Solving a mystery of 19th-century literary history

Scholar’s new biography nails down identity of earliest known Black American woman novelist, first theorized by Gates

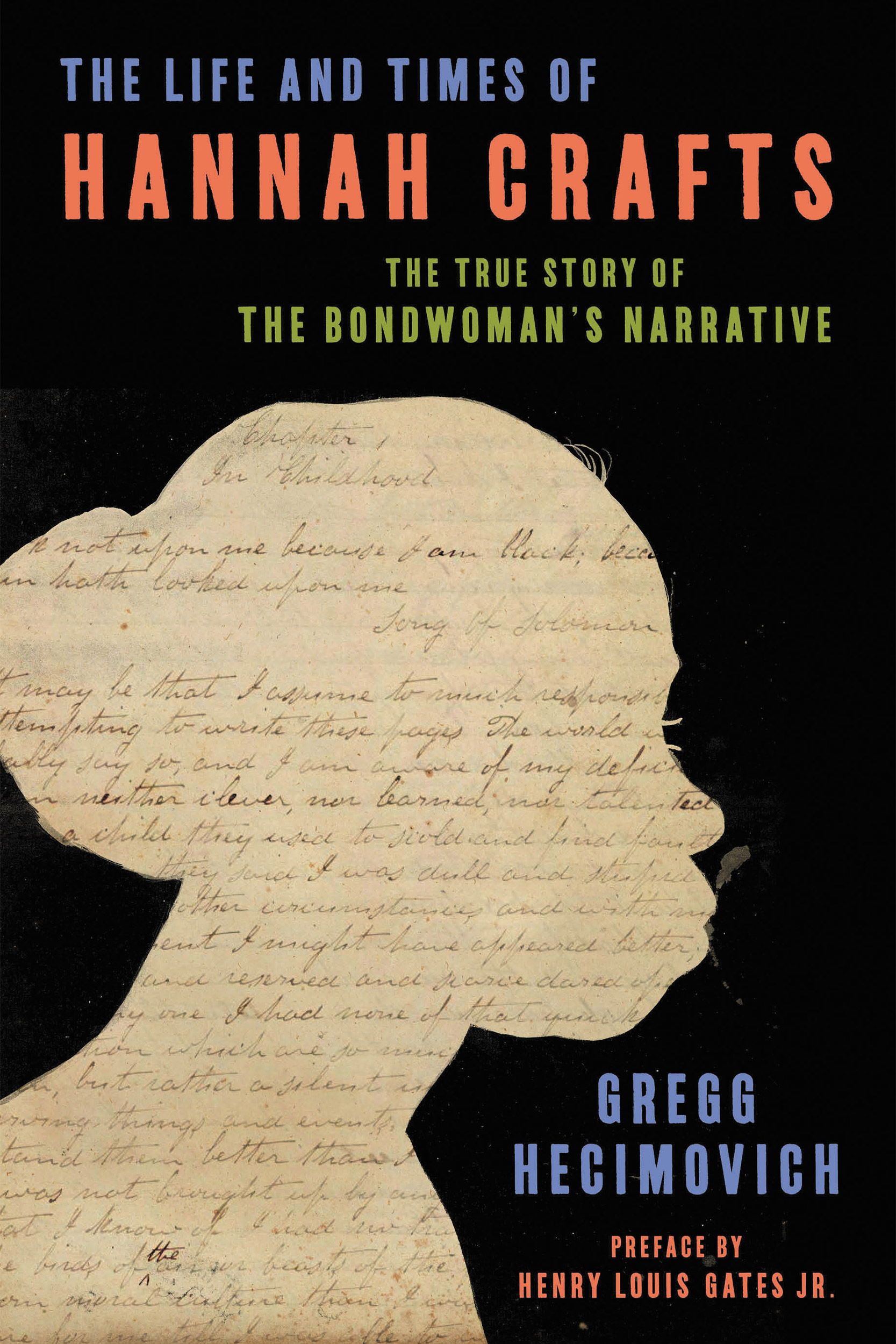

Portraits of Gregg Hecimovich, Hutchins Family Fellow at Harvard University and professor of English at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina. Hecimovich’s book titled “The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts: The True Story of the Bondwoman’s Narrative,” tells the story of the author of “The Bondwoman’s Narrative,” the earliest known novel by an African-American woman. The book has a forward by Skip Gates, who authenticated and published “The Bondwoman’s Narrative” in 2002. Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Gregg Hecimovich first regarded the project with skepticism.

In 2002, Henry Louis Gates Jr., now the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor, published a remarkable 19th-century manuscript titled “The Bondwoman’s Narrative.” Gates, a recognized authority on Black American literature and history, relied on contextual clues and archival work before theorizing the 1850s text to be the earliest known novel by an African American woman — and the first by an enslaved or formerly enslaved female author.

