How to apply cool-headed reason to red-hot topics

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

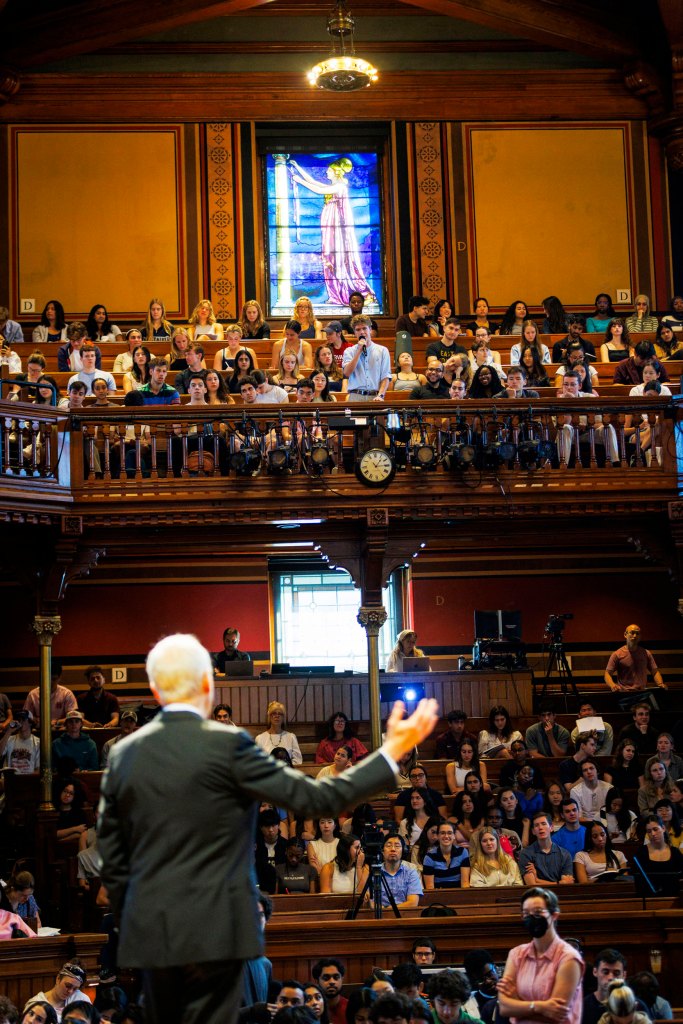

Michael J. Sandel brings back wildly popular ‘Justice’ course amid time of strained discourse on college campuses

Which is better? The 1996 film adaptation of “Hamlet” starring Kenneth Branagh or a spoof on the Prince of Denmark’s “to be or not to be” soliloquy delivered by Homer Simpson?

The question was posed last month to more than 800 undergraduates during “Justice: Ethical Reasoning in Polarized Times.” The legendary Gen Ed offering has returned to Sanders Theatre this semester after more than a decade of availability only as a prerecorded offering online. Originally launched in 1980, the course became wildly popular for its format: guided student debate of the hottest issues of the day, informed by study of classic theories on moral decision-making.

“The first thing I want to know is which one you like most,” announced “Justice” creator Michael J. Sandel, the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government. Most in the room, dismissing the third option of a WWE body-slam clip, lavished applause on “The Simpsons.”

But the conversation turned spiky on a second point: “Can we derive what’s higher, what’s worthier, what’s nobler, from what we like most?” Sandel asked. “Or is there a gap between the two?”

One student stuck with “The Simpsons,” arguing that it was the most pleasurable. Another noted the cartoon excerpt owed its existence to Shakespeare’s worthier source material. Still others characterized the TV show as fleeting pleasure versus the intellectual and even spiritual nourishment of high art.

From the stage, Sandel invited these divergent responses while pressing the room to consider new angles. “It’s an opportunity for students to dive into why they think the way they do,” observed Darlene Uzoigwe ’25, a government concentrator from Brooklyn.

Generations of Harvard graduates, including U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson ’92, J.D. ’96, and former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Preet Bharara ’90, have cited the impact the course had on their careers and lives. In 2009, a recorded version went on to become the first Harvard course freely available online.

“It was an experiment in using new technology to open access to the Harvard classroom,” Sandel said in an interview last month. “We never dreamt that tens of millions of people around the world would want to watch lectures on philosophy.” More than 38 million have viewed the course on YouTube, and millions more on foreign language web platforms.

