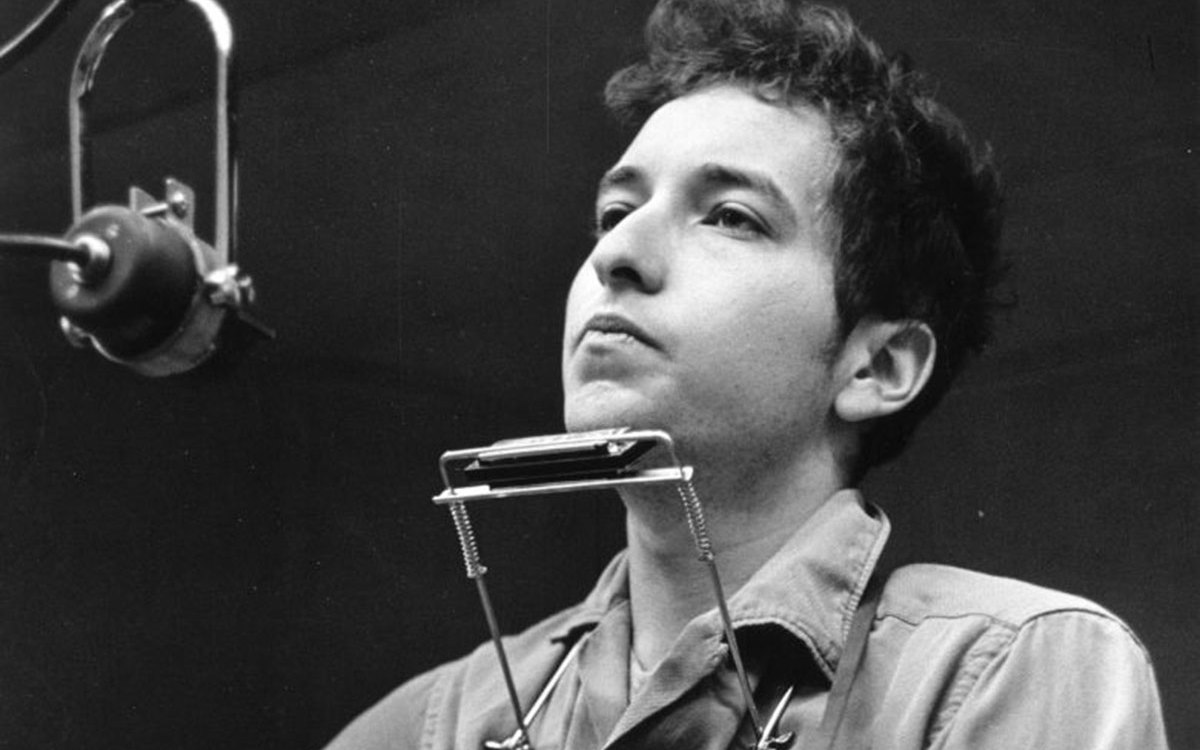

James Wood (left) and Laila Lalami.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

How a ‘guest’ in English language channels ‘outsider’ perspective into fiction

Laila Lalami talks about multilingualism, inspirations of everyday life, and why she starts a story in the middle

Laila Lalami reached for her phone early one morning and found a baffling notification. If she were to leave her house right then, it said, she could make it to YogaWorks by 7:30 a.m.

The award-winning novelist did not immediately leave for yoga class. Instead, she spent the day pondering technology and its access to people’s unexpressed thoughts and unrealized actions. The experience, now more than 10 years in the past, left her with the idea for her forthcoming novel.

“I turned to my husband, and I said, ‘Pretty soon, the only privacy we’re going to have is in our dreams,’” Lalami recalled at a recent Writers Speak event hosted by the Mahindra Humanities Center. “Then I thought, ‘What if someday even that boundary starts to become porous? What might happen?’”

Lalami, author of “The Moor’s Account” (2014) and “The Other Americans” (2019), read an excerpt from “The Dream Hotel,” available in March. Moderator James Wood, professor of the practice of literary criticism, also asked her about multilingualism, narrative structure, and finding inspiration in everyday life.

Even after publishing four novels, Lalami — the 2023-2024 Catherine A. and Mary C. Gellert Fellow at Harvard Radcliffe Institute — said she still describes herself as a “guest” in the English language.

The trilingual author grew up speaking both Arabic and French in post-colonial Morocco. Enrolled at a French primary school, her introduction to the written word came via French children’s classics like “Tintin” and “Asterix.” As an English major at Université Mohammed-V in Rabat, Lalami began to resent how early French education had prevented her from developing that initial literary connection to Arabic.

“I developed a dislike of writing in French,” Lalami said. “I felt that the more I did it, the more I felt awkward doing it. It felt to me there was a bizarre sort of colonial gaze that I could not detach from the writing.”

Now working in English, Lalami still feels a sense of estrangement from the language. But she’s able to channel it into her creative process. As a writer, she sometimes imagines her dialogue is taking place in Arabic and she is translating it to English. This was particularly the case with her second novel, “Secret Son” (2009).

“If the story is successful, we forget to question things like what language they are speaking,” Lalami said.

As for narrative structure, Lalami spoke to the tendency of starting her books in the middle of a story, including multiple character perspectives and adding elaborate backstories.

She stumbled upon the approach “organically” with her first novel, “Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits” (2005), which opens with the capsizing of an inflatable boat carrying four Moroccans across the Strait of Gibraltar. From there, the narrative shifts between each of the characters, detailing their lives before and after the crossing.

“I started writing the story of this character as he’s going through this journey, and the story kept getting longer because I was doing these flashbacks about his life before he got onto that boat,” Lalami explained. “I thought, ‘Well, what happens to this other person that’s sitting next to him?’ So I decided to write a story about them.”

Similarly, “The Other Americans,” her fourth novel and a National Book Award finalist, begins with a car crash and unfolds through nine different first-person accounts. Wood, who is also a staff writer and book critic at The New Yorker, noted the rich details that bring the book’s immigrant characters to life — from the main character, a Moroccan man who names his California business “Aladdin’s Donuts,” to his wife’s confusion over an English sign that reads: “Don’t even think about parking here.”

“If we think of the fiction of immigration, it’s so centrally about varieties of estrangement, right?” Wood said. “It’s about trying to see things with new eyes.”

Lalami said she loves building characters’ backstories right down to the smallest detail. “As somebody who constantly feels as an outsider, I’ve come to realize that it’s very much the outsider-ness that makes me a writer,” she said. “That feeling of being on the outside looking in.”

The outsider perspective is what prompted Lalami to write “The Moor’s Account,” which won the American Book Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. The novel is the fictionalized memoir of Estevanico, an enslaved Moroccan on the ill-fated 1528 Narváez expedition to Florida. His name appears only in passing in historical records, inspiring Lalami to reconstruct his backstory before and after the expedition.

During the Q&A session, a student asked Lalami about the steps on her journey to becoming a writer, which included a linguistics Ph.D. program and a stint at a majority-male tech company.

Lalami responded with the same advice she gives to students in MFA programs: Every life experience can become material for fiction. Case in point? Her forthcoming novel features a female main character working at a large tech company.

“That is what helps you become a writer, is that feeling that you’re kind of weird and different from everybody,” Lalami said. “Don’t ever try to be like everybody else. Embrace that weirdness, because that’s what fiction comes out of.”