Can the U.S. regain the lead in the microchip race?

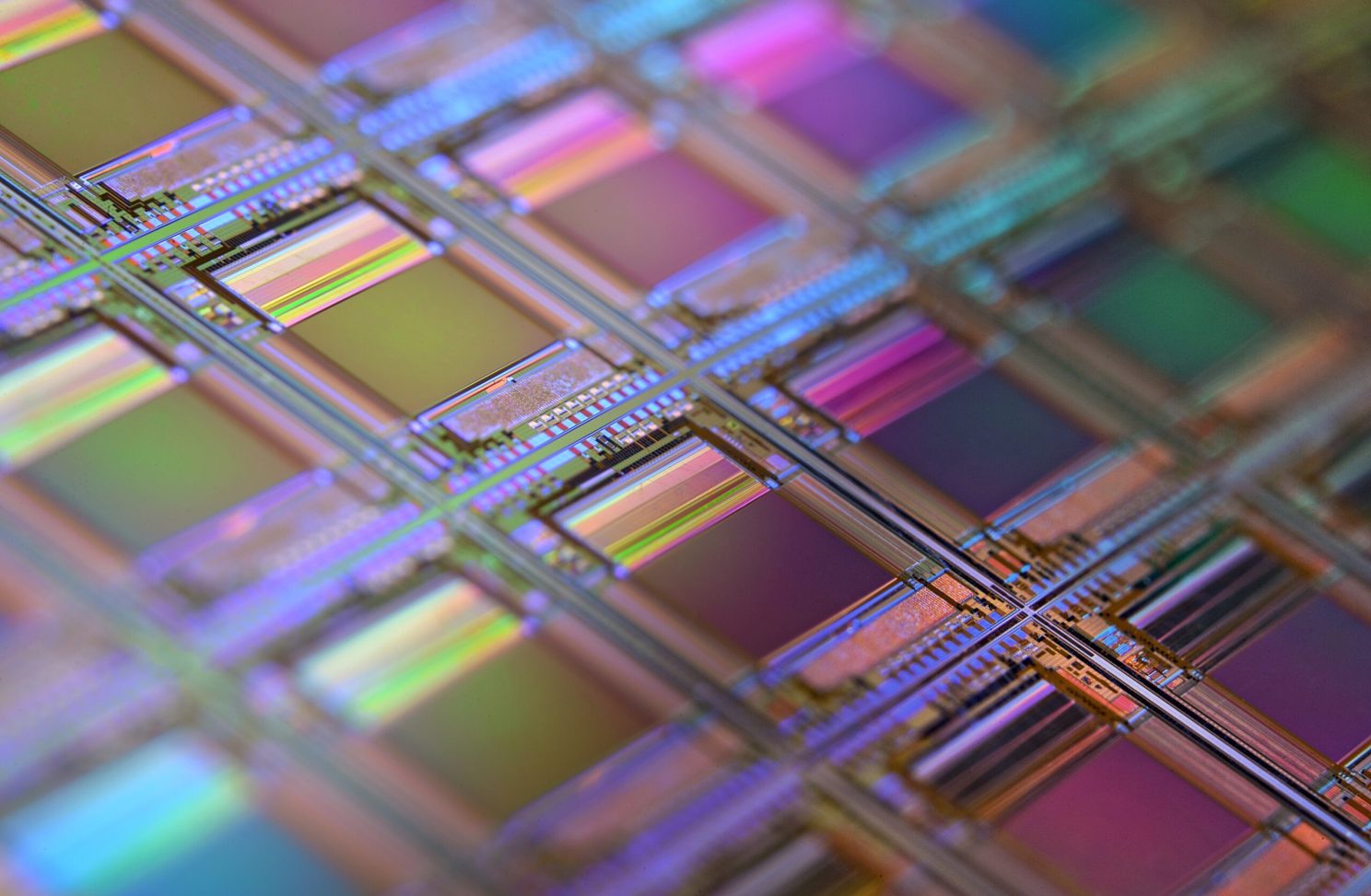

The CHIPS Act, with its $52 billion in subsidies, is a good start for incentivizing chip manufacturers to bring back to production to U.S. soil according to Jason Hsu, a research fellow at the Ash Center. Laura Ockel/Unsplash

Semiconductors, the building blocks of the modern information age, are critical components to seemingly every manufactured product from phones to cars to computers. To discuss the challenge of building new microchip manufacturing capacity, we sat down with Jason Hsu, a research fellow at the Kennedy School’s Ash Center and a former member of Taiwan’s parliament where he focused on technology policy and innovation.

ASH CENTER: How did Taiwan become the linchpin in global microchip production?

HSU: For the past three decades, Taiwan has been strategically developing the semiconductor industry as an important pillar of its national competitiveness strategy. Carrying out its industrial policy, which included investments in research and development — and recruiting U.S.-trained Taiwanese engineers and managers, Taiwan launched the Hsinchu Science Park in the 1980s, which ultimately developed into a powerhouse of chip manufacturing. Central to much of these efforts was Morris Chang, founding chairman of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC). Under Chang’s leadership, TSMC focuses relentlessly on the pursuit of engineering excellence and innovation in chip manufacturing. Today, Taiwan’s chip production accounts for 60 percent of the world’s total volume, and TSMC produces more than 90 percent of the leading-edge chips (defined as 7 nanometers and thinner). Hsinchu Science Park became a hub where up-and-down stream chip companies including those focused on design, manufacturing, equipment, testing and packing are tightly integrated.

ASH CENTER: President Biden is about to sign the CHIPS Act into law, which would pump an estimated $52 billion in subsidies to spur U.S. microchip production. How did the U.S. ultimately cede its leadership in global microchip production to Taiwan?

HSU: In 1968 Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore created Intel and shortly thereafter launched the world’s first microprocessor, establishing a decade-long leadership position in the semiconductor industry. The U.S. continued to maintain its leading edge in microchip manufacturing until a little over 20 years ago — outperforming Japan and the rest of world. However, after 2000, the U.S. shifted its focus to design, innovation, research and development — with a concomitant reduction in capital spending and outsourcing of chip manufacturing overseas.

ASH CENTER: The question of subsidies asides, what other challenges does the U.S. face to building up its domestic microchip manufacturing industry?

HSU: The CHIPS Act, with its $52 billion in subsidies, is a good start in paving the ground for incentivizing chip manufacturers to bring back to production to U.S. soil. However, compared to industry spending overall, the federal subsidies are relatively small. The truth is money alone isn’t enough. There needs to be a comprehensive strategy that aims at creating long-term sustainability and overall industry integration that encompasses immigration policy, STEM education, tax benefit and research and development.