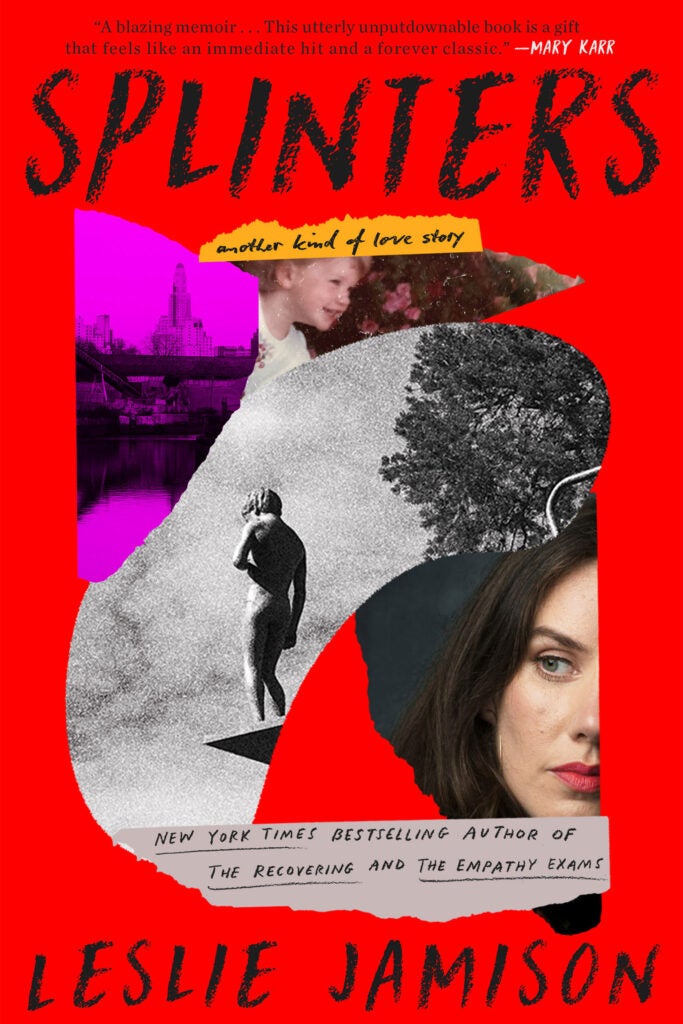

Photo by Grace Ann Leadbeater

Can you embrace deep joy amid deep loss?

Leslie Jamison traces how first-time motherhood, crumbling of marriage left her with new, different life

Leslie Jamison’s work has been compared to that of Joan Didion and Susan Sontag and, like those writers, she is no stranger to grinding loss, deep thinking, and luminous prose. In her latest book, “Splinters: Another Kind of Love Story,” the essayist and memoirist writes about the birth of her daughter, the end of her marriage, and the question: Is it possible to embrace joy amid heartbreak?

Jamison ’04, who has an M.F.A. from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a Ph.D. from Yale, is an associate professor of writing at Columbia and will be coming to The Brattle Theater to talk about “Splinters” on Feb. 21. She will be joined in conversation by novelist Claire Messud, the Joseph Y. Bae and Janice Lee Senior Lecturer on Fiction. She recently spoke with the Gazette about her writing. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Was there a specific inspiration for writing this book?

I wanted to write about simultaneity. I felt humbled and awestruck by the way this particular area of my life had held such intense joy and such intense sorrow at the same time. It was almost impossible to disentangle them. I wanted to use the experiences I had gone through — marriage, divorce, early motherhood — to write an account that could resonate with anyone, no matter what experiences they shared.

You often take on very tough, personal topics in your writing — “The Recovering” (2018), for instance, deals with your own battle with sobriety. Did “Splinters” feel different than your previous books?

Yes and no. I think all of my writing has been obsessed with thresholds of transformation. My essay collection, “The Empathy Exams,” is really interested in pain as a site of transformation: How are we transformed by our own experiences of pain? How are we transformed by encounters with other people’s pain?

My book “The Recovering” is really interested in sobriety and recovery as thresholds of transformations: How does a person’s relationship to the world change when she pivots from addiction to recovery?

And then “Splinters” is really interested in reckoning with two different thresholds of transformation: divorce and motherhood.

But I think what feels different about this book is both the nature of what I’m writing about and the form it took. I was writing about motherhood for the first time, as well as my own life having left its script behind it, at least the script that I had imagined for it.

I’ve mainly worked in the form of hybrid essay, pieces of writing that weave together personal narrative, cultural criticism, history, literary journalism, and literary criticism. With this book, I stayed in a very distilled, visceral, proximate account of one particular experience.

Tell us more about the title of the book, “Splinters: Another Kind of Love Story.”

It refers both to the emotional content of the book and the way it’s written. It’s a reckoning with certain experiences that get under the skin and stay there, often in a painful way that feels like they become part of you. And the book is also built of these, short, whittled shards of prose that that bring you very powerfully into a moment of experience and then take you out of it.

My hope for it was that it would be a book that you would sit down with and not put it down until you were done. I know that’s not always going to happen, but a lot of people have described having that “stayed up until 3 in the morning” feeling with it.

You used the word “visceral.” There’s a moment in the book when your daughter is only a couple of weeks old, and she won’t stop crying. You wrote: “The harder I banged my head against the wall, the steadier I tried to keep her — cradled by a pair of loving arms attached to a woman losing her mind.” It’s a very honest portrayal of motherhood not often seen.

Sometimes it’s hard to see representations of difficulty or complexity because they resonate. They hold a mirror to certain parts of experience that are uncomfortable or hard to think about.

But I think that beneath that discomfort, there’s a great consolation in seeing experiences that are telling the truth about what’s difficult and what’s complex, especially when it comes to motherhood. There’s nothing more lonely-making than accounts of motherhood that don’t make room for what feels difficult about it.

“There is no artistic god that I worship more fully than the god of specificity. I always want to write the visceral details, the actual breakfast food on the table, the actual thing somebody said.”

There are multiple points in the book where you mention the profoundness of the experience, but also the difficulty of putting it into words. What helped you articulate your experience?

Part of my writing process is note-taking. I’m often taking notes, either in documents on my computer or as a sporadic but long-term diary keeper.

Whenever I have a moment — even an ordinary afternoon with my daughter — that makes an impression on me for some reason, I try to capture it. I’ll just have moments where my “Spidey-sense” is activated in some way. I don’t totally know what to make of them, but they’re interesting. So I jot those down in some way, shape, or form so they won’t be lost.

There is no artistic god that I worship more fully than the god of specificity. I always want to write the visceral details, the actual breakfast food on the table, the actual thing somebody said. When you’re writing fiction, specificity is always available to you in a certain way because you can make things up. But when you’re writing nonfiction, if you want that specificity to be available to you, you have to take good notes.

In your book, you were very careful with certain details of your life, like those surrounding the end of your marriage. But there were other moments that were incredibly open and direct. How did you decide when to go deep and when to pull back?

Whenever I’m writing from personal experience, I’m always thinking about how the experience can help me investigate certain questions.

With “Splinters,” I was always thinking about the moments that could help me illuminate some tension about mothering — for example, the tension between the ways that mothering feels endlessly profound and endlessly boring. What are particular scenes that could help me get that simultaneity across? Or what does it mean to carry a feeling of love and appreciation for a person, even if the life you were trying to build with them didn’t work out?

That helps me decide what’s going to be there and what’s not, as well as how deep I need to go to get to the emotional gemstone that I need.

And then there are lots of parts of my life that I’m just never going to make public for the sake of my own privacy or another person’s privacy.

With this book, there’s so much of the story of what was lived that isn’t on the page. But my hope was to create an experience for a reader that can feel whole and comprehensive, even if there are, of course, many things that I lived that aren’t on the page.

Every writer has critics. How do you take criticism, when the critique is directed at a literary work that’s based on your personal lived experience?

I take it very personally every time! It’s a great question, and the other day I was telling my students about one of the very first nonfiction workshops I was ever in. I wrote an essay where I confessed some of — what I thought of as — the worst thoughts and feelings I ever had.

I remember somebody in that workshop saying, “I wonder if there’s such a thing as too much honesty; because I really dislike the author of this essay.” And then he paused. And he was like, “I mean, sorry, the narrator.” It was such a perfect moment of encapsulating that tension.

There’s plenty of criticism about nonfiction that is clearly directed at the craft. But there’s also so much criticism that feels like a criticism of your life choices or some element of your humanity: your selfishness or solipsism; the way you treated other people; the way you treated yourself.

I fantasize about being a person who has developed such a thick skin that I don’t care about any of it anymore. But I do care what other people think. I think I’ve reached a place where I’ve accepted that I care and I try to make space for it as an investment in the work and the art. Alongside of that, I also believe that you write the work for the people who love it, not the people who don’t.

How do you feel your personal story connects to something beyond yourself?

One way I think about personal narrative is somewhat akin to the concept of a case study. By examining very closely one individual experience, we’re not necessarily understanding that experience as universal or representative of everyone, but there is a faith that by looking closely at an individual life, you can find things that resonate with other lives.

And I have found in all these years of doing this kind of writing that people find their own veins of resonance. The more specific you are with your own experience, the more — rather than less — likely they are to find parts of themselves in there.

Or alternatively, sometimes when you’re reading about an experience of the world that’s very different from your own, there’s a sense of getting information about another way of being alive.

But I also hope that some of the questions at the core of the book can bridge the gap from my life to other lives: How can happiness carry grief tucked inside of it? What does hope look like in the aftermath of rupture? How can you arrive at a sense of beauty that doesn’t depend on that beauty being pure or untarnished?

My hope is the questions themselves will allow the scope of the book to reach its tendrils into all kinds of lives that I couldn’t have imagined.