The in-person offering was paused when the political philosopher noticed first-years enrolling despite having watched “Justice” in high school. “I tried for a couple of years to change some of the examples, stories, even the jokes,” Sandel said. “But I found I liked the original version and didn’t want to change everything. So, I decided to let it live online and teach other subjects.”

Most of these courses, including those on technology and globalization, were capped at 200 students. Trevor DePodesta kept trying to get a spot.

“It took me until now to get into one of his classes,” said DePodesta ’25, an Ethical Human-AI Interaction concentrator from San Diego. “I felt like the Harvard experience wouldn’t be complete until I sat in a lecture hall with him.”

As any alum of the course will know, the Homer-Hamlet matchup is really about exploring ideas about high and low pleasures outlined by 19th-century Utilitarian philosopher John Stuart Mill.

“I didn’t think you could discuss ‘Simpsons’ vs. ‘Hamlet’ for so long,” said Saskia Hermann ’28, a first-year from Germany. “What I’ve learned so far is that you can always look at something twice — once from your initial point of view, and then you can apply a certain philosophical idea to look at it from that perspective.”

Also familiar to “Justice” veterans are course readings by Mill’s Utilitarian predecessor Jeremy Bentham as well as Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, and John Rawls. Bringing the class back to Sanders means Sandel has now updated the ethically charged issues that test the philosophers’ ideas.

The first weeks of the course, which carries, at times, the fizzy energy of a concert, covered readings and lectures on the philanthropic movement reportedly embraced by former cryptocurrency billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried, who was convicted this year on fraud charges. In one hypothetical, Sandel posed whether it was better to solve urgent medical needs in the developing world by becoming a physician or by making a lot of money in cryptocurrency and donating, say, $50 million to Doctors Without Borders.

“It’s a test of the Utilitarian philosophy underlying the Effective Altruism movement,” he explained.

Later, students will delve into climate change, artificial intelligence, and the polarizing consequences of social media. “From the time the course was first offered in the 1980s we’ve discussed affirmative action,” Sandel added. “Now we continue the discussion in light of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling against race-based affirmative action in university admissions.”

The real motivation for relaunching the course, Sandel said, was student feedback about the strained state of dialogue on campus. “It’s definitely true that there isn’t a lot of civil discourse going on,” said Maia Hoffenberg ’26, a linguistics concentrator from the Washington, D.C., area. “People have become entrenched in their own ideas.”

Sandel has been a supporter of other campus initiatives designed to boost civil discourse and intellectual vitality. Last winter he hosted a one-day session for faculty on cultivating healthy debate and another inviting students to grapple with the tangled ethics of artificial intelligence. At orientation this fall, Sandel offered a primer on engaging with highly disputed but important issues.

Hermann enjoyed the latter conversation so much she dropped a course to pick up “Justice.” “I really liked the way he asked questions and made us get to the point, rather than just lecturing on what he believes,” she said.

“I really liked the way he asked questions and made us get to the point, rather than just lecturing on what he believes.”

Saskia Hermann

Others taking “Justice” have been reading Sandel since high school — and clearly consider themselves fans.

“Yeah, that’s my boy!” called out one student as Sandel appeared for a lecture last month.

After class, a handful of devotees line up near the podium clutching dog-eared copies of Sandel’s “Justice” (2009) or “The Tyranny of Merit” (2020). “I’ve been able to snag him after class a few times,” DePodesta shared. “He promised that if I come find him outside of class, he’ll sign my books.”

Offering such a large-scale course meant Sandel spent the summer recruiting, interviewing, and hiring an army of “Justice” teaching fellows. A staff of 32 graduate students this fall helms a total of 64 sections, with many scheduled in the early evening at first-year dorms and various Harvard Houses. The goal is to “carry the learning beyond Sanders Theatre,” said Sandel, who won’t teach the course next fall due to a planned sabbatical.

That encourages students to continue conversations about immigration, abortion, reparations, and extreme wealth — to name a few topics — over dinner. “My roommates and I have these intense debates after every single class,” shared Leverett House resident Hoffenberg. “We get mad at each other, but it’s all very lively and very academic. It’s honestly been one of the best things about taking the class.”