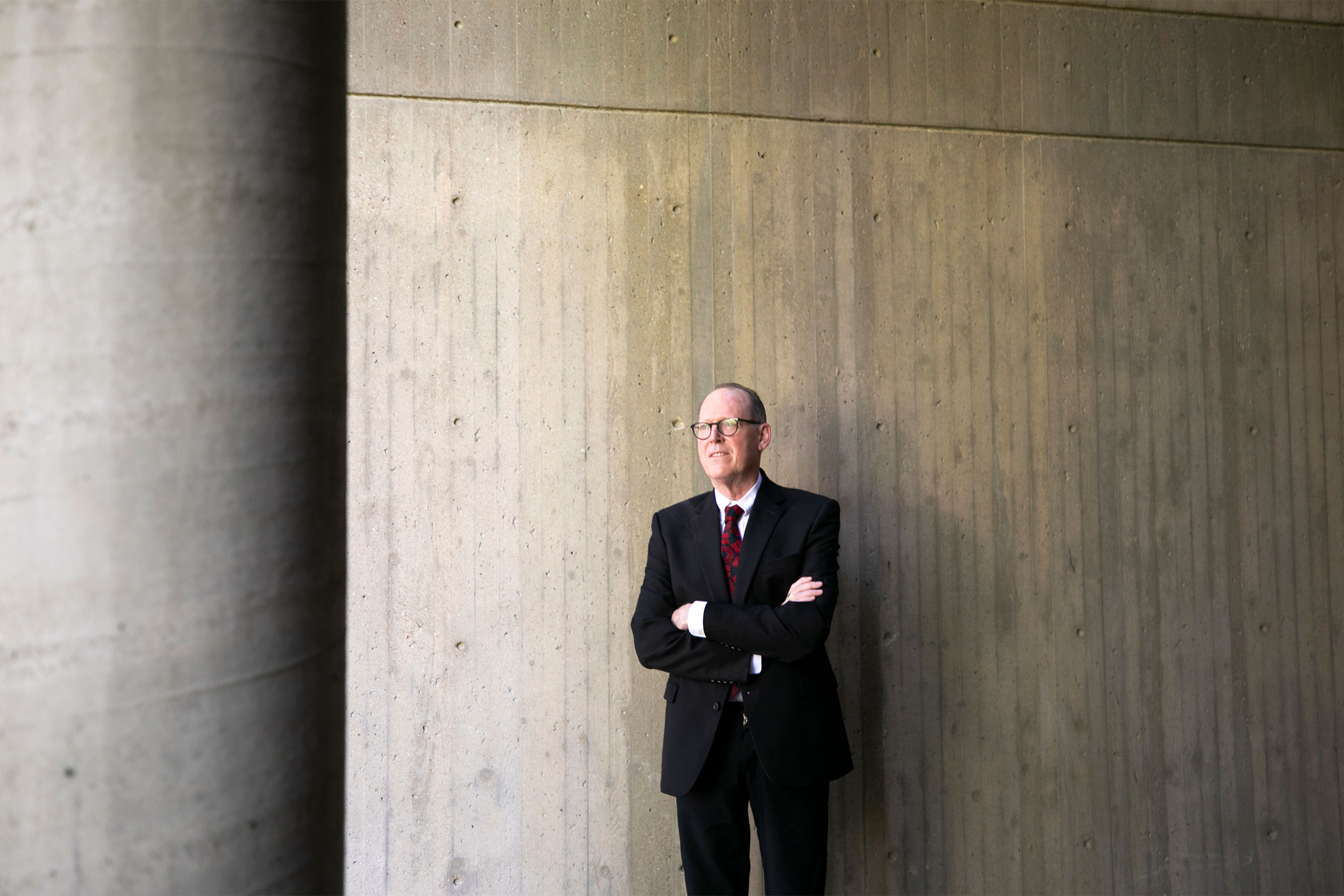

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘When you’re with a patient … their suffering counts more than your suffering’

Symposium honoring late global health pioneer Paul Farmer reflects on achievements, purpose, influence of Haiti

Grief fades, and what remained on Monday in a Harvard Medical School conference room was clarity of purpose: to provide healthcare to the world’s poor, to expand capacity so those in even the most impoverished places can care for themselves, and to teach the next generation so the work continues.

Friends, family, and colleagues of Paul Farmer, the Harvard Med professor and co-founder of the nonprofit Partners In Health, gathered to reflect on his legacy and the global influence of his efforts, which began decades ago in Haiti. That island nation changed Farmer’s life when he visited in the early 1980s. The physician and activist died suddenly last year on the grounds of a hospital and university he helped found in Rwanda.