Hecimovich recalled having no qualms about the work’s merits. “Anybody who encountered the novel knew this was an amazing, brilliant piece of literature,” said the professor of English at Furman University in Greenville, S.C., and 2023-24 Hutchins Family Fellow at Harvard.

But the “high level of literacy” seeded doubts about its authorship.

So began a quest to uncover the writer’s real identity. Not only did Hecimovich eventually succeed in pinpointing the best-seller’s formerly enslaved creator, but his work also vindicated Gates’ original judgment.

The specialist in Victorian fiction went on to research and write a fully realized biography. “The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts: The True Story of ‘The Bondwoman’s Narrative,’” published this fall by Ecco, is the culmination of nearly two decades of scholarly detective work including archival deep dives, literary analysis, partnerships with descendants, and even forensic document analysis.

Gates, who is also director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, called the work “the greatest discovery in the history of African American literature” at a campus book talk last week.

Twenty years ago, the Harvard professor was unable to precisely identify the author of “The Bondwoman’s Narrative,” who described herself as a “fugitive slave” and signed her work with the name Hannah Crafts.

But the lightly fictionalized autobiographical text featured among its main characters John Hill and Ellen Sully Wheeler, who were actual North Carolina enslavers. Early on, Gates discovered the couple possessed a vast library, generously stocked with classics and new releases alike, possibly explaining the array of literary allusions in Crafts’ narrative.

Hecimovich was drawn into the mystery in 2003. At the time a professor and associate dean at East Carolina University, near one of the Wheeler’s 19th-century plantations, he was recruited for local archival research by Hollis Robbins, M.P.P. ’90, a scholar of 19th-century American literature now at the University of Utah.

“I thought I was going to discover that the author was one of the white nieces of Mrs. Wheeler,” Hecimovich confessed. Teaching enslaved Black Americans to read and write had been criminalized in the antebellum South. Not only were the Wheeler nieces on record as literary, he reasoned, they were known to have a beef with Ellen Sully Wheeler, who is “mocked in the novel.”

Hecimovich was hardly alone in his suspicions regarding the book’s provenance. In fact, the 2004 collection of essays “In Search of Hannah Crafts,” edited by Gates and Hollis, included one especially doubtful take by the late Thomas C. Parramore, a history professor at Meredith College in Raleigh, N.C. As Hecimovich put it: “He was a very good historian, but of an earlier generation that was just blind to the lives of enslaved people.”

In the end, the regional historian provided Hecimovich with something of a reverse road map. “It really flipped for me as I dug into Parramore’s records,” said Hecimovich, who described making key discoveries while working from the very same source material. “When I could knock down, quickly, every reason he said this couldn’t have been written by an enslaved woman — that helped me find her.”

In 2013, Hecimovich’s discovery of the author’s identity made front-page headlines. “What I was able to discover is that there was one enslaved woman with a high degree of literacy who lived with the Wheelers at the time the novel was written,” summarized Hecimovich, whose findings were corroborated by document experts who traced Crafts’ manuscript paper to reams used in the Wheeler household between 1856 and 1857.

“And that woman’s name, at the time, was Hannah Bond.” (The author later took the last name of Horace Craft, a farmer in upstate New York who aided in her escape.)

Passages from the novel fit Crafts’ life story “like a glove,” Hecimovich added. That goes for the poor white woman in the book who teaches the narrator to read, matching a contemporaneous newspaper account of an area Quaker jailed for educating Black children. Ditto for the author’s accounts of comings and goings from various Wheeler residences in North Carolina and Washington, D.C.

At the same time, the author conjured happier outcomes for other life events. For instance, the book imagines a blissful reunion with the mother who was sold away before Crafts’ 10th birthday.

Similar treatment is given to sexual predation, a theme Hecimovich characterizes as “extremely pervasive” in the storytelling. He concludes that the author, who describes herself as “almost white,” was the product of an enslaver’s assault on her mother. Crafts was likely forced into a similar arrangement, with the biographer implicating another white man from the same extended family of slaveholders as her father. “But when she tells that story in the book,” Hecimovich observed, “she does it in a way that her autobiographical protagonist is never harmed.”

Over the years, literary scholars have noted Crafts’ interplay with works by Charles Dickens, Frederick Douglass, the Brontë sisters, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Hecimovich found further evidence that Crafts was forced to attend a minstrel show that parodied Stowe’s 1852 hit “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

It turns out, the author was living in freedom when this spectacle was repurposed for the novel’s pivotal chapter — featuring a “genius” blackface scene that exacts literary revenge upon the Wheelers. “They are the fools, the greedy characters, the comic figures who have no idea,” Hecimovich said. “Her novel completely flips the script.”