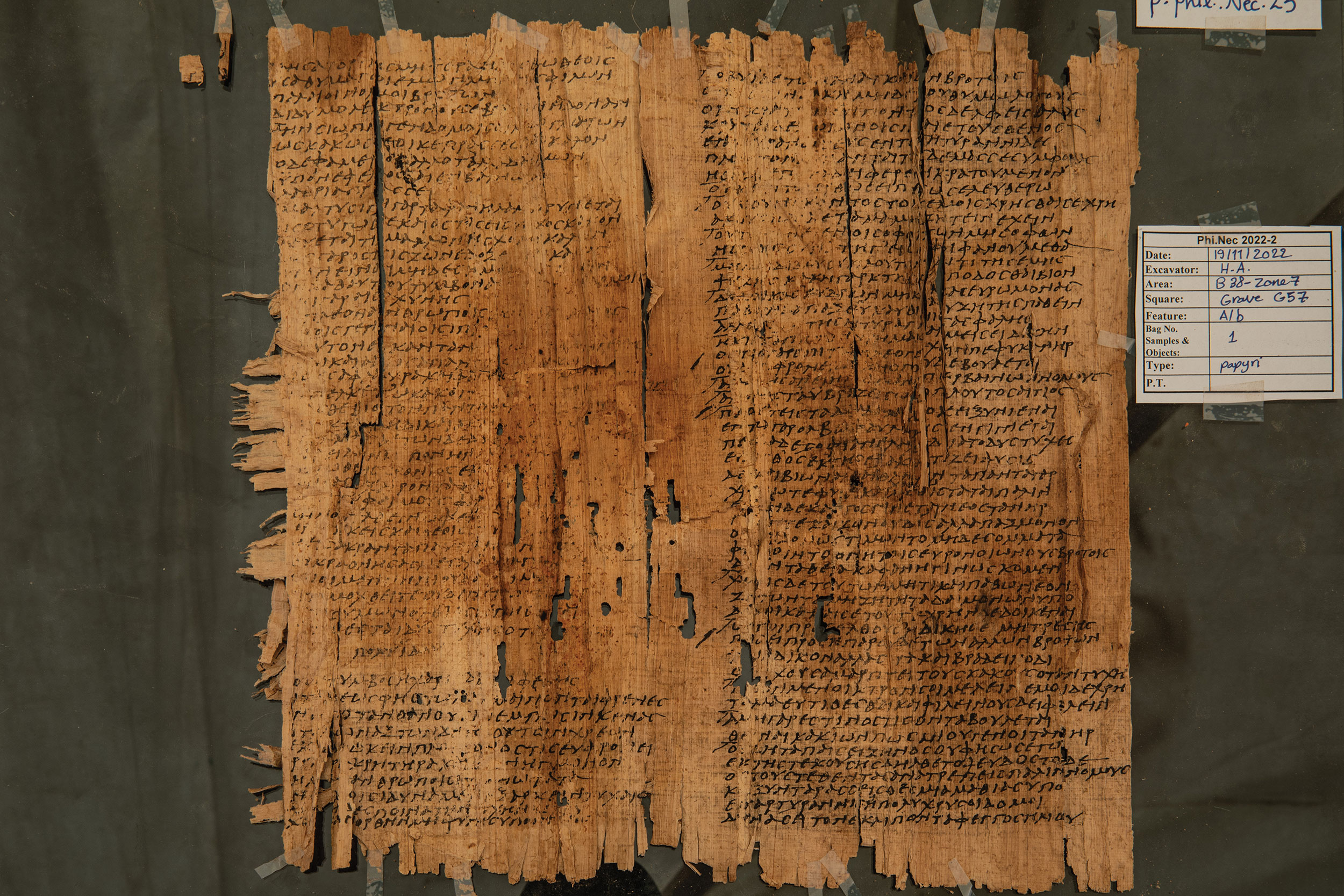

Inscribed with fragments of Euripides’ plays, the papyrus was found at the ancient necropolis in Egypt.

Photo courtesy of Yvona Trnka-Amrhein

Unearthed papyrus contains lost scenes from Euripides’ plays

Alums help identify, decipher ‘one of the most significant new finds in Greek literature in this century’

For centuries, questions have loomed about two of Euripides’ lesser-known tragedies, “Ino” and “Polyidus,” with only a smattering of text fragments and plot summaries available to offer glimpses into their narratives.

Now, in a groundbreaking find, two Harvard alumni have identified and worked to decipher 97 lines from these plays on a papyrus from the third century A.D.

Yvona Trnka-Amrhein ’06, Ph.D. ’13, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, was the first to identify part of the text as an excerpt from “Polyidus,” a scene in which King Minos of Crete confronts a seer, demanding he resurrect his son. Trnka-Amrhein and colleague John Gibert, Ph.D. ’91, identified the remaining text as lines from “Ino,” a scene that probably depicts the title character boasting victoriously after orchestrating the deaths of her stepchildren. Their research was published this month in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, or the Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy.

