Why are we so divided? Zero-sum thinking is part of it.

Researchers examine who embraces mindset that one’s gain is another’s loss, and how that affects our politics — in sometimes surprising ways

A recent working paper charts the surprising politics of zero-sum thinking — or the belief that one individual or group’s gain is another’s loss — with a goal of offering fresh insight into our nation’s schisms.

The buzzworthy paper was co-authored by Stefanie Stantcheva, the Nathaniel Ropes Professor of Political Economy and founding director of Harvard’s Social Economics Lab. Its analysis drew from detailed surveys of more than 20,000 Americans. This allowed Stantcheva and her co-authors to measure the trait’s prevalence across demographics and party identities while also correlating zero-sum thinking with family histories and policy views.

It turns out zero-sum thinking does not map neatly with party affiliation.

“But it certainly helps explain variations in people of the same political leaning,” Stantcheva said.

For instance, the mindset is linked with support for redistributive policies, such as progressive taxation, universal healthcare, and affirmative action. Then again, it predicts a restrictive stance on immigration. On average, Democrats proved slightly more zero-sum than Republicans, with a greater tendency to view government as having a role in balancing inequities. But left-leaning voters with the strongest zero-sum tendencies also disproportionately split for Donald Trump in the past two presidential elections.

Zero-sum thinking by political party

Vertical lines show the mean zero-sum index for each political party. “Republican” includes respondents who considered themselves “Strong Republican” or “Moderate Republican”, and “Democrat” includes respondents who considered themselves “Strong Democrat” or “Moderate Democrat.” Those who considered themselves “Independent” are not shown.

Source: “Zero-Sum Thinking and the Roots of U.S. Political Divides”

Some of the 21st century’s most perplexing voter behavior makes a lot more sense when viewed through the prism of zero-sum thinking. “It helps rationalize why certain groups who stand to gain economically from government redistribution — white, rural, and older populations — tend to oppose government redistribution, while those who stand to lose — urban and younger populations — tend to support it,” the co-authors wrote.

Informing the economics researchers’ approach was a rich body of previous research — including by anthropologist George Foster, the first to hypothesize in the 1960s that certain societies hold an “image of limited good,” with a firm belief in the finite nature of wealth and other resources.

“He was studying zero-sum thinking in rural Mexico,” said co-author Sahil Chinoy, a Ph.D. student in economics at the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School and former graphics editor for The New York Times. “What we’re doing is bringing the concept to modern American politics and policy, and seeing what it helps us explain.”

Study co-author Sahil Chinoy.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The research team designed their survey in three blocks. The first sought to gauge the mindset’s frequency in several domains, including race relations, immigration policy, international trade, and rich vs. poor. “You might think people have varied views in different situations,” Stantcheva explained. “What we were interested in here was the general tendency to think in zero-sum terms.”

The second set of questions explored the implications of zero-sum thinking on policy views. “The general finding is that if you think some groups become better off at the expense of others, you’re much more likely to want the government to step in and correct that,” Stantcheva said.

A third set concerned the respondents’ ancestral ties, with questions designed to capture the childhood circumstances of parents and even grandparents. “This allowed us to reconstruct a very detailed family history, which turns out to be key to seeing what shapes zero-sum thinking,” Stantcheva said.

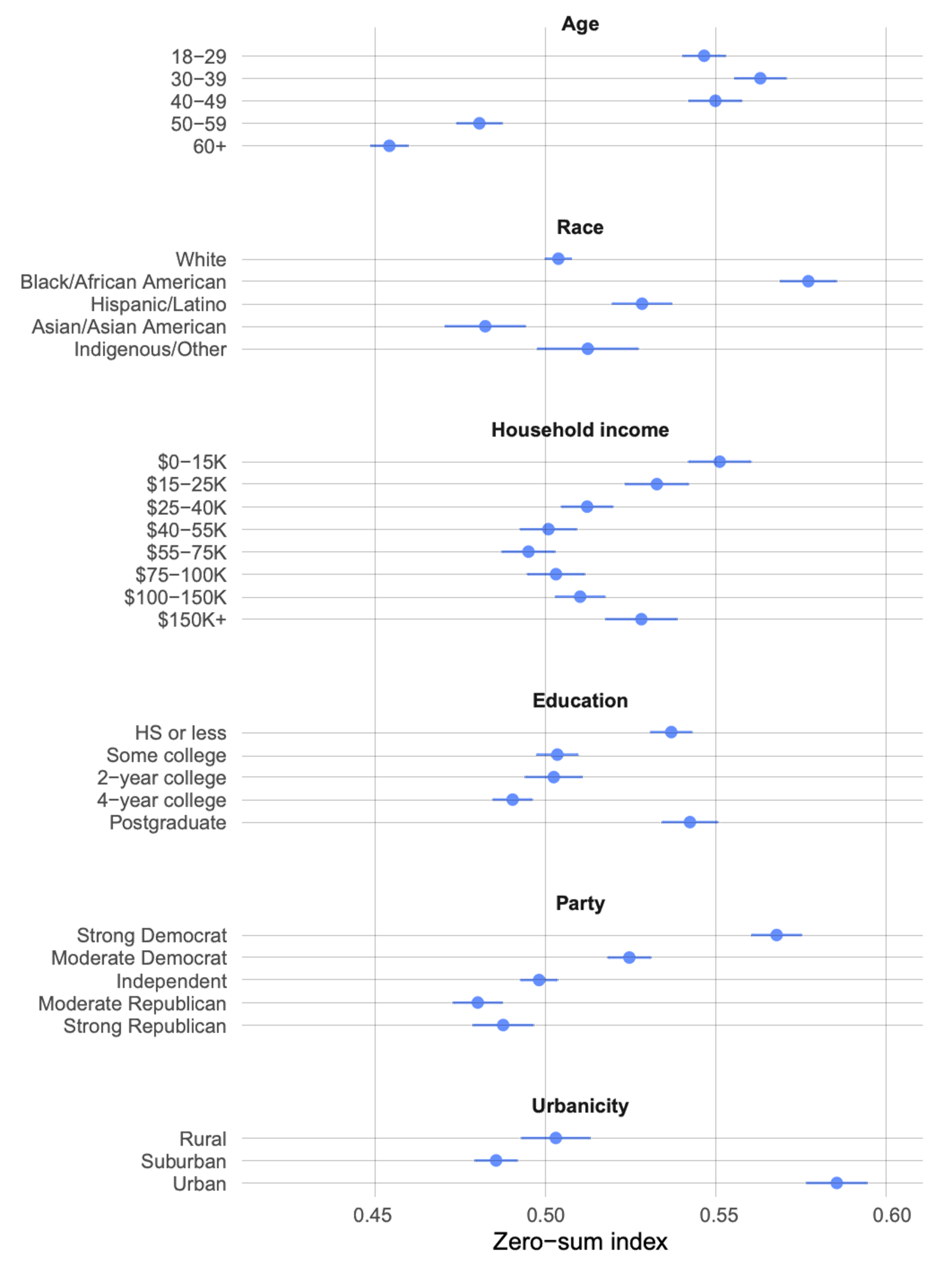

Zero-sum thinking by demographic group

The researchers specifically investigated experiences with what Stantcheva called “three core parts of U.S. history”: enslavement, immigration, and whether the respondent’s family ever achieved the American Dream.

A recent family history of immigration is associated with being less zero-sum. Same goes for those who simply grew up with foreign-born neighbors. “Maybe your grandparents were in a place with a lot of immigrants who did very well,” Stantcheva said. “Your thinking today is likely to be less zero-sum.”

The opposite was true for those with a family history of enslavement, with the co-authors characterizing this social and economic arrangement as “inherently zero-sum” (or perhaps even “negative-sum”). The finding held not only for Black Americans with enslaved forebears. “We asked very broadly about enslavement experiences — for instance, people whose ancestors were victims of the Holocaust or the forced displacement of Native Americans,” Stantcheva said. “This history is very much associated with more zero-sum thinking today.”

The American Dream plays a more curious role, with middle-income respondents showing fewer zero-sum tendencies than high- and low-income groups alike. Early exposure to upward mobility appears to be key.

Zero-sum thinking and economic conditions

The black solid line is the percentage change in bottom 50 percent income for the first 20 years of an individual’s life while the blue dotted line is the average zero-sum index. Economic data are from the World Inequality Database.

Source: “Zero-Sum Thinking and the Roots of U.S. Political Divides”

One of the paper’s more stunning takeaways concerned the trait’s age-related patterns. “There’s a very stark figure in the paper that shows younger generations in the U.S. are significantly more zero-sum than older generations,” Stantcheva said.

Why would this be the case, the researchers wondered. A compelling explanation was found with information incorporated from the open-data World Values Survey, which poses a single question on zero-sum thinking in dozens of countries every five years. Detailed family histories were not available for these respondents. Instead, the co-authors used the ups and downs of Gross Domestic Product in each country sampled.

“If there’s been more growth, more mobility in the first 20 years of your life, we find it’s associated with being significantly less zero-sum,” Stantcheva summarized. “So in places like the U.S. or Continental Europe, where things used to be better in terms of mobility, the older generations are a lot less zero-sum.”