John Moore/Getty Images

Treat addiction with psychedelics?

Despite promise of success stories from patients in recovery, Law School panel cautions that research is lacking on benefits vs. risks

Mark Guckel had struggled with crack addiction since high school. Despite numerous attempts to overcome his substance use disorder, nothing helped. That is, until he tried psychedelic plants, such as ayahuasca, psilocybin, and ibogaine. The experience changed his life. Now a professional recovery coach, Guckel said psychedelics might hold a promise to treat addiction disorders.

Guckel shared his story of addiction and recovery during an online panel sponsored by the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School on Tuesday afternoon, “New Ideas for Substance Use Condition Treatment: Could Psychedelics Help?” But he warned that psychedelics is just one of many other treatments for substance-use disorders. Psilocybin and ibogaine are federally illegal in the U.S., with some exceptions for medical research.

“I can say that while psychedelics helped me to stop using substances, I’d like to reflect that these aren’t a cure,” said Guckel, a founder of a company that offers psychedelic-assisted recovery. “They are catalysts. They’re sacraments, they’re medicines, they’re tools. They’re one of many pathways. There are many other treatment modalities that are out there, from regular treatment to medication-assisted recovery to other holistic modalities that can help us live better lives.”

17% Of Americans over the past year have struggled with substance use disorder yet only 10% have accessed treatment

Accounts like Guckel’s and the idea that psychedelics might prompt a neurochemical reset in the brain have many looking to the approach as a promising treatment for addiction disorders. Around 17 percent of Americans have met criteria for a substance use disorder in the past year, said Stephanie Tabashneck, the event’s moderator. Yet fewer than 10 percent get treatment, she said.

“We have a treatment shortage. We also know that a lot of the treatments that we have are not particularly effective,” said Tabashneck, senior fellow of law and applied neuroscience, a collaboration between the Center for Law, Brain & Behavior and the Petrie-Flom Center.

After reminding the audience that none of the information shared in the panel should be considered legal or medical advice, Tabashneck offered a word of caution about psychedelics.

“Psychedelic therapy is not a replacement for medication treatments, like methadone for opioid-use disorder. All of our panelists will also agree that these are not first-line treatments. If someone has a substance-use disorder and it’s early, no one is recommending or suggesting that you should go ahead and try the psychedelics first as a method of treatment.”

Conventional treatments for addiction include behavioral therapies, such as contingency management and medication compliance therapy. There are also medication-assisted recovery treatments for opioid, alcohol, cocaine, and cannabis-use disorders. But the enthusiasm for psilocybin and ibogaine for treating substance-use conditions has been gradually increasing.

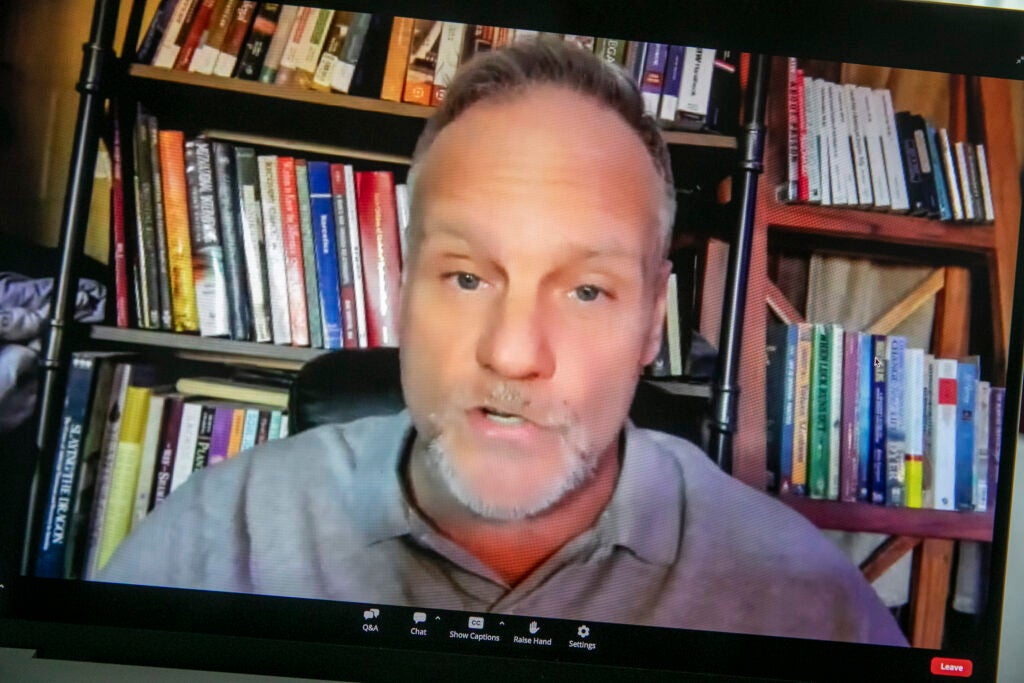

Panelist Mark Guckel describes how psychedelics helped him overcome an addiction to crack.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Panelist Mason Marks, visiting professor of law, Harvard Law School, and senior fellow and lead of the Project on Psychedelics Law and Regulation at Petrie-Flom, highlighted the legal and medical concerns about psilocybin, also known as magic mushrooms, and ibogaine, a psychoactive substance found in iboga, a shrub that’s native to Central West Africa.

“Unlike psilocybin, there’s no clinical ibogaine research in the U.S. right now, and that’s likely due in part to the risk of cardiovascular adverse events,” said Marks. “Ibogaine has been linked to heart attacks and some deaths.”

Marks said there are efforts in some cities and states across the U.S. to decriminalize psilocybin. Last year, Oregon opened a state-regulated program for supervised administration of psilocybin, and next year, Colorado will open a similar program for psilocybin and possibly ibogaine to be used as a treatment for addiction under medical supervision, he said. But it won’t be without concerns.

“In light of the federal illegality of psilocybin and ibogaine, there are many unresolved legal questions, some challenging legal questions and questions of potential liability, as well for licensed healthcare professionals who choose to get involved in these programs,” Marks said.

Neuroscientist Deborah Mash, professor of neurology and molecular and cellular pharmacology, Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine, has been studying the effects of ibogaine in substance-use disorders for more than three decades. She warned that it is not for everyone.

“I saw patients exhibit a remarkable recovery for a longstanding heroin abuse, cocaine-dependency disorder, including a young man who was on methadone maintenance who remarkably had no withdrawals, no cravings, and put their desire to go out and get and use drugs in remission,” said Mash, also the director of the Brain Endowment Bank at the University of Miami and chief executive officer and founder of DemeRx. “It’s a very powerful addiction interrupter.”

And yet, for people who may have an underlying psychiatric comorbidity like schizophrenia or a bipolar disorder diagnosis, psychedelics might pose a serious health risk, said Mash. She also warned against self-medication with psychedelics obtained through online distributors. “We want these molecules to be used in a medical way by qualified clinicians and therapists who understand these types of therapies and how they can work best.”

Despite all the craze around psychedelics, little research has been done to prove their efficacy treating addiction disorders. Mash pleaded for more evidence-based research that could lead to regulatory approval and make such treatments safely available to those who are “suffering the most.” So far, what researchers have is anecdotal. “And we know that data are not the plural of anecdote,” she said.