Speakers at the three-hour symposium, “The Uses of Haiti: Paul Farmer and the Origins of the Global Health Equity Movement,” agreed that Farmer’s firsthand experience with Haiti’s poor after graduating from Duke University transformed him. But the reverse was also true: Without Farmer, Haiti likely would not have become a global example of what is possible, both there and — with the help of some of its professionals — in other countries.

Loune Viaud shown with Paul Farmer.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Joia Mukherjee, associate professor of global health and social medicine at the Medical School and chief medical officer of Partners In Health, recounted an episode from early in her career. She surveyed children in 92 schools about the causes of AIDS while providing education on the disease in Uganda. “Poverty” was the overwhelming response. She brought those results back to the medical and public health establishment, which dismissed them in favor of more biological and behavioral explanations. Since then, the work of Farmer and colleagues has clearly illustrated the impact of poverty on health.

She also noted that one of the most important lessons that Farmer — an avid gardener — imparted is to walk with patients, listen to patients, and believe what they tell you.

“As I and many of us are waking up from this terrible grief, we find ourselves in Paul’s garden right here, because it was the seeds that he planted — that’s all of us — from Haiti to Rwanda, from Rwanda to New York City and back all the way around to Haiti again, building resilient health systems,” said Mukherjee, who is also associate professor of the Division of Global Health Equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “We are those human seeds, and we are here to plant the seeds for the next generation to come.”

The event, in the Medical School’s Joseph B. Martin Conference Center, featured panel discussions on Haiti’s impact on Farmer and on the world. It also featured opening remarks from Harvard President Claudine Gay, whose parents immigrated to the U.S. from Haiti in the 1960s.

Gay said she grew up in a household where Haiti was always present, even if it tended to be invisible to the world outside. She admired the work of Farmer and Partners In Health, she said, describing him as a “why-not thinker, par excellence,” a trait that let him see possibility instead of roadblocks. She believes that outlook should be encouraged at Harvard.

“Why not deliver healthcare to those who need it most? Why not consider all health — physical, mental, emotional, social — when treating patients? Why not combat injustice wherever it exists?” Gay said. “For me, these are some of the ambitious questions that our University must answer if we hope to fulfill our promise. … The courage to listen, to collaborate, and to grow, is the kind of courage that changes the future.”

The event also included a keynote address by Michèle Pierre-Louis, Haiti’s prime minister from 2008 to 2009, who described meeting Farmer in 1995 when he delivered a speech at a conference on democratic transitions during the term of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. She recalled how Farmer’s remarks that day sought to zero in not just on individual ailments, but on the underlying conditions that lead to suffering.

A young Paul Farmer in Haiti.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

“It was the first time I met him and listened to him. He concluded his remarks — after we had a big standing ovation — by saying this: ‘We doctors sometimes have the good fortune to cure patients, to alleviate their sufferings, but our medical knowledge alone does not give us the means to explain where this suffering comes from and how it spreads,’” Pierre-Louis said. “‘Doctors, social workers, psychologists, and anthropologists can prepare and publish their case studies, but they won’t get to the heart of human suffering until they go beyond the level of human experience and place each case in its historical, economic, and political context. Go to the heart of human suffering.’”

“Paul Farmer was an extraordinary individual. We started as his mentors and he became our mentor.”

Arthur Kleinman, Rabb Professor of Anthropology and Farmer’s adviser during his Harvard studies

A year later, a foundation run by Pierre-Louis gave Farmer and the Haitian nonprofit partner of PIH, Zanmi Lasante, the largest grant in the foundation’s history to fund their work to fight AIDS.

“For the rest of his life, in Haiti, in Peru, in Rwanda, in Malawi, in Lesotho, Paul would question the root causes of systemic poverty, taking an interest in people’s lives, collect[ing] data that would enable him to better understand the issues affecting the poor and suffering communities,” he said.

During the panel talks, some of Farmer’s closest associates said he remains a powerful influence on their lives. Some still think of him daily and expressed gratitude for having been able to work beside the man whom Arthur Kleinman, Rabb Professor of Anthropology and professor of psychiatry and Farmer’s adviser during his Harvard studies, described as a “world historical figure.”

“Paul Farmer was an extraordinary individual,” said Kleinman, who is also professor of global health and social medicine. “We started as his mentors and he became our mentor. One of the things that Paul said was that when you’re with a patient, when you’re with someone who needs your assistance, their suffering counts more than your suffering. He had the view that you find yourself as a human being not by going into yourself deeply, but by going out and serving others.”