‘Curiosity as a tool of change’

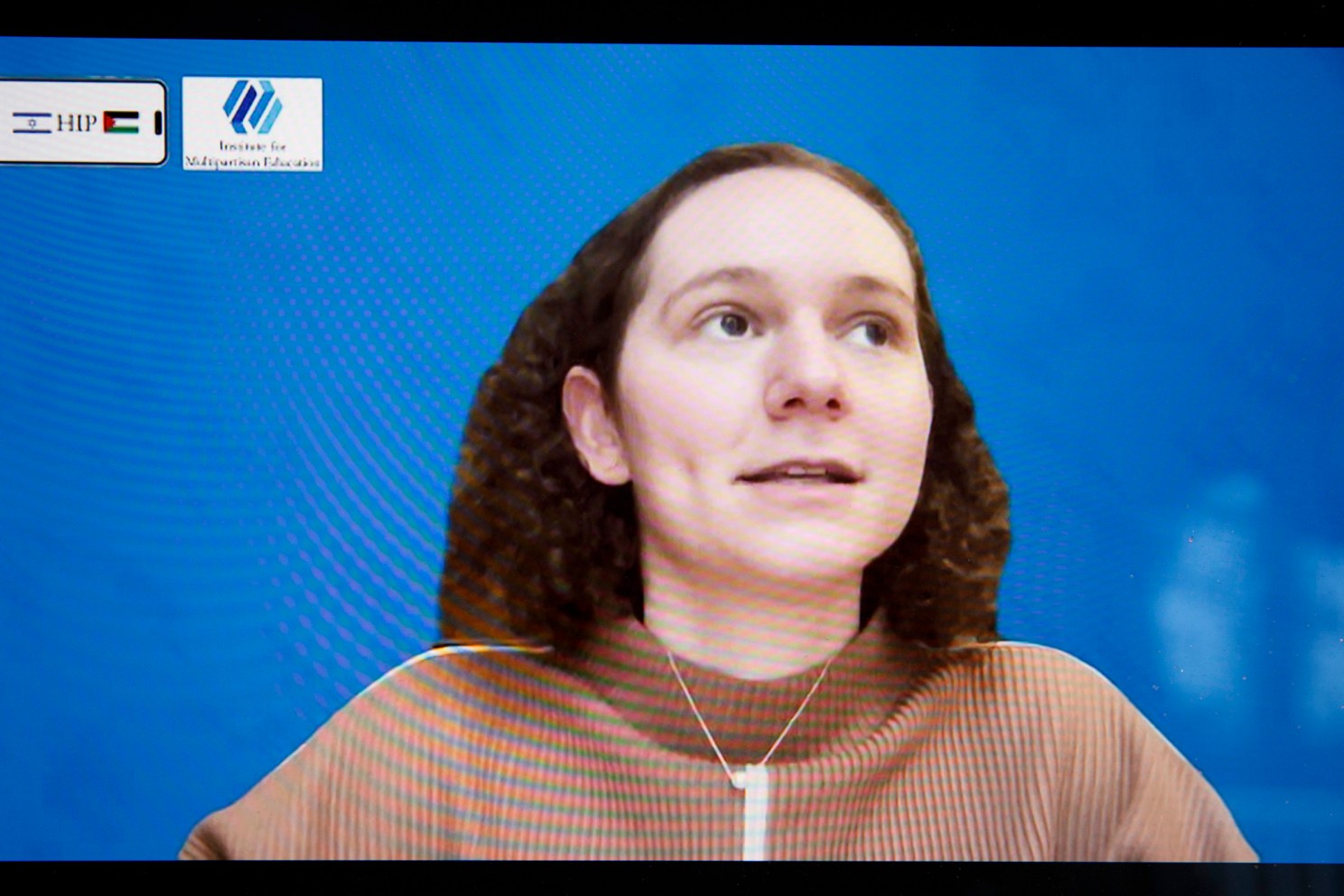

During a virtual talk, Shira Hoffer ’25 explained the inspiration behind her Hotline for Israel/Palestine project. “The first question I received was, ‘What’s the best solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?’ Which I still haven’t answered.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

College junior creates text hotline to provide nonpartisan information, resources on Israel-Hamas conflict

Just 10 days after the start of the Israel-Hamas war, Shira Hoffer realized people had a lot of questions about all kinds of issues surrounding the attack, the history, politics, and geography of both sides, as well as who stood where on what in the nation and the world.