The papyrus as it was uncovered at the ancient necropolis.

Photo courtesy of Yvona Trnka-Amrhein

The papyrus was discovered in 2022 in a burial shaft at the ancient necropolis of Philadelphia, Egypt, by a team from the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities. In June, Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies hosted a conference with Trnka-Amrhein, Gibert, excavation team leader Basem Gehad, and 12 other scholars from around the world to compare research, including Harvard Professor of the Classics Naomi Weiss. Classics Ph.D. candidate Sarah Gonzalez also participated.

“It’s arguably one of the most significant new finds in Greek literature in this century,” Weiss said. “I don’t expect there to be another find like this in my lifetime, in my particular field of expertise. For Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies to host the first public investigation into this material was really exciting.”

Weiss, whose research focuses on ancient Greek performance culture, especially classical Greek drama, discussed the significance of the finding. The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me about your experience at the New Euripides Conference?

That was a once-in-a-lifetime experience for a scholar of Greek tragedy. To be one of 15 scholars worldwide who got to see this stuff for the first time was really incredible. There was a core group of people there who were literally going through the fragments word by word and discussing whether Yvona and John’s readings of each part of the papyrus were correct. Some of it is hard to read, so individual words are contested.

What are your early takeaways from the new fragment of “Polyidus”?

It quite clearly seems to be a dialogue between King Minos of Crete and Polyidus the seer, where Polyidus is saying, “It’s wrong to demand that I revive your son from the dead, that goes against all laws of nature,” and Minos is basically saying, “Well, I’m king and what a tyrant asks for has to happen.” The passage seems to be really concerned with questions of tyranny and the extent of human power and free will, and how those can jostle against each other. How far can human power go, how far can human knowledge and skill extend? Even to the point of reviving someone from the dead? The fact that Polyidus does end up reviving the dead son is an example of how Euripides liked to play with plot twists and “happily ever after” endings. At the same time, he was deeply engaged with contemporary intellectual questions.

“These fragments are unusual because they’re relatively long and give us a lot of information about plays that we previously knew less about. ”

Naomi Weiss

Naomi Weiss.

Photo by Jodi Hilton

And the new fragment of “Ino”?

If the editors’ reconstruction is correct, then “Ino” is the only surviving fragment that has a dialogue between the two wives: Ino, the king’s first wife who was long presumed missing and has returned in disguise; and Themisto, the second wife. Each wife has two children. Themisto tries to kill Ino’s, but Ino tricks her into killing her own instead. Themisto commits suicide and then the king mistakenly kills one of his sons by Ino, and she walks into the sea with the other. In this excerpt, the meeting of the two wives brings to the fore the doubleness and repetition running throughout the play and it in turn makes us better appreciate quite how excessive this tragedy was, with multiple wives, multiple children, multiple deaths, multiple suicides.

Does this change anything about our understanding of Euripides?

“Ino” is a really gruesome tragedy. The only person left at the end is the king, and he’s lost all his wives and all his children. This seems like tragedy on steroids. It’s the sort of experimentation with how far you can push a tragic plot that may remind us of later plays of Euripides. “Ino” may well be a significantly earlier play — there seems to be a reference to it in a comedy by Aristophanes that was produced in 425 B.C. If that is a reference to “Ino,” we know the tragedy was performed before this date. We tend to think of Euripides’ super experimental plays as being from the last decade of his career, where he’s just going all out and questioning the very form of tragedy. If we are right in dating this earlier, then that changes our understanding of how tragedy developed through the fifth century.

Who might have written the excerpts on this papyrus, and why?

We don’t know. It’s a really open question. At the conference, one of the questions that kept coming up was, is it significant that these two plays, which have something to do with the death of children, were found in a pit grave where there were buried — at different times — the body of an older woman and the body of a child? But it’s very hard to make any reliable conjectures about that connection. Some people at the conference thought that these extracts may be part of what’s called the “anthology tradition”: Maybe someone was teaching Euripides’ plays or hoping to draw from them in their own compositions and compiled a set of useful passages from each tragedy. Another scholar at the conference thought that maybe these were written out to be part of a performance, essentially like a script for actors. All of these questions remain and will be debated.

How much do we know about Euripides’ work as a whole?

When we think of Greek tragedy, we tend to think of the “big three”: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, who all wrote tragedies in the fifth century B.C. Of these three tragedians, we have much more surviving of Euripides. While we have seven full plays by Aeschylus and Sophocles, for Euripides, we have 19 full plays and 18 of those can reliably be said to be his. Then we have a lot of fragments. The fragments of plays are preserved across different media — a lot of them are quotations that come up in other authors, but we also have papyri. This is the latest find of tragedy on papyri. These fragments are unusual because they’re relatively long and give us a lot of information about plays that we previously knew less about.