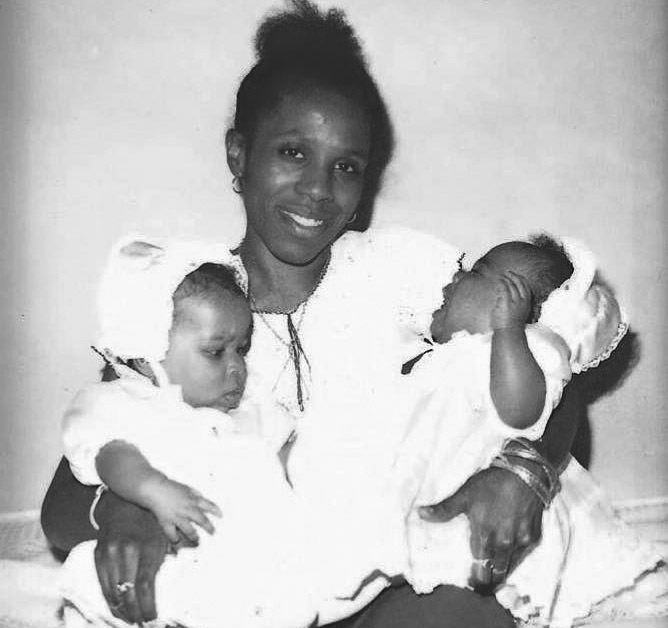

Dale Blackstock with her twin daughters.

Photos courtesy of Uché Blackstock

Was racism a factor in mother’s leukemia?

Dale Blackstock grew up low-income, became a physician. Her death left daughter Uché, also a doctor, with a lesson on color, class, healthcare

Excerpted from “Legacy: A Black Physician Reckons with Racism in Medicine” by Uché Blackstock ’99, M.D. ’05, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Our mother was a remarkably vibrant and athletic woman. She regularly ran 20 miles a week, a habit she had first picked up in medical school to calm her frazzled nerves. After my twin sister, Oni, and I were born, she began squeezing her daily run into the very early mornings before we got up for school and she had to go to work.

In her younger years, she had run marathons, and even once won as the first woman to cross the finish line. And although after having twins, she gave up running very long distances, she’d still regularly compete in 5K and 10K races in Prospect Park and in Manhattan’s Central Park. She had experienced her own share of racism and sexism while running, with white male runners spitting at her and trash-talking to try unsuccessfully to psych her out. Despite these unpleasant experiences, she encouraged Oni and me to join her in her passion, and I ran my first race with her when I was only six years old. It was a family race in Prospect Park. She ran alongside me the whole way, cheering me on. A picture of us running together was even published in one of the local Brooklyn papers.

As Oni and I got older and entered our preteens, we joined the New York Road Runners club and began competing with her. Even when we were teenagers and she was in her forties, our mother always crossed the line before us — she was unstoppable. Then she would wait for us there, cheering us on.

By the time Oni and I left home to go to Harvard University, where my mother went to medical school, to study premed, we just assumed that our mother was invincible.

The first time I remember noticing any change was during a 10K race. It was the summer of 1996, between our freshman and sophomore years. Oni and I had signed up to race with our mother in Central Park. Usually, we would expect her to be ahead of us, but this particular day, I remember looking over my shoulder and thinking, “Where is she?” When she came in a good few minutes after we crossed the finish line, I asked her if she was okay.

“I don’t know what happened,” she replied between deep breaths. She was bent over with her hands on her hips and head down. “I just feel really tired.”

On the way home, our mother confided to Oni and me that she had been feeling under the weather for a while. She had been to her physician; they had done blood work and believed she had a vitamin B12 deficiency because her red blood cells were so big. When you don’t have enough vitamin B12, your bone marrow makes abnormally large red blood cells. She was getting B12 shots, but they didn’t seem to be helping. Eventually, her doctors did a more thorough workup, including a bone marrow biopsy. This took several weeks. I remember telling her to please keep us posted about the results, and soon after that we returned for our second year at Harvard.

One day, when we were back in Boston and two months into our sophomore year, we got a call from our mother’s sister, Auntie Joanie. She lived in the Boston area and had always been like a second mother to us. We would see her often, so it wasn’t unusual for her to call and come over to visit. When I saw our aunt’s face as she walked into our dormitory that day, I knew it was bad news — her usual cheery disposition was gone, and instead she looked distraught, her eyes somehow sunken into her features. We walked out to the courtyard outside our dorm, which overlooked the Charles River. It was a slightly chill fall day, the clouds overhead casting dark shadows across the silvery water. As she told us about our mother’s diagnosis, all three of us started to cry. I realized that our mother must have sent her sister to tell us because she couldn’t bear to do it herself. I remember dropping to my knees on the ground and sobbing.

Our mother had been diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), a type of blood cancer. Her doctors gave her two to three months to live. The chemotherapy treatments started right away. Oni and I spent that year traveling back and forth between Boston and New York, on buses, trains, and airplanes, while our mother was in and out of the hospital.

Despite the odds, she told us that she would beat the disease, that she would endure the harsh chemotherapy side effects, infections, and sheer pain and discomfort to do so. That she was a fighter.

There are multiple risk factors for AML, and although the official list doesn’t include racism, I can’t help but wonder about the many ways systemic racism may have contributed to my mother’s increased susceptibility to the disease. Not long after her diagnosis, she came up to Boston for a second opinion at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, one of the leading cancer centers in the country, if not the world. After her visit with the oncologist, she told us that the doctor who had looked at her karyotype — a picture of the chromosomes at the cellular level — said it seemed to him as if she had been exposed to high doses of radiation at some point in her life, which would have increased her risk for her type of cancer.

At the time, I didn’t think to ask how this might have been possible. I was too distraught and worried about her to think much about anything else. Since that time, I’ve come to understand that my mother may well have been exposed to radiation as a child or perhaps even in utero. Today, there are four designated “Superfund” sites in New York City, locations that the Environmental Protection Agency has marked as polluted by hazardous waste and in need of cleanup. Two of the four sites are radioactive dumping grounds: one of these is in Brooklyn and one is on the Brooklyn-Queens border, both in Black and Latinx communities where my mother lived. Multiple studies show that people who reside in predominantly low-income communities of the kind my mother grew up in have much higher exposure to toxic environmental contaminants in general, which in turn can lead to higher instances of cancer.

We also know that these high rates are compounded by the fact that Black patients often have delayed cancer diagnoses due to lack of access to health care and lack of quality, culturally responsive care. By the time my mother’s leukemia was caught, it was already extremely advanced and therefore much more difficult to treat. When her oncologists looked back at her blood work, they could see that her red blood cells had been enlarged for a while, at least one to two years. But this key indicator for her disease wasn’t picked up by her primary care physician in Brooklyn, who had told her at first, when her symptoms began, that she needed to take vitamin B12 for a deficiency.

Aging is another key risk factor in my mother’s disease. Although people can develop AML at all ages, the risk increases substantially as someone gets older. My mother was in the prime of her life, in her midforties, when she was struck down by AML. But what if the cells in her relatively young body had gone through an accelerated aging process due to her life experiences as a Black woman? Studies have shown that the higher levels of stress to which Black people are subjected on a day-to-day basis due to racism can, in turn, cause our cells to divide and deteriorate, accelerating the body’s aging process. This phenomenon has been dubbed “weathering” or “premature aging” by public health researcher Dr. Arline Geronimus, who first noted the effects of increased stress on the health of pregnant teenagers in Black and Latinx communities in New Jersey when compared with their white counterparts.

Like anyone Black in the United States, our mother had experienced the excruciating pain of that stress. Growing up in poverty, she had been forced to constantly move to different schools and apartments due to housing insecurity, and she never knew if there would be enough food on the table. She was the first person in her family to go to college, the first to have a professional career, navigating a demanding medical career without mentorship or support. On top of this, there was the everyday discrimination she experienced as a matter of course. I can remember the time Oni and I watched in horror as a CVS pharmacy security guard accused our mother of stealing something from the store and demanded she open her bag. Our always firm and confident mother was suddenly flustered, embarrassed, made vulnerable by this awful stranger who somehow held power over her, and by extension us. We were furious and scared, clinging to her as she opened her purse.

People often talk about “going to war” with cancer or “the fight” to combat the disease, but we hear less about how the “war” and “fight” a person endures before they get visibly sick may have contributed to a physical diminishment of the body. And our mother is far from an outlier. Today, the National Cancer Institute’s database shows that Black patients with AML have a 12 percent increased risk for mortality compared with white patients who have the disease, but we will need far more studies that include Black people before we truly understand why. To this day, I wonder whether our mother might have lived longer had she not been Black in America. Although we’ll never know for certain, what we do know is that the ongoing impact of racism on Black bodies continues to leave untold loss in its wake.

Copyright © 2024 by Uché Blackstock, M.D.