To assess a smoker’s lung cancer risk, think years — not packs

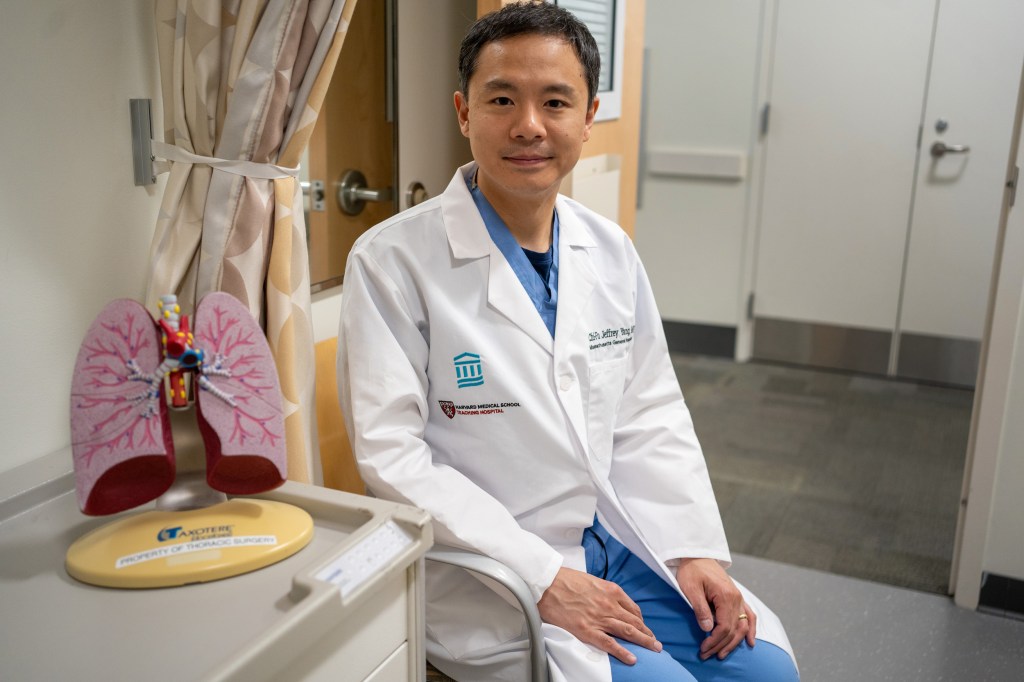

Jeffrey Yang with patient Albertha Gethers, who was treated for lung cancer at Mass General Hospital.

Photos by Jodi Hilton; Illustrations by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Far more cases get caught when screening guidelines consider duration of habit regardless of intensity, study finds — especially among Black patients

When deciding who to screen for America’s deadliest cancer, should a person who has smoked a pack a day for 20 years get priority over someone who has smoked fewer cigarettes over the same amount of time?

That’s the question tackled by Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital researchers in a recent study that showed that lung cancer screening guidelines set by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force — requiring the equivalent of a pack a day for 20 years — miss a large proportion of cases and fail to close a screening gap between Black and white patients. That gap means lung cancer among Black patients is too often caught later in the disease’s course, leading to higher mortality.

The researchers, whose work was published earlier this year in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, suggest switching instead to a simple measure that would recommend annual screening for anyone who’s smoked for 20 years, regardless of how many cigarettes they smoke a day. Both guidelines also require the individuals be between ages 50 and 80 and either be current smokers or having quit within the last 15 years. The simplified guideline would widen the pool of those who qualify for lung cancer screening and, according to the study, both increase the proportion of cancer cases that are caught and virtually eliminate racial disparities in lung cancer screening eligibility.

“We found that it completely eliminated the racial disparity in the proportion of lung cancer patients who would have qualified among both people who currently smoke as well as people who formerly smoked,” said Alexandra Potter, the study’s first author, clinical research coordinator at Massachusetts General Hospital, and president of the American Lung Cancer Screening Initiative.

Smoking duration vs. intensity and risk

The 20 pack-year threshold can be difficult to use and inaccurate, said senior author Chi-Fu Jeffrey Yang, associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and a thoracic surgeon at MGH. That’s because the equivalent of smoking a pack a day for 20 years could mean smoking half a pack daily for 40 years, two packs a day for 10, or any other permutation that results in the required combination of smoking intensity and duration. In addition, most people who smoke have smoked different amounts at different times of their lives which, decades later, can be difficult to recall. Plus, while it may make intuitive sense that someone who smokes more intensely has a higher risk of developing lung cancer, studies have not shown that the risk due to smoking intensity is equivalent to the risk from smoking duration, as the pack-year standard implies, the authors said.

White patients tend to smoke more each day

In the work, supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, researchers applied both the current screening guidelines and the proposed simplified guidelines to participants in two studies: the Southern Community Cohort Study, which included both Black and white subjects receiving care at community health centers in the U.S. Southeast, and the Black Women’s Health Study, whose study population was limited to Black women. Both included data on subjects’ health and smoking history.

Researchers first applied the current screening guideline and found that, of those who developed lung cancer in the Southern Community Cohort Study, just 58 percent of Black patients and 74 percent of white patients would have qualified for screening. In the Black Women’s Health Study, just 43 percent of those who developed lung cancer would have qualified for screening.

By contrast, applying the simplified 20-year smoking duration guideline would capture over 80 percent of both Black and white participants who developed lung cancer in the Southern Community Cohort Study, and 64 percent of lung cancer patients in the Black Women’s Health Study. That would not only significantly increase the percentage of lung cancer cases eligible for screening, it would virtually eliminate the racial disparity in eligibility.

That racial disparity, the authors said, largely stems from the fact that current guidelines include the pack-a-day measure of smoking intensity, which varies between Black and white individuals. White individuals smoke significantly more each day, lowering the bar for screening eligibility. That has been seen in previous studies and was apparent in Potter and Yang’s research as well. Research has identified several possible explanations for differences in smoking intensity and lung cancer risk, including differences in nicotine metabolism between Black and white people who smoke. However, there are also an array of social and cultural factors still unexplored, the authors said.

“We showed that the median number of cigarettes smoked among Black patients with lung cancer was almost half of that among white patients with lung cancer,” Potter said. “Even though they smoke similar durations, intensity was really the driving factor in the difference between them.”

Other screening barriers

The debate over who should get screened and when is just one part of lung cancer’s dismal landscape. Smoking is its leading cause, accounting for 85 percent of cases. It is one of the most aggressive cancers, Yang said, meaning it can spread rapidly if not caught early. It kills more people annually — in both the U.S. and the world — than colon, breast, and prostate cancers combined, and is expected to kill 125,070 Americans in 2024, according to statistics from the American Cancer Society.

Despite lung cancer’s deadly record, a recent study by the American Lung Association showed that more than 80 percent of those who qualify for screening don’t even know it is an option. Further, only between 5 percent and 19 percent of those who qualify actually get screened for lung cancer.

“It pales in comparison to breast cancer, colon cancer, and cervical cancer screening, where 70 to 80 percent get screened,” Yang said. “There’s a huge gap.”

In addition to lack of awareness, part of that gap may be due to additional requirements placed on those seeking a lung cancer screening, Potter said. Unlike a mammogram, which a patient can schedule themselves, lung cancer screening has to be scheduled in conjunction with a visit to a healthcare provider. While it’s not bad to have a provider involved, Potter said, it is an extra step and one required by many insurers before they’ll pay for the procedure.

“Out of lung, breast, colon, and cervical cancer, lung cancer is the only one where it’s required to have this formal documentation of a shared decision-making visit,” Potter said.

The screening itself is straightforward, noninvasive, and takes just minutes, Yang said. Patients can stay in their street clothes and lie on a table for a CT scan that takes a series of X-rays to create an image of the lungs, revealing any tumors that might be present.

Yang said a recent patient’s case highlights the situation. She smoked lightly — just three cigarettes a day — but for many years. The light intensity of her habit put her at just 8.4 pack-years, not enough to qualify for lung cancer screening. Fortunately, she was able to get screened through an ongoing clinical trial, called INSPIRE, that Potter and Yang are leading to investigate lung cancer screening in high-risk Black women. The scan showed three small, aggressive cancerous nodules that Yang was able to remove surgically.

“She’s doing very well right now, but she’s 69 and without the screening this would certainly have come back in her 70s as stage IV lung cancer with a very, very different outcome,” Yang said. “We’re hoping that people take a good look at pack-years and whether this is really the best measure overall and the best criterion for Black cancer screening eligibility.”