Zheng-Yi Chen of Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and Harvard Medical School co-led the team that developed the gene therapy.

Gene-therapy breakthrough allows congenitally deaf children to hear

Harvard scientist co-leads research, which targeted specific condition, may yield other treatments for more of the 30 million kids with genetic hearing loss

A novel gene therapy approach has given five children who were born deaf the ability to hear. The method, which overcomes a roadblock presented by large genes, may be useful in other treatments, according to researchers.

The work, conducted in Fudan, China, by a team co-led by Zheng-Yi Chen at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and Harvard Medical School and by collaborators at Fudan University’s Eye & ENT Hospital, treated six children aged 1 to 7 who were suffering from an inherited mutation of the OTOF gene, which manufactures a protein important in transmitting signals from the ear to the brain.

Five of the six children showed improvement in hearing over the 26-week trial, with four outcomes described by researchers as “robust.” With hearing a critical factor in language acquisition, researchers also measured speech perception — the ability to recognize sound as speech — and all five of those who responded to treatment showed improvement there.

The three older children, with cochlear implants turned off, could understand and respond to speech by 26 weeks, with two able to recognize speech in a noisy room and have a telephone conversation.

“This really opens the door to developing other treatments for different kinds of genetic deafness,” said Chen, a researcher at Mass Eye and Ear’s Eaton-Peabody Laboratories and a professor of otolaryngology, head and neck surgery at Harvard Medical School. Chen added that the study provides proof-of-concept that prior work in laboratory animals does translate to humans. “Now we can move forward in humans quickly. This has given us a real boost of confidence.”

Hearing loss affects more than 1.5 billion people worldwide, Chen said, including about 30 million cases of genetic impairment in children. Those in the current trial suffered a condition called DFNB9, resulting in total deafness due to a mutation in the OTOF gene.

The gene encodes the otoferlin protein, produced by cells in a snail-shaped part of the inner ear called the cochlea. In the cochlea, sound waves are translated into electric pulses carried by nerve cells to the brain, where they are interpreted as sound. Otoferlin plays a role in transmitting pulses from cochlear cells to the nerves and without it, sound is translated into electric signals but never reach the brain.

Chen, senior author of a paper on the work published this week in the journal The Lancet, and Yilai Shu, another senior author and deputy director of the Fudan hospital where the work took place, said DFNB9 provided an attractive gene-therapy target because it is a relatively simple condition, caused by a single mutation and involving no physical damage to the cochlear cells.

Shu, a postdoc in Chen’s lab from 2010 to 2014, said the large response to the request for study participants reflects the need for improved treatment for congenital deafness for which, Chen pointed out, there are no approved drugs. Researchers ultimately screened 425 potential participants, enrolling just six.

Of the six, four had cochlear implants — which, with training, allow interpretation of speech and sound — in one ear while the two youngest participants, ages 1 and 2, had no implants. When the implants were switched off, all participants were completely deaf.

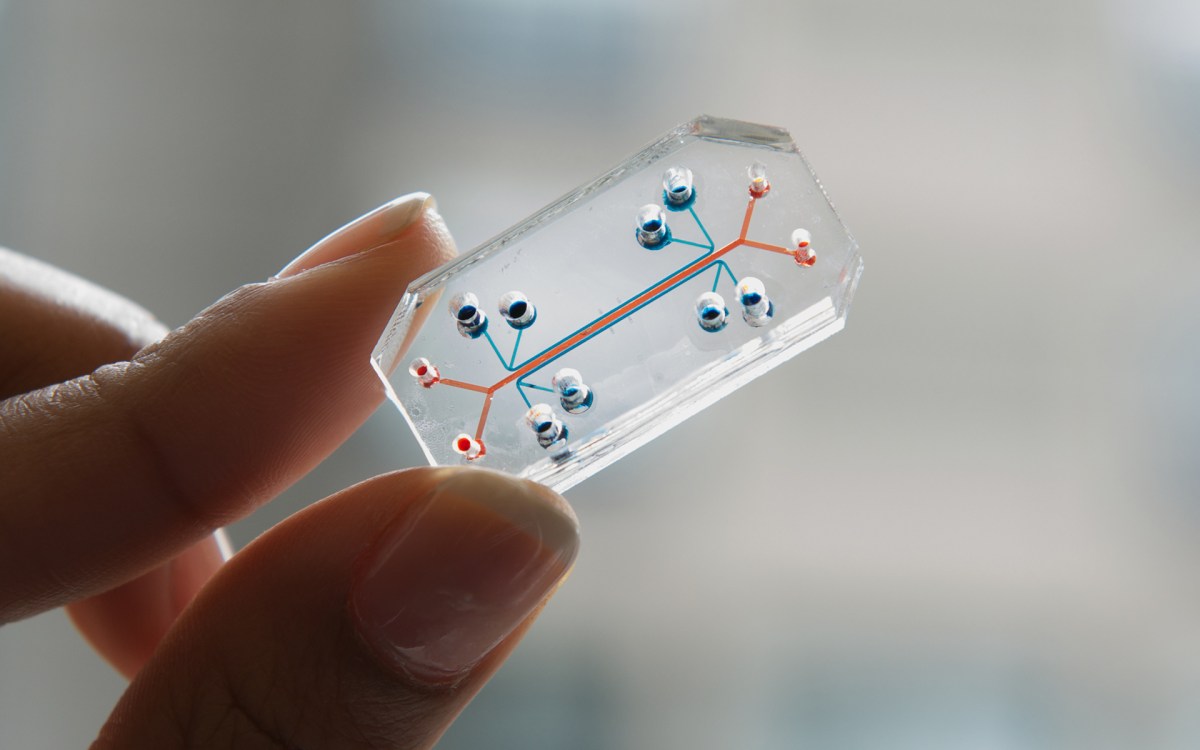

Before the trial began, researchers had to tackle a significant technical problem related to the size of the OTOF gene. The procedure called for the gene to be inserted into the cochlea using a type of virus researchers commonly use for this purpose.

The virus inserts the gene into the DNA of target cells, which then begin to manufacture the missing protein. The problem in this case is that the OTOF gene is too big for the virus to hold. Researchers got past this by dividing the gene into two, encapsulating the halves into separate viruses, and then injecting a mixture with both halves of the gene into the cochlea.

Though the viruses inserted the gene halves at different spots on the cells’ DNA, when those halves were expressed, cellular machinery assembled the complete protein, restoring the cells’ ability to transmit signals to the brain.

The mixture was injected into the fluid of the inner ear, and the viruses made their way to the target cells as they would if they were a naturally occurring infection. Researchers had to wait for four to six weeks after injection to see the first signs that hearing was being restored.

In five of the six participants, the improvement was progressive. The three older children, with cochlear implants turned off, could understand and respond to speech by 26 weeks, with two able to recognize speech in a noisy room and have a telephone conversation.

The younger participants showed improvement in the ability to recognize speech but were too young for some tests. Anecdotally, Chen said the 1-year-old has been able to respond to stimuli and begun to verbalize simple first words, like “mama.” One of the six participants showed no improvement, which Chen and Shu said is poorly understood but may have been due to an immune reaction to the viral vector.

In some cases, Shu said, parents noticed the response even before the researchers conducted their first tests at four weeks.

“We first found out when the parents told us: When her mother called her, she turned back,” Shu said. “All of them are very hopeful. They were very, very excited, and all of them cried when they first found that their child can hear.”

The project, done in December 2022, was the first to make use of gene therapy to treat this condition, but several studies in various stages are targeting the same condition. Chen said that will hopefully accelerate work that, though it has taken years to reach this point, has recently seen rapid progress.

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Key R&D Program of China, Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality, and Shanghai Refreshgene Therapeutics.

Next steps, he and Shu said, include monitoring the participants in this study, as well as beginning a new study with participants from more diverse backgrounds. If all goes well, Chen said, approval of the treatment by U.S. federal regulators could be three to five years away.

“This is truly remarkable. When we tell the story, even for our colleagues, it brings a tear to the eye,” Chen said. “I’ve been working in this field for three decades, and I know how difficult it has been to come to this point. I also know we’re at the juncture of a great future.”