That insight led the junior studying social studies and religion to create the Hotline for Israel/Palestine, which allows anyone, anywhere in the world, to pose questions in a judgment-free setting via text. The questions include issues like “Should there be a cease-fire between Israel and Gaza?”

So far, hundreds of queries have been answered by the nearly 30 carefully screened volunteers who walk an ideological tightrope to supply nonpartisan information that is factually accurate and verifiable, along with resources for responsible, informed takes that reflect where both sides stand.

Hoffer spoke to a crowd virtually on Monday as part of the Edmond & Lily Safra Center for Ethics speaker series on the inspiration for her project and her belief that the world will be a better place when we learn to “disagree curiously.”

Hoffer, who is Jewish and involved in the Jewish campus organization Hillel, said the club made an effort to reach out to fellow students in the days after the Oct. 7 terrorist attack by Hamas.

Her original message to her Lowell House listserv invited recipients to text or email her or meet up for a coffee. The email mentioned her work with Harvard’s Intellectual Vitality committee — an initiative that looks to improve dialogue on diverse perspectives across campus, and her academic work learning about the conflict.

“I was just flooded with messages from people I had never heard of, I’ve never met. Somebody who was an alum of the House I didn’t even know was on the listserv, wanting to talk about this and saying, ‘Thank you for not judging. This is such a difficult time to have a conversation,’” Hoffer said. “The first question I received was, ‘What’s the best solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?’ Which I still haven’t answered.”

That first question, Hoffer said, made her think to set up a Google Voice number and answer some questions every so often. And from there it exploded. The organization now has 27 volunteers from five different countries, different religious, political, and socio-economic backgrounds and who range in age from 19 to 79.

“They’ll apply and answer a series of questions, the most important of which is to say: ‘This is a really difficult issue. How do you anticipate sharing information that you disagree with?’” Hoffer said. “And if they answer that question poorly, that’s fine, not the organization for them. Our mission as a hotline is not to take a side or endorse a position. It’s not to say this or that is the answer. It’s founded on a very basic premise, which is to say to be part of a conversation, you should know what your interlocutors are saying.”

“Our purpose is to share as many perspectives as we can, and ultimately, we don’t care what position the person who asks the question takes. We just care that it’s a position that’s founded in some sort of knowledge base.”

Shira Hoffer ’25

In Monday’s talk, Hoffer recalled a volunteer from Iran.

“He did not believe in the legitimacy of the State of Israel whatsoever. And he volunteered alongside some of our volunteers who live in Israel and consider themselves staunch Zionists,” she said. “All of these volunteers were united by the belief that education is important, and information is important.”

To answer users’ questions, volunteers send links to resources, sometimes with differing perspectives on the same issue, and encourage follow-up questions.

“That is to say, if somebody asks how much of Gaza’s water supply does Israel have control over? We can answer that question with a number. Sometimes it is actually a bit more complicated than that,” Hoffer said. “Our purpose is to share as many perspectives as we can, and ultimately, we don’t care what position the person who asks the question takes. We just care that it’s a position that’s founded in some sort of knowledge base.”

The hotline has a disclaimer on their website. “Volunteers may send a few op-eds or social media threads to give the user a sense of what is out there, but that does not mean the volunteer is endorsing those views, implicitly claiming that they are factually correct, or equating the morality of different narratives.”

Hoffer said Monday that this aspect is key.

“Sometimes we’ll say, ‘This is the majority opinion, and this is the minority opinion,’ if it’s very clear, but otherwise, we’ll be explicit and say, ‘Here are a range of opinions, but they’re not all equal,’” she said. “That’s really important to us.”

Volunteers are sometimes confronted with hate speech and are trained not to tolerate it in any form on the hotline.

“If they then demonstrate to us that they’re just trying to start a fight, then we will say, ‘The purpose of this hotline is to be informational. We’re here to share different resources. We’re not here to engage in an argument,”’ she said.

But sometimes, what seems like prejudice is really ignorance.

“Somebody could say something that looks like they could be trying to start a fight, or they could know very little about the topic, only using words that they’ve heard and really be asking a genuine question. Our policy when it’s unclear is to say, ‘Thank you very much for reaching out, and if I understand your question correctly …’ and then maybe rephrase it in a less charged way,” Hoffer adds. “People really do have genuine questions in the world.”

The Hotline is a project of the Institute for Multipartisan Education, also run by Hoffer. It aims to promote constructive disagreement in educational institutions, and its slogan is “disagree curiously.”

“We lean into curiosity as a tool of change,” Hoffer said. “Curiosity reduces polarization and makes people more willing to hear perspectives that they disagree